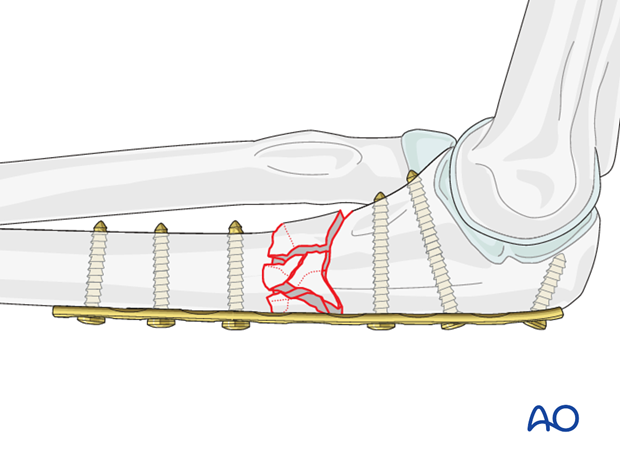

Bridge plate

1. Principles

Bridge plating uses the plate as an extramedullary splint. It must be fixed securely to the two main fragments. The intermediate fracture zone is left untouched. Anatomical reduction of the intermediate fragments is not necessary but alignment, rotation and length of the bone must be restored.

Direct manipulation of the intermediate fracture fragments risks disturbing their blood supply. If the soft-tissue attachments are preserved, and the fragments are relatively well aligned and stable, healing is predictable.

Alignment of the main fragments can usually be achieved indirectly utilizing traction and soft tissue tension.

Mechanical stability, provided by the bridging plate, is adequate for secondary healing (callus formation).

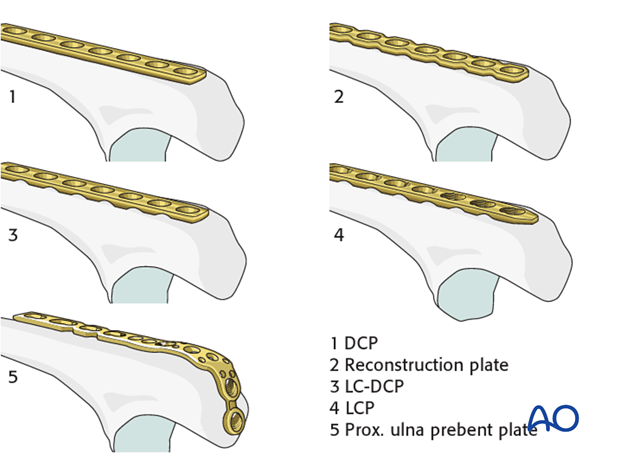

2. Choice of implant

3.5 mm DCP, reconstruction plate, LC-DCP, LCP or a specific proximal ulna prebent plate can be used.

As bridge plating spans a long section of the bone, the length of the implant has to be chosen accordingly. The longer the fracture zone, the longer the plate to be used.

Note: A locked plate with locking head screws is the preferred choice in osteoporotic bone.

Double plating with one plate posteriorly (tension side of the bone) and an additional smaller plate (2.7) medially or lateral can increase the stability.

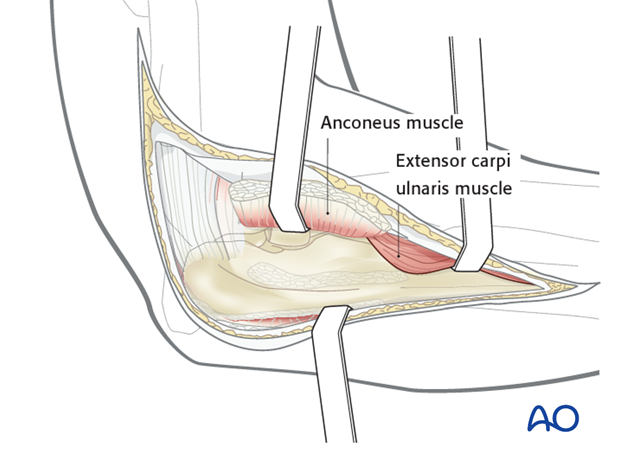

3. Plate insertion options

Bridge plates in the proximal ulna can be inserted through an open exposure with minimal soft-tissue damage. In open bridge plating, it is important to preserve soft-tissue attachments to the fracture fragments.

A bridge plate may be applied to medial, lateral, or posterior surfaces of the proximal ulna. The choice depends on other injuries, soft-tissue condition and surgeon’s preference. Positioning the plate posteriorly facilitates the sagittal reduction although is slightly more prominent.

Bridge plating can be done with a minimally invasive approach, which requires fluoroscopic monitoring. In minimally invasive surgery, a bridge plate is applied through one proximal and one distal incision, just wide enough for the plate. Control of reduction may be more difficult than with an atraumatic open technique.

Note: In healthy bone, it is not necessary to fill all screw holes proximal and distal to the fracture zone. However, in osteoporotic bone it is safer to use all plate holes outside the fracture zone, or to use an LCP. Multiple screws add torsional stability and decrease the risk of failure.

4. Positioning and approach

Positioning

This procedure is normally performed with the patient either in a lateral position or in a supine position for posterior access.

Approach

For this procedure a posterolateral approach is normally used.

5. Preliminary reduction

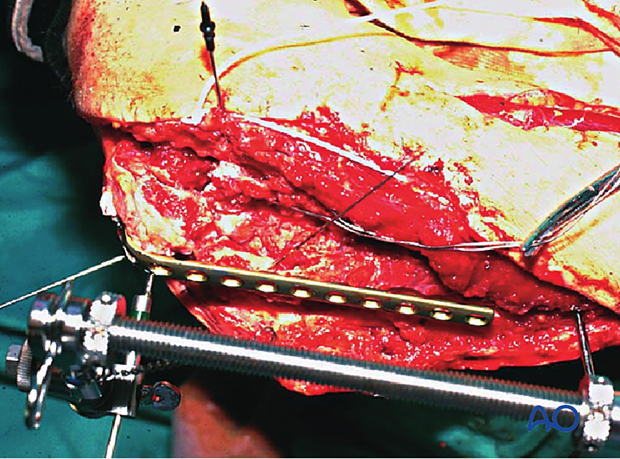

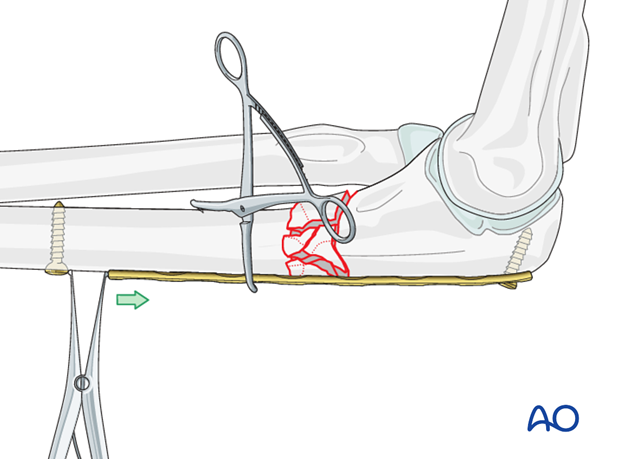

Reducing a multifragmentary proximal ulnar fracture may be difficult. Reduction can be achieved with a small distractor as shown, or an external fixator with minimal exposure and manipulation of the fracture zone. This is difficult to do with manual traction alone.

Overall alignment of the proximal ulna may be restored with an appropriately contoured plate, fixed proximally with one screw and positioned over the distal fragment.

6. Plate application

Plate application in the proximal fragment

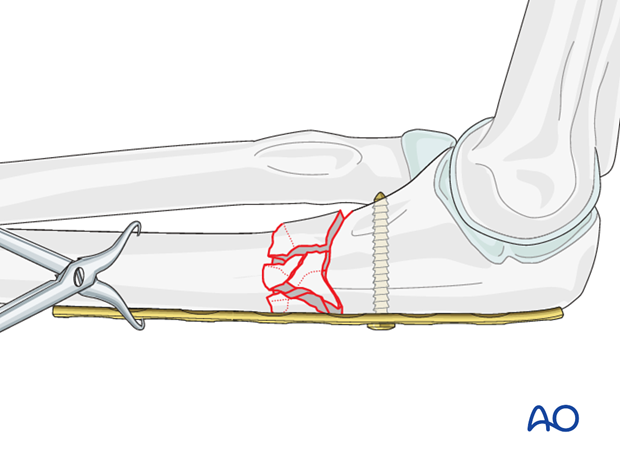

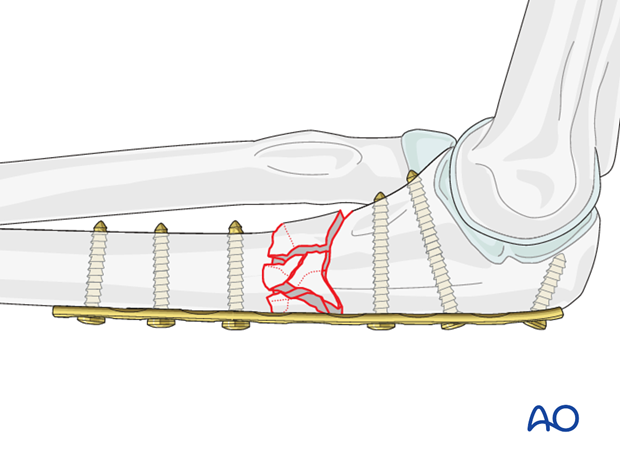

Apply the properly contoured plate to the proximal fragment, so that it is correctly aligned with the ulnar axis (both sagittal and coronal planes). When the plate fits satisfactorily against the proximal segment, it can be attached provisionally with a single screw.

While the plate is held manually against the bone, the screw is inserted. Sometimes it is helpful to clamp the plate to the proximal fragment of the ulna with a bone forceps.

In the lateral view the plate must be parallel to the longitudinal axis of the ulna. If alignment is satisfactory, apply a second screw to secure the plate proximally in this correct position.

Alignment and fixation of the distal fragment

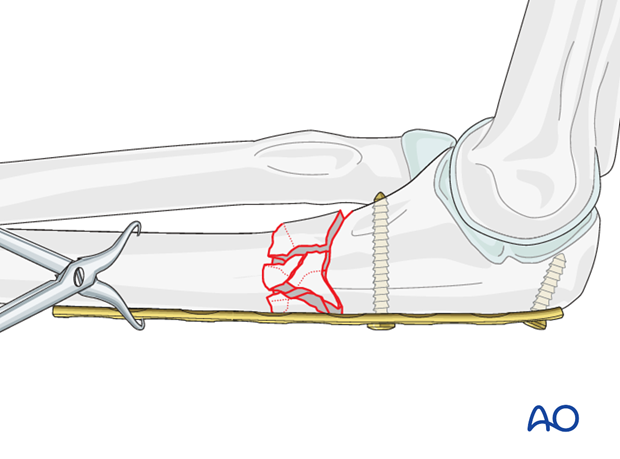

Once the plate is satisfactorily fixed proximally, bring the distal fragment into alignment against the plate.

Often the plate can be held manually against the bone and a first distal screw is inserted after rotation and length are restored.

Sometimes it is helpful to clamp the plate to the bone with a bone forceps as shown. Carefully pass the forceps close against the bone during application in order to avoid injury to adjacent nerves.

Alternatively, after the plate is fixed proximally with one or two screws, insert a screw distal to the plate. The fracture zone can be lengthened and disimpacted by using a laminar spreader between the distal screw and the plate. Secure reduction with a distal screw.

7. Finish fixation

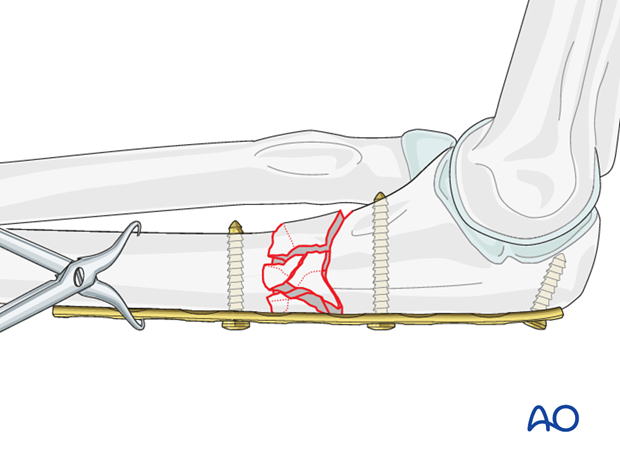

If alignment is satisfactory, add a second distal screw and reconfirm alignment.

Use at least three bicortical screws in each main fragment. In both major fragments, place the first screw as close as practicable to the fracture, and the second at the end of the plate.

Confirm reduction, plate position, and screw length under image intensification.

Note: Beware of penetrating the joint with a screw in the proximal fragment.

8. Postoperative treatment following ORIF

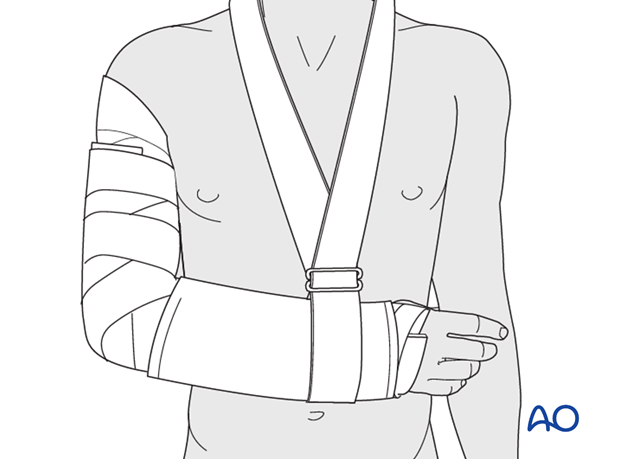

Postoperatively, the elbow may be placed for a few days in a posterior splint for pain relief and to allow early soft tissue healing, but this is not essential. To help avoid a flexion contracture, some surgeons prefer to splint the elbow in extension.

If drains are used, they are removed after 12–24 hours.

Mobilization

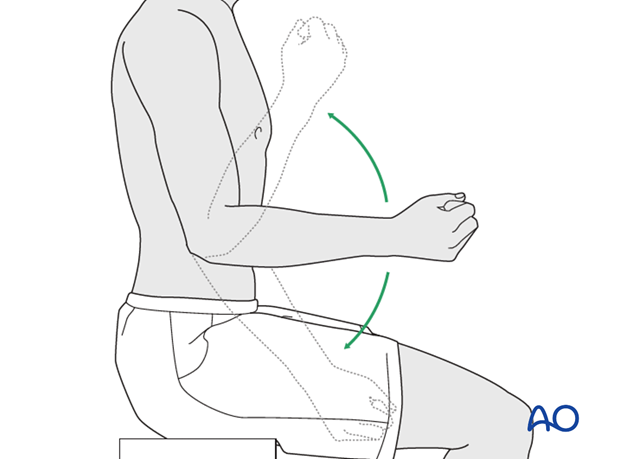

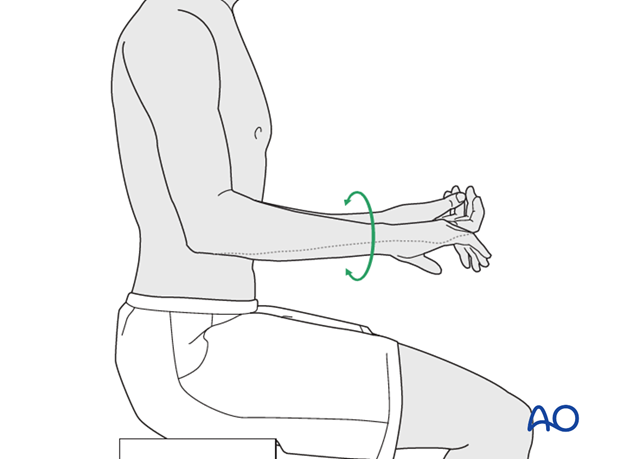

Active assisted motion is encouraged within the first few days including gravity-assisted elbow flexion and extension. Encourage the patient to move the elbow actively in flexion, extension, pronation and supination as soon as possible. Delay exercises against resistance until healing is secure.

Use of the elbow for low intensity activities is encouraged, but should not be painful.

Range of motion must be monitored to prevent soft tissue contracture.

Prevent loading of the elbow for 6–8 weeks.

Monitor the patient to assess and encourage range of motion, and return of strength, endurance, and function, once healing is secure.

Follow up

The patient is seen at regular intervals (every 10–20 days at first) until the fracture has healed and rehabilitation is complete.

Implant removal

As the proximal ulna is subcutaneous, bulky plates and other hardware may cause discomfort and irritation. If so, they may be removed once the bone is well healed, 12–18 months after surgery, but this is not essential.