MIO - Iliosacral screw for sacrum

1. Introduction

Iliosacral screw (ISS) fixation is a fluoroscopically guided, percutaneous procedure. Its primary use is for fixation of satisfactorily reduced sacral fractures or sacro-iliac joint disruptions (described in a separate procedure). Anatomic reduction must be obtained before ISS insertion.

Screw placement and angulation will depend on the injury and the patients specific anatomy (variations are common) .

Principles of ISS fixation for sacral fracture

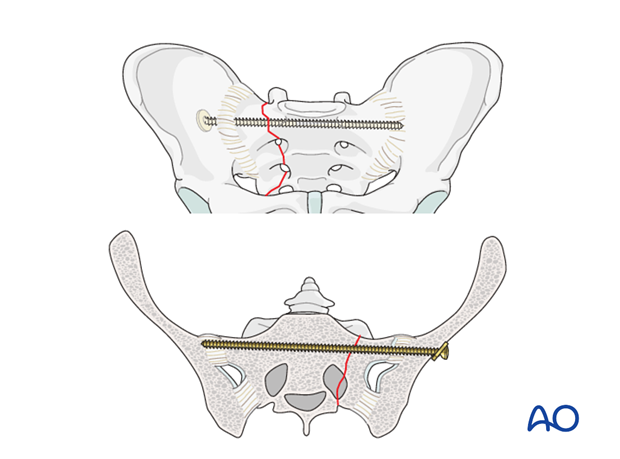

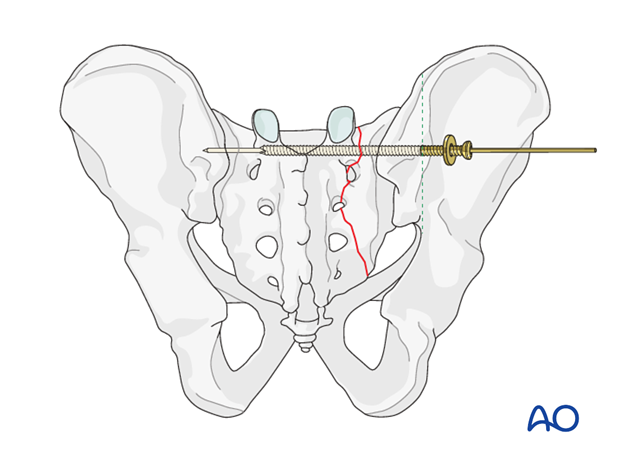

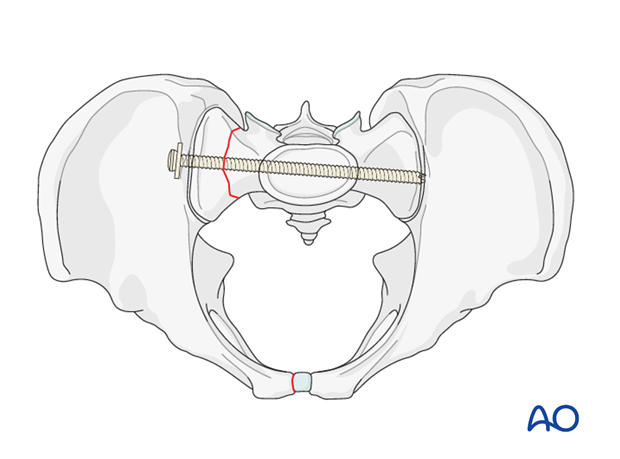

ISSs for sacral alar fractures are usually oriented transversely because this is the path of a transsacral channel. Screw channels for sacral fractures are narrow and precise screw placement is therefore essential.

ISS for sacral fractures can be unilateral, extending far into the contralateral sacral ala, transsacral, or transiliac extending beyond the contralateral ilium where a suitable nut on the screw threads can enhance fixation.

Compression of a comminuted alar fracture may injure a nerve root within the fracture zone. Thus, a fully threaded (position) screw may be preferable to a lag screw for ISS fixation. However, a screw that maintains excessive distraction increases the risk of nonunion. A washer is advisable for secure fixation on the ipsilateral side.

Fixation failure may occur, especially with grossly unstable injuries. Fixation can be enhanced by one or more of the following:

- 1 or 2 additional screws (S1 or S2 level)

- Supplementary posterior plates

- Spinopelvic fixation (especially for comminuted transforaminal vertical sacral fractures).

- Anterior arch fixation increases stability

Teaching video

AO teaching video: Pelvis – Sacral fracture – Reduction and fixation with iliosacral screws

2. Preoperative planning

Pre-operative planning for repair of complex pelvic ring injuries

An explicit, written pre-operative plan is strongly encouraged. In addition to overall assessment and preoperative planning, specific considerations are required for ISS.

These are:

- Patient's individual pelvic anatomy (normal vs. dysmorphic)

- Patient's specific sacral fracture configuration

- Optimal ISS type, location. and length

- Selection of screw channels

- Need for enhanced fixation (see above)

3. Imaging

CT analysis

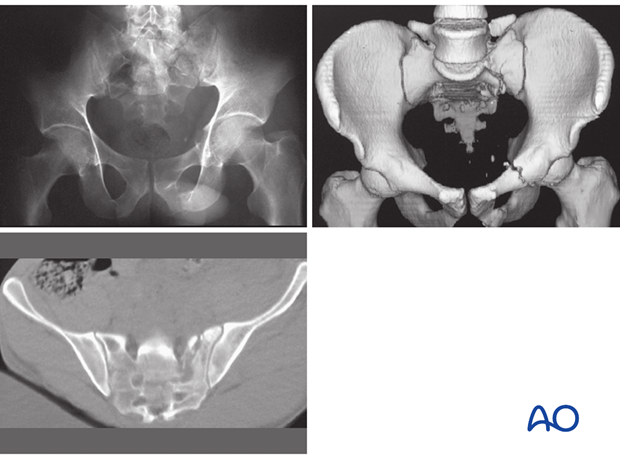

High quality pelvic CTs are crucial for planning reduction maneuvers and safe, effective paths for ISS placement.

In addition to trans-axial images, sagittal and coronal reconstructions should be studied, with x-ray or CT views of the entire pelvis, including 3-D images if available.

Comprehensive imaging demonstrates each site of injury, including its displacement and signs of instability, as well as base-line anatomic features, including bone quality and morphology.

Essential C-arm Views for ISS

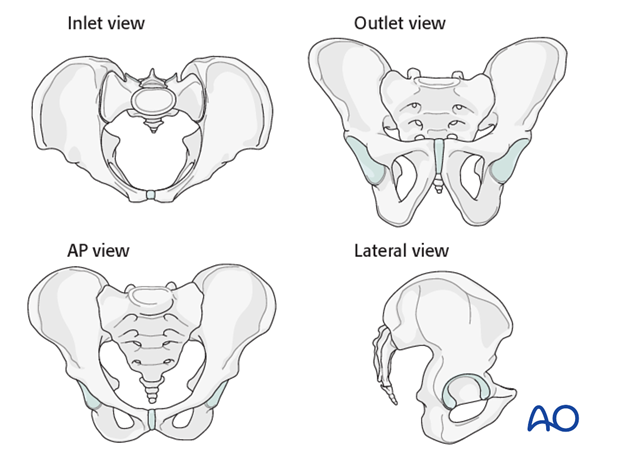

In addition to proper AP, inlet, and outlet views, a true lateral radiograph centered on S1 is essential for IS screw insertion.

The true lateral x-ray shows the midline profile of the sacral promontory, and the iliac cortical densities, which mark the anterosuperior surface of the ala.

Confirm that the lateral view is indeed true, without rotation. The sciatic notch outlines should be superimposed.

C-arm set-up, and resulting images should finalized after the patient is anesthetized and positioned, before sterile drapes are applied.

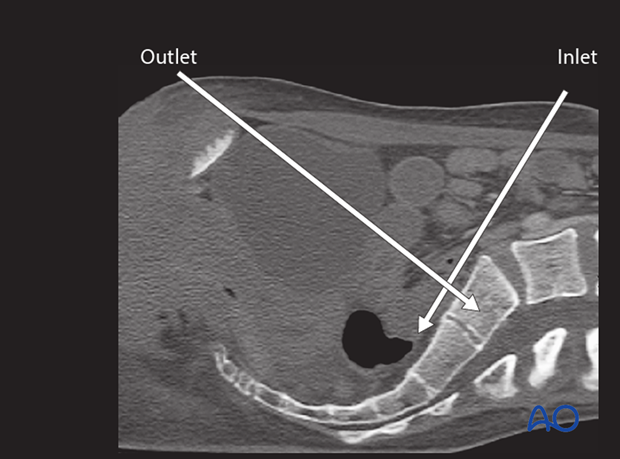

Patient-specific inlet & outlet views.

Individual variation of pelvic inclination is significant enough that customized inlet and outlet angles should be chosen for use during ISS. These are based upon a midline sagittal CT reconstruction showing the sacrum. The inlet angle should be tangent to the anterior cortex of S1. The outlet angle is perpendicular to the “midline” of the trapezoidal S1 body. The C-arm must be centered over the site of interest.

An optimal outlet view shows the upper border of the pubis overlying the second sacral vertebra.

Intraoperative C-arm imaging

During setup for surgery, it is important to confirm the adequacy of C-arm imaging. This is essential to avoid errors in ISS placement.

The following should be clearly identifiable:

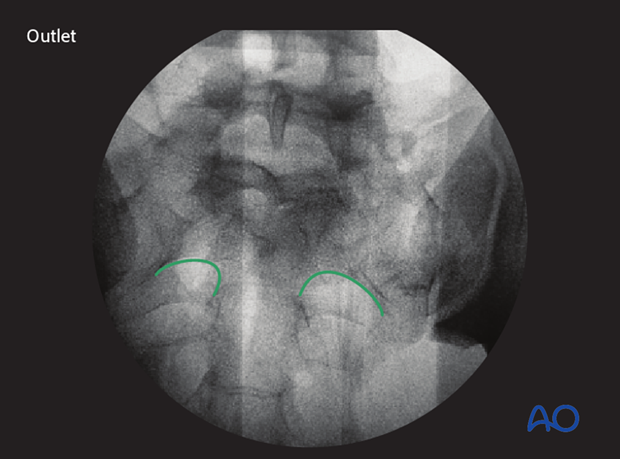

- sacral foramina in outlet view (outlet view)

- spinal canal (inlet view)

- S1 body (inlet view)

If these structures cannot be clearly seen, a safe trajectory for the iliosacral screw cannot be determined. Fluoroscopically guided fixation must be postponed replaced with an open procedure. (Obese patients, extensive bowel gas, and/or overlying radiographic contrast material are typical problems.).

Location of S1 nerve root tunnels

Good quality fluoroscopic views indicate the course of upper sacral nerve root tunnels.

In the outlet view, the appearance is similar to a hip spica cast, with its upper part formed by the midline sacral spinal canal, and the root tunnels being the legs of the spica.

In the inlet view, the root tunnels travel from central to anterolateral, exiting through anterior cortical lucencies.

On the lateral view the S1 root tunnel is caudal/posterior to the iliac cortical density, beneath the superior cortex of the sacral ala.

4. Sacral anatomy variations

Variable in utero segmentation of the lumbo-sacral somites produces abnormal (“dysmorphic”) upper sacral anatomy in approximately one-third of patients. These variations must be recognized because they compromise normally safe intraosseous pathways for ISS.

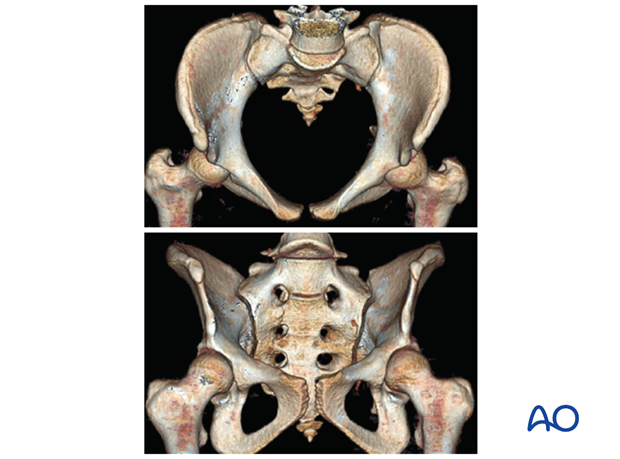

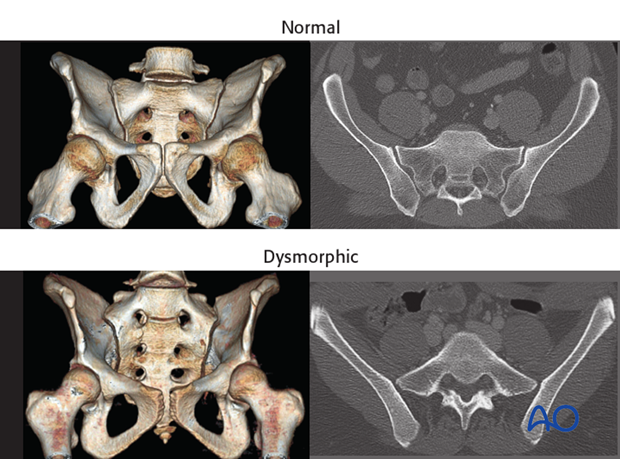

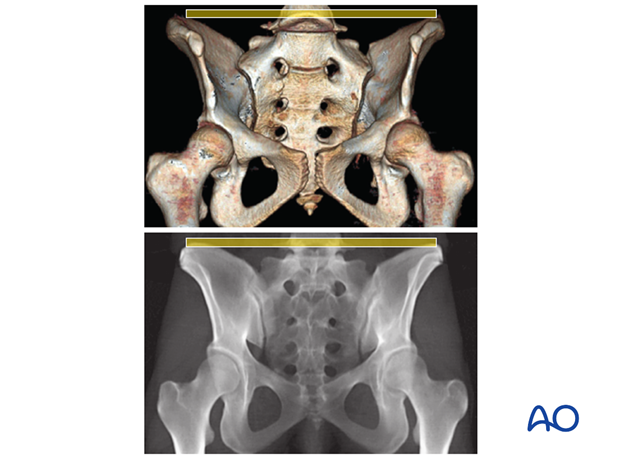

Normal vs. dysmorphic sacral anatomy

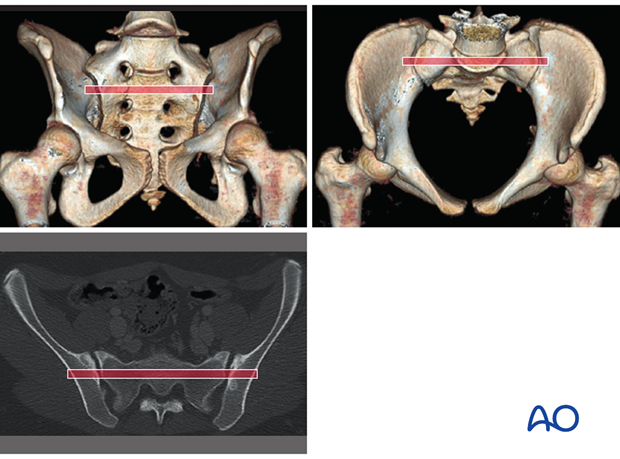

The upper images show a normal pelvis; the lower ones are of a dysmorphic pelvis.

Notice, on the 3D CTs, the differences in sacral alar anatomy, with corresponding upper sacral segment deficiencies on the dysmorphic axial CT view.

In such cases, the second sacral level may be better for an iliosacral screw

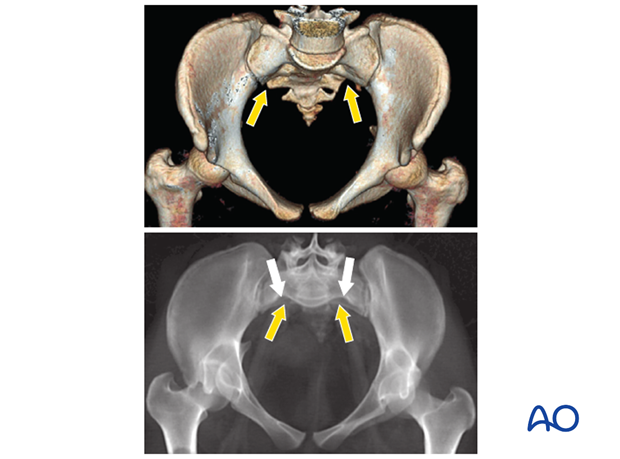

Features of dysmorphic pelvis

Sacral deformities may be unilateral or bilateral. Bilateral dysmorphism may be symmetrical, or not.

This case shows an individual with symmetrical upper sacral dysmorphism.

The lumbosacral disc is near the level of the iliac crests, not below them as is normal. There is a residual disc between the upper and second sacral segments. The uppermost anterior sacral foramina are not round, as the lower ones are. The superior alar slope is steeper, from medial to lateral, and from posterior to anterior.

The upper sacral alar anterior cortical limit appears as an indentation (white arrows) relative to the alar anterior cortical of the second sacral segment (yellow arrows). The upper and second sacral alar anterior cortical limits are different but easily seen on the inlet view. The surgeon must understand these differences and then visualize them under image intensifier in the operating room because iliosacral screws must remain posterior to these alar cortical limits.

5. Safe screw channels for sacral fracture fixation

