Nonoperative

1. General considerations

Most proximal humerus fractures will heal without surgery, and many recover satisfactory function.

Outcome of nonoperative treatment depends upon the type of fracture, the degree of fragment displacement, and intrinsic fracture stability. Assessment of stability with image intensification is helpful according to the author’s experience.

Without fixation, displaced proximal humerus fractures are rarely improved with closed fracture reduction.

Nonoperative treatment should provide mechanical support until the patient is sufficiently comfortable to begin shoulder use, and the fracture is sufficiently consolidated that displacement is unlikely. The intrinsic stability provided by the periosteum may guide the type of immobilization.

In fractures of the greater tuberosity and/or the surgical neck, the fracture may rest in better reduction if the arm is immobilized in abduction with a cushion.

Once these goals have been achieved, rehabilitative exercises can begin to restore range of motion, followed by strength, and function.The three phases of nonoperative treatment are thus

- Immobilization

- Passive/assisted range of motion

- Progressive resistance exercises

Duration of Immobilization should be as short as possible, and as long as necessary. Typically, immobilization is recommended for 2-3 weeks, followed by gentle range of motion exercises. Resistance exercises can generally begin at 6 weeks. Isometric exercises may help maintain strength during the first 6 weeks.

2. Reduction of glenohumeral fracture dislocation

Proximal humeral fracture dislocations require prompt reduction of the glenohumeral joint dislocation.

Keep in mind that with fracture dislocations the need for conversion to an open reduction is highly likely. Preoperative plans should include this possibility.

Since the reduction of the dislocation may be difficult, regional or general anesthesia, including muscle relaxation, is recommended.

Note: Definitive operative treatment is usually best for glenohumeral fracture dislocations. Nonoperative treatment should be considered only if surgery has a significant risk, or if shoulder reduction has resulted in acceptable reduction of the fracture components.

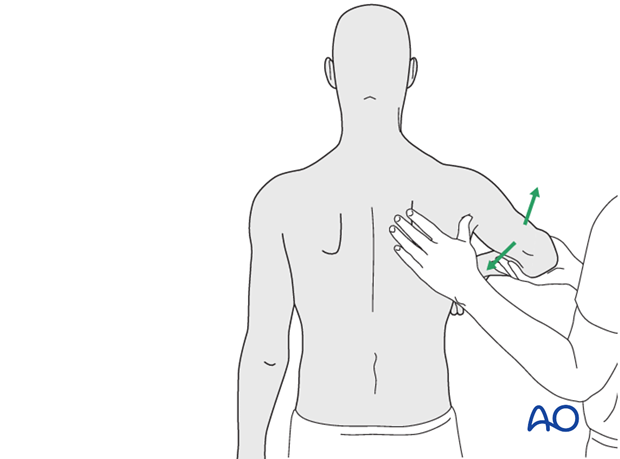

Principles of closed reduction (see illustration)

Axial traction on the arm is almost always helpful. Even with a fracture of the proximal humerus there is usually sufficient intact soft tissue so that the traction is transmitted to the humeral head.

Direct manipulation of the dislocated head segment can assist the reduction. Pressure should be applied over the prominent humeral head, and directed to push it back into the glenoid. Beware pressure on neurovascular structures.

Confirmation of glenohumeral reduction

Once the glenohumeral reduction is felt, it should be confirmed with true AP and axillary x-rays. Additional fractures or displacement should be looked for. When x-ray anatomy is not completely clear, a CT scan, often with reconstructed views, can be very helpful.

Check also the neurovascular status, especially distal pulses, motor function, and sensation. The axillary nerve is at particular risk and can be assessed by sensation over the lateral deltoid and the cooperative patient’s ability to contract the deltoid muscle.

Rule out rotator cuff tear

Particularly in older patients, glenohumeral dislocations may result in a torn rotator cuff. Early repair, before tendon retraction or significant atrophy, is the most effective treatment. If physical assessment does not confirm rotator cuff strength, additional studies (eg, ultrasound, MRI) should be performed promptly.

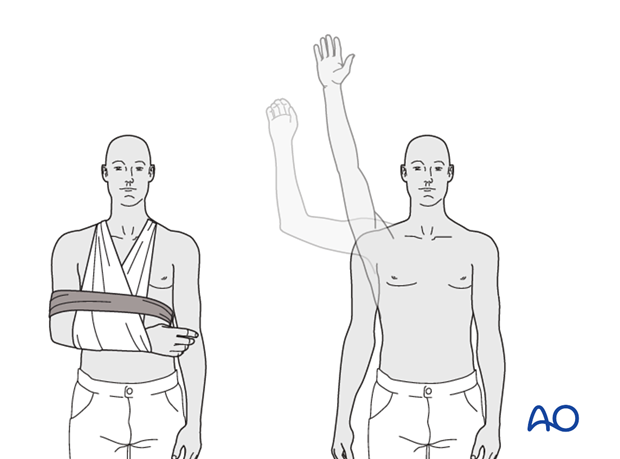

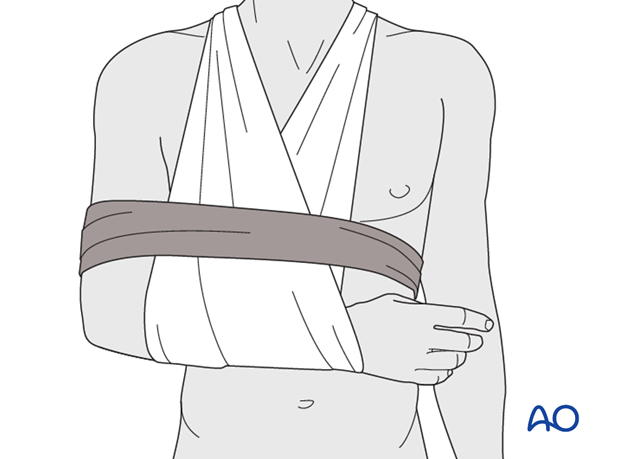

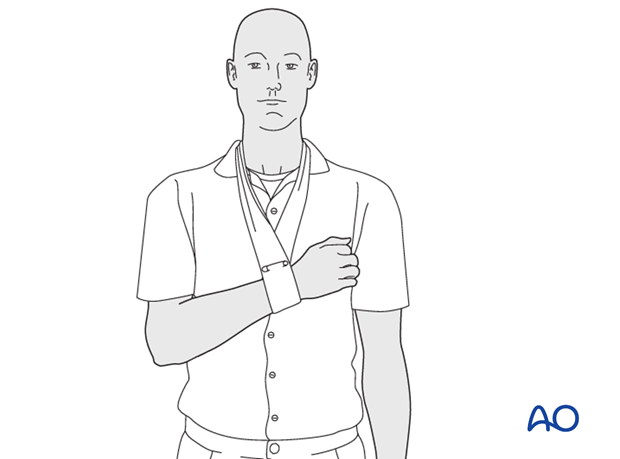

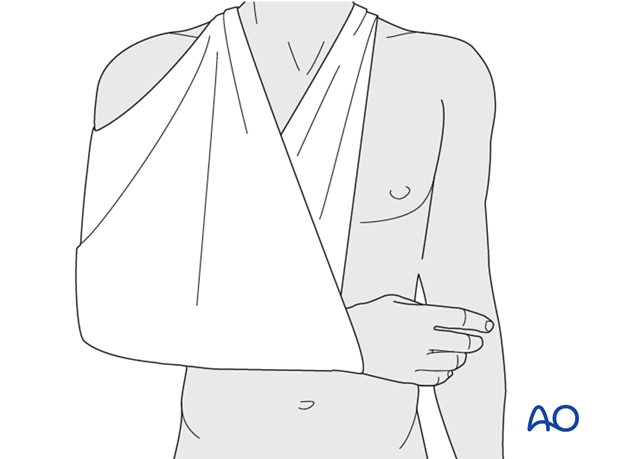

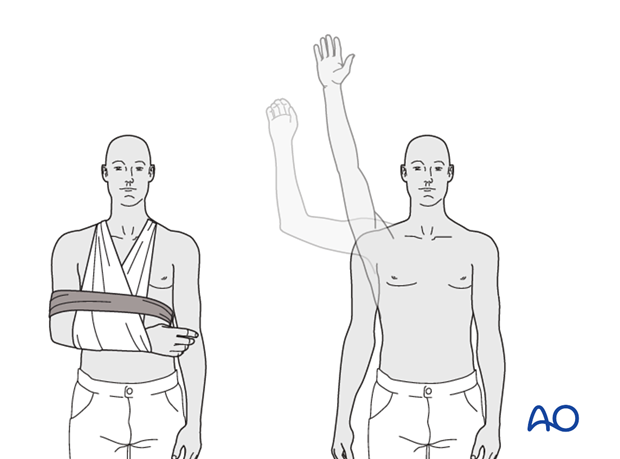

3. Sling and swath

Optimal shoulder immobilization is achieved when the upper arm and forearm are secured to the chest. Traditionally, this has been done with a sling that supports the elbow and forearm and counteracts the weight of the arm. The simplest sling is a triangular bandage tied behind the neck.

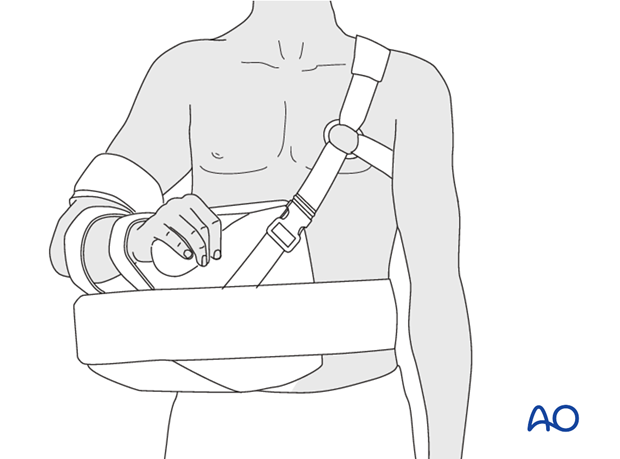

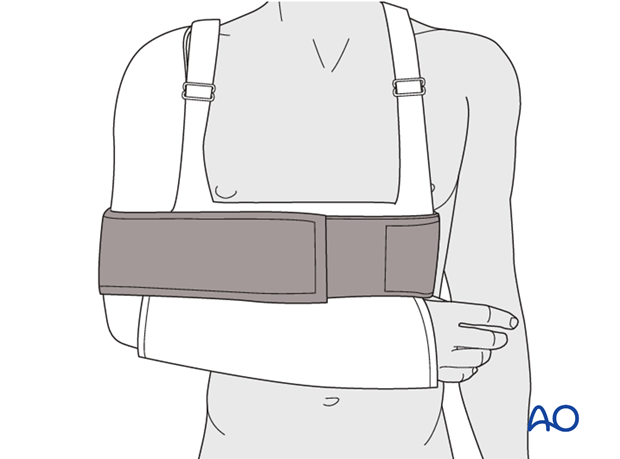

Additional support is provided by a swath which wraps around the humerus and the chest to restrict shoulder motion further, and keep the arm securely in the sling.

Commercially available devices provide similar immobilization, with or without the circumferential support of a swath.

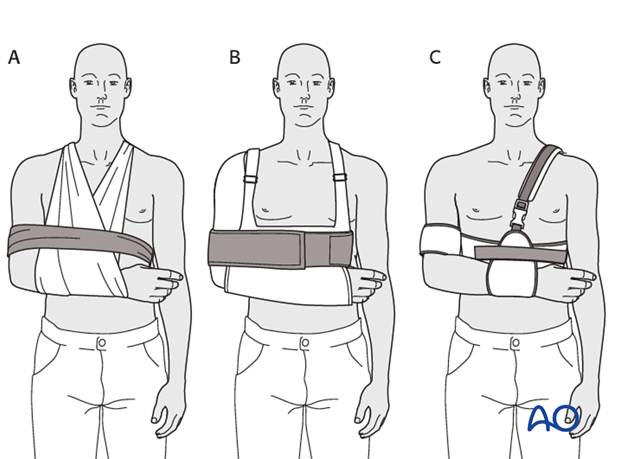

4. Shoulder immobilization

Sling and swath (A), shoulder immobilizer (B), Gilchrist bandage (C), and other such devices all provide essentially similar support for the shoulder joint.

5. Collar and cuff

The simplest arm support is a so-called collar and cuff that limits shoulder motion but does not support much of the arm’s weight. This may be desirable when gentle traction is expected to improve fracture alignment. It provides less stability than a sling, with or without swath, and must be removed for shoulder or elbow motion.

Most shoulder supports can be worn underneath or outside the patient’s clothing. The latter requires sufficient shoulder motion and comfort for dressing before the support is applied.

Keeping the hand accessible and encouraging the patient to move use wrist and fingers, helps to prevent stiffness that may be very hard to correct if it is allowed to develop.

6. Arm sling

Slight to moderate displacement of proximal humerus fractures may be treated by external support alone. A broad arm sling is the commonest method. In its simplest form, a triangular bandage is wrapped around the elbow and the forearm and tied behind the neck. The sling can be adjusted to avoid distraction at the shoulder which might cause undesirable disimpaction. Commercial slings are available to provide similar support.

7. Shoulder abduction cushion

To relieve tension on the supraspinatus tendon and greater tuberosity, one may support the arm in abduction. This can be done with a so-called airplane splint or a shoulder abduction cushion as shown.

8. Mobilization: 2-3 weeks posttrauma

Nonoperative management of proximal humerus fractures usually begins with maximal support - a sling and swath equivalent worn continuously. If the patient is uncomfortable, a sitting position may be preferred for sleeping.

A patient who is very comfortable, at the beginning of treatment or after some recovery, may need less immobilization, and even begin gentle use of the injured arm.

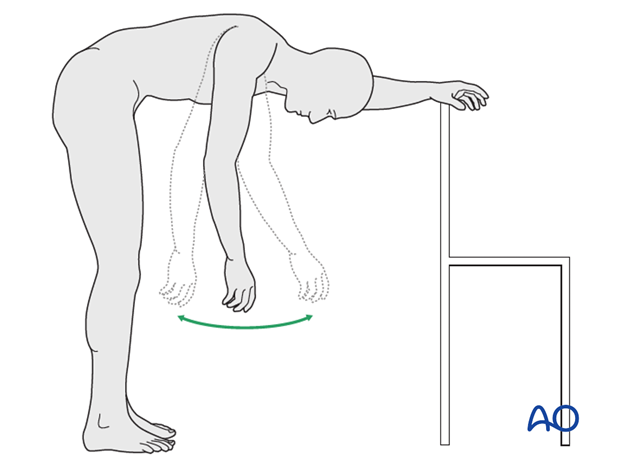

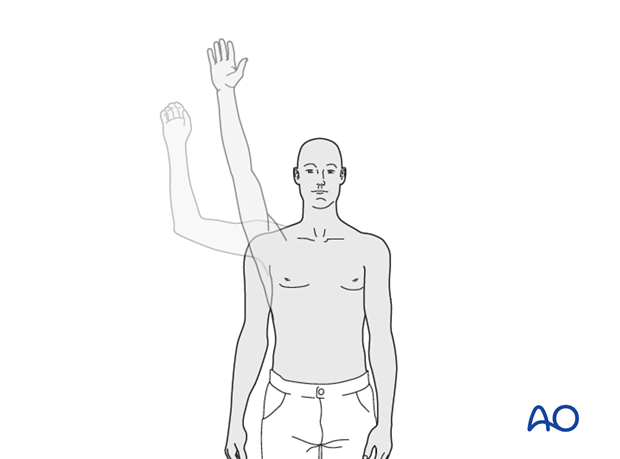

As soon as pain permits, pendulum exercises (as illustrated) should begin. Active hand and forearm use should also be encouraged.

Isometric exercises can begin as soon as tolerated for the shoulder girdle including scapular stabilizers, and the upper extremity.

X-rays should be checked to rule out secondary fracture displacement.

9. Active assisted exercises: 3-6 weeks postoperative

As comfort and mobility permit, and fracture consolidation is likely, the patient should begin active assisted motion. Physical therapy instructions and/or supervision are provided as desired and available.

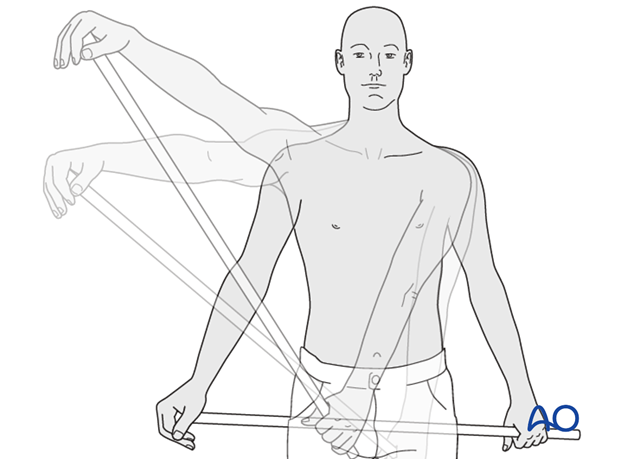

10. Shoulder therapy set: 3-6 weeks postoperative

A “shoulder therapy set” might be helpful. Typically included devices are:

1) An exercise bar, which lets the patient use the uninjured left shoulder to passively move the affected right side.

2) A rope and pulley assembly. With the pulley placed above the patient, the unaffected left arm can be used to provide full passive forward flexion of the injured right shoulder.

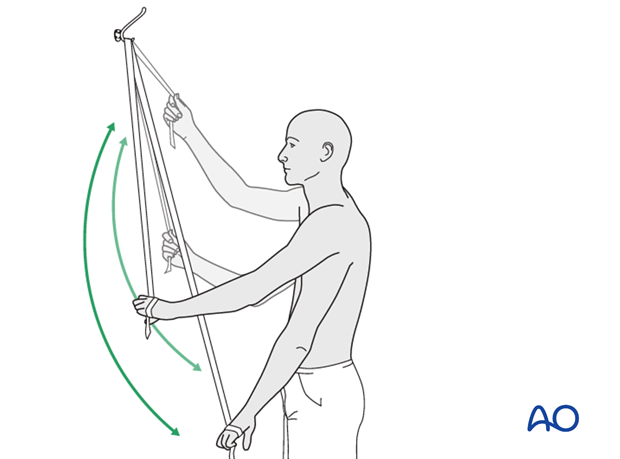

11. Strengthening: from week 6 on

As passive motion improves, and the fracture becomes fully consolidated, active motion against gravity and resistance exercises are added to build strength and endurance. Many surgeons advise forward flexion before abduction against gravity, which puts significant strain on the supraspinatus.

Elastic devices can be used to provide varying degree of resistance, and ultimately the athletic patient can progress to resistance machines and free weights.

Physical therapy instruction and supervision may be helpful for optimal rehabilitation or if the patient is not progressing satisfactorily.

Remember to monitor rotator cuff strength. Significant weakness may indicate an unidentified rotator tendon cuff rupture in need of surgical repair.

12. Pitfall: shoulder stiffness

To reduce the risk of stiffness, immobilization should be discarded as soon as possible. This can be done progressively, beginning with elimination of the swath (circumferential bandage) during the daytime and encouraging pendulum exercises.

The sling may be used on a part-time basis as soon as appropriate.

If formal physical therapy has not been prescribed, it should be considered for any patient whose range of motion is not improving as expected.

13. Overview of rehabilitation

The shoulder is perhaps the most challenging joint to rehabilitate both postoperatively and after conservative treatment. Early passive motion according to pain tolerance can usually be started after the first postoperative day - even following major reconstruction or prosthetic replacement. The program of rehabilitation has to be adjusted to the ability and expectations of the patient and the stability of the fracture. If the glenohumeral dislocation is accepted (excessively high surgical risk), rehabilitation should focus on hand and elbow use, not shoulder motion. Poor purchase of screws in osteoporotic bone, concern about soft-tissue healing (eg tendons or ligaments) or other special conditions (eg percutaneous cannulated screw fixation without tension-absorbing sutures) may enforce delay in beginning passive motion, often performed by a physiotherapist.

The full exercise program progresses to protected active and then self-assisted exercises. The stretching and strengthening phases follow. The ultimate goal is to regain strength and full function.

Postoperative physiotherapy must be carefully supervised. Some surgeons choose to manage their patient’s rehabilitation without a separate therapist, but still recognize the importance of carefully instructing and monitoring their patient’s recovery.

Activities of daily living can generally be resumed while avoiding certain stresses on the shoulder. Mild pain and some restriction of movement should not interfere with this. The more severe the initial displacement of a fracture, and the older the patient, the greater will be the likelihood of some residual loss of motion.

Progress of physiotherapy and callus formation should be monitored regularly. If weakness is greater than expected or fails to improve, the possibility of a nerve injury or a rotator cuff tear must be considered.

With regard to loss of motion, closed manipulation of the joint under anesthesia, may be indicated, once healing is sufficiently advanced. However, the danger of fixation loosening, or of a new fracture, especially in elderly patients, should be kept in mind. Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions or even open release and manipulation may be considered under certain circumstances, especially in younger individuals.

Progressive exercises

Mechanical support should be provided until the patient is sufficiently comfortable to begin shoulder use, and/or the fracture is sufficiently consolidated that displacement is unlikely.

Once these goals have been achieved, rehabilitative exercises can begin to restore range of motion, strength, and function.

The three phases of nonoperative treatment are thus:

- Immobilization

- Passive/assisted range of motion

- Progressive resistance exercises

Immobilization should be maintained as short as possible and as long as necessary. Usually, immobilization is recommended for 2-3 weeks, followed by gentle range of motion exercises. Resistance exercises can generally be started at 6 weeks. Isometric exercises may begin earlier, depending upon the injury and its repair. If greater or lesser tuberosity fractures have been repaired, it is important not to stress the rotator cuff muscles until the tendon insertions are securely healed.

Special considerations

Glenohumeral dislocation: Use of a sling or sling-and-swath device, at least intermittently, is more comfortable for patients who have had an associated glenohumeral dislocation. Particularly during sleep, this may help avoid a redislocation.

Weight bearing: Neither weight bearing nor heavy lifting are recommended for the injured limb until healing is secure.

Implant removal: Implant removal is generally not necessary unless loosening or impingement occurs. Implant removal can be combined with a shoulder arthrolysis, if necessary.

Shoulder rehabilitation protocol

Generally, shoulder rehabilitation protocols can be divided into three phases. Gentle range of motion can often begin early without stressing fixation or soft-tissue repair. Gentle assisted motion can frequently begin within a few weeks, the exact time and restriction depends on the injury and the patient. Resistance exercises to build strength and endurance should be delayed until bone and soft-tissue healing is secure. The schedule may need to be adjusted for each patient.

Phase 1 (approximately first 3 weeks)

- Immobilization and/or support for 2-3 weeks

- Pendulum exercises

- Gently assisted motion

- Avoid external rotation for first 6 weeks

Phase 2 (approximately weeks 3-9)

If there is clinical evidence of healing and fragments move as a unit, and no displacement is visible on the x-ray, then:

- Active-assisted forward flexion and abduction

- Gentle functional use week 3-6 (no abduction against resistance)

- Gradually reduce assistance during motion from week 6 on

Phase 3 (approximately after week 9)

- Add isotonic, concentric, and eccentric strengthening exercises

- If there is bone healing but joint stiffness, then add passive stretching by physiotherapist