Repair of lateral collateral ligaments

1. Principles

The collateral ligaments of the elbow will heal at proper tension if the elbow remains concentrically reduced for 3 to 4 weeks. This is true even when the elbow has been dislocated for several months - get the elbow in place and the ligaments scar and heal into place.

Some surgeons have reported the use of tendon grafts to treat acute, subacute, and chronically dislocated elbows.

In the acute stage this is presumably to add additional stability.

It is much easier to use strategies for maintaining elbow reduction (repair or replacement of all fractures, suture reattachment of avulsed collateral ligaments, and selective temporary mechanical maintenance of reduction (eg cross pins, external fixation, internal fixation).

2. Preparation

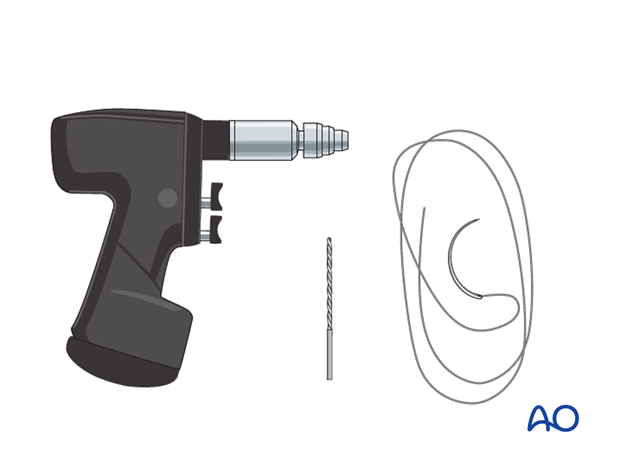

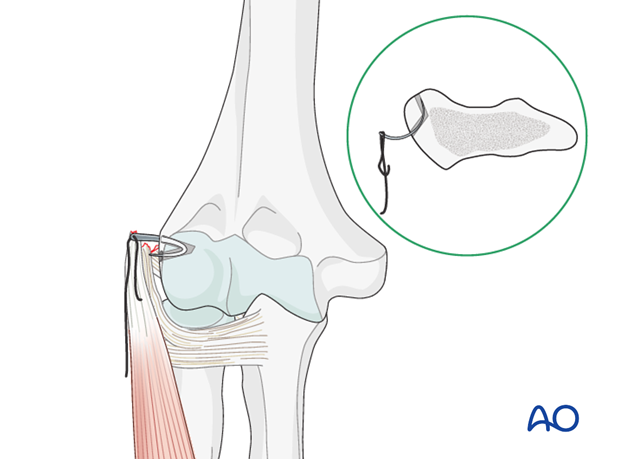

Instruments and implants for suture fixation through drill holes

To reattach an avulsed ligament with or without a small bony avulsion, sutures can either be passed through drill holes or a suture anchor can be used.

The drill holes should be 1.5 to 2 millimeters and can exit posteriorly.

0 or 2-0 braided nonabsorbable suture is generally recommended.

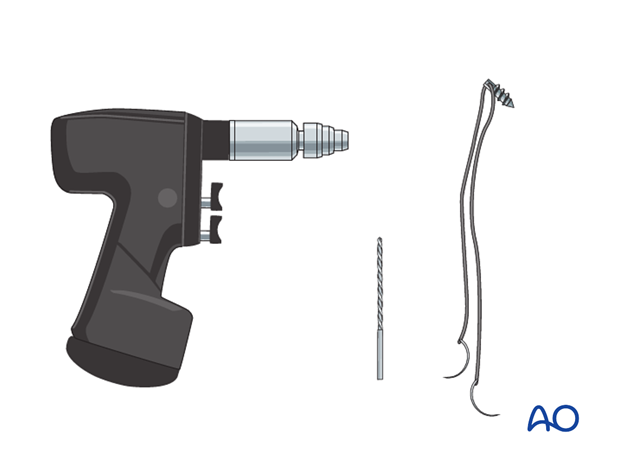

Instruments and implants for anchor fixation

One anchor should be sufficient. It is generally placed at the isometric (center) point of the lateral epicondyle. Use a large anchor with the appropriate drill.

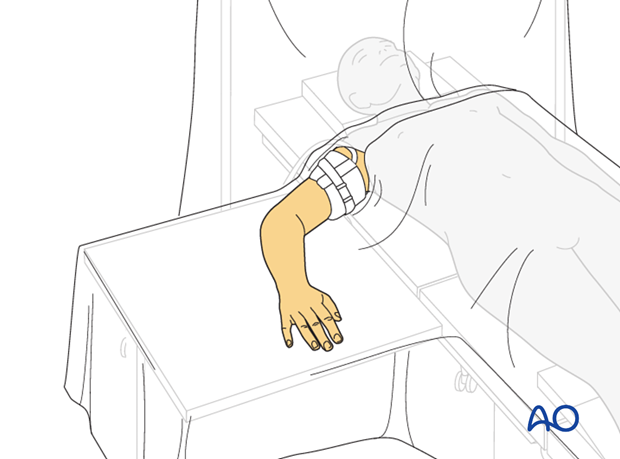

Anesthesia and positioning

General anesthesia is recommended. A sterile tourniquet allows better access to the elbow and makes it easier to manipulate the arm.

The patient is placed supine with the arm supported on a hand table and draped up to the shoulder.

3. Exposure

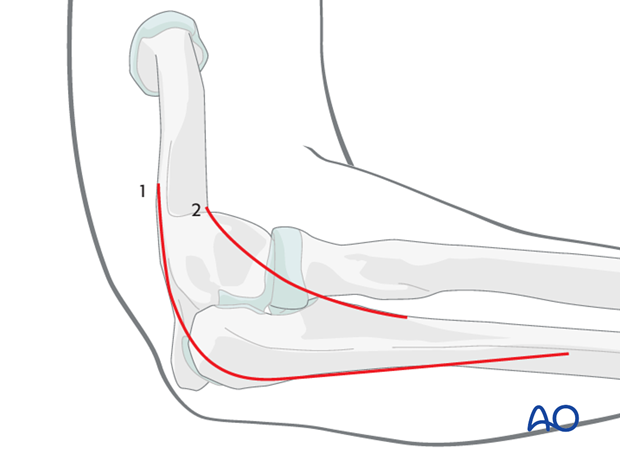

The skin incision can either be posterior with a lateral skin flap or direct lateral.

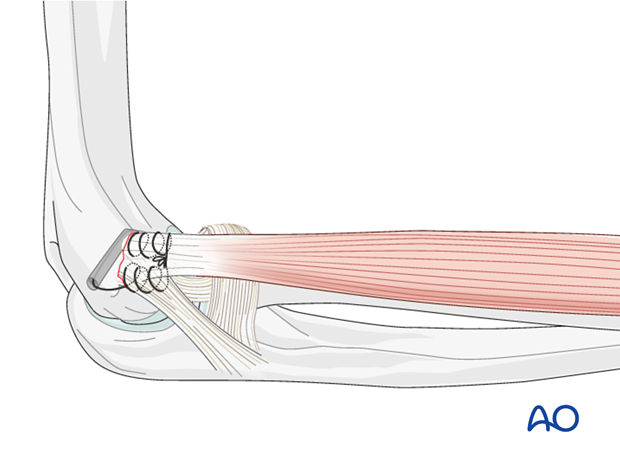

The lateral collateral ligament typically avulses from the lateral epicondyle along with the common wrist and digit extensor musculature when it fails. There is no need to separate the ligament.

Use and extend the injury from trauma to gain access for fracture repairs.

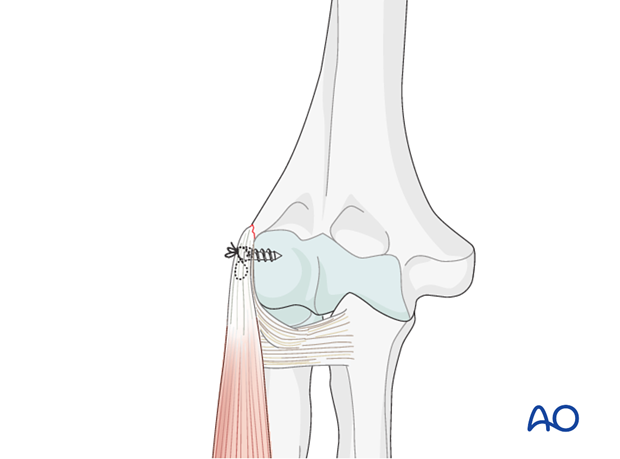

4. Repair

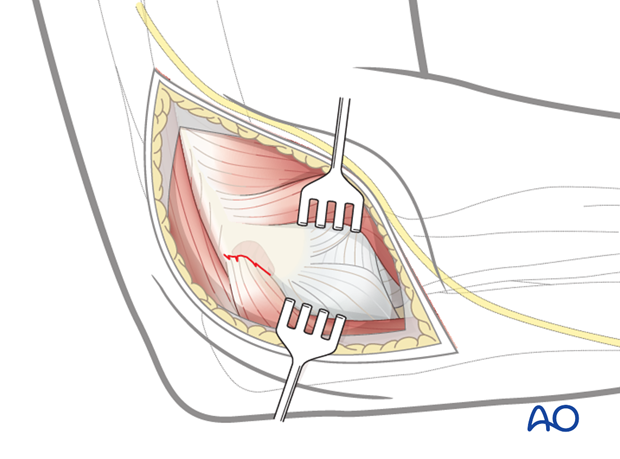

The ligament is kept in association with the extensor muscle mass.

The confluence of muscle and ligament is reattached to the lateral epicondyle with either suture anchors or suture passed through drill holes.

A key fixation point is just anterior and inferior to the central access point where the ligament typically originates.

Suture repair

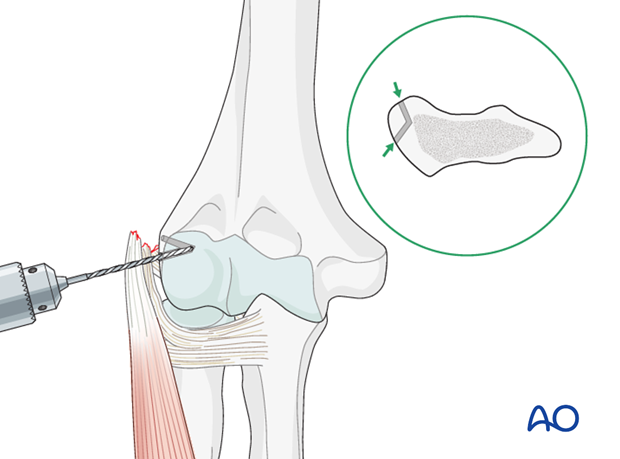

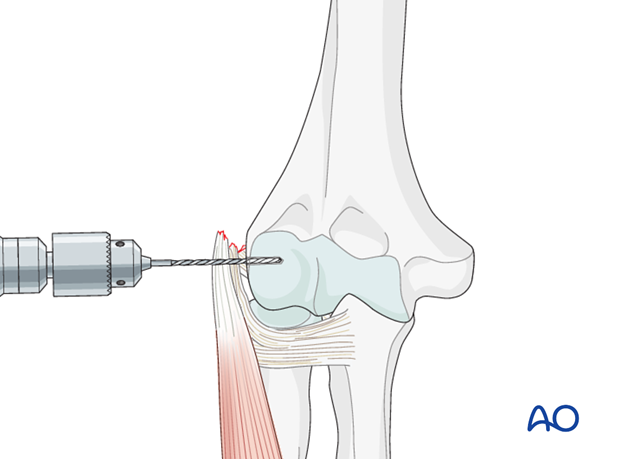

A drill hole is made at the epicondyle and exits posteriorly.

The suture is passed from posterior to anterior through the hole on the suture needle. The suture needle can be straighted somewhat if needed.

There is no single correct way to pass the sutures through the sleeve of ligament and muscle. One way is to pass the suture(s) through the posterior part of the muscle/ligament sleeve and then through the anterior part, overlapping them somewhat.

After that knot is tightened, the suture can be used to close the distal and proximal intervals using a running or running-locking suture.

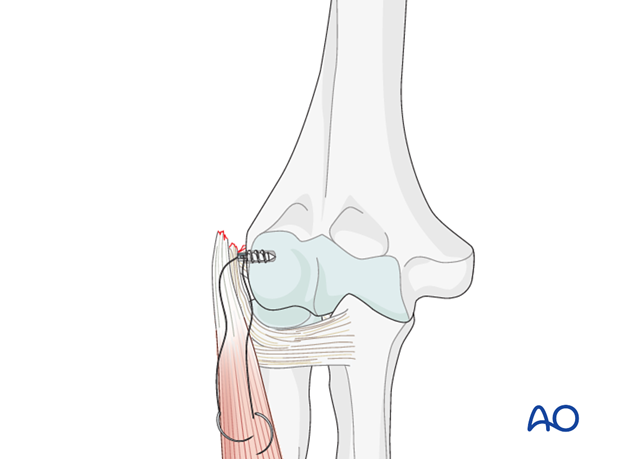

Anchor fixation

A drill hole is made near the isometric center of the epicondyle for the anchor (this step is not necessary if self-drilling, self-tapping anchors are used).

The anchor is inserted.

The suturing then proceeds as described above.

There is no single correct way to pass the sutures through the sleeve of ligament and muscle. Here a figure of eight pattern has been used.

After that knot is tightened, the suture can be used to close the distal and proximal intervals using a running or running-locking suture.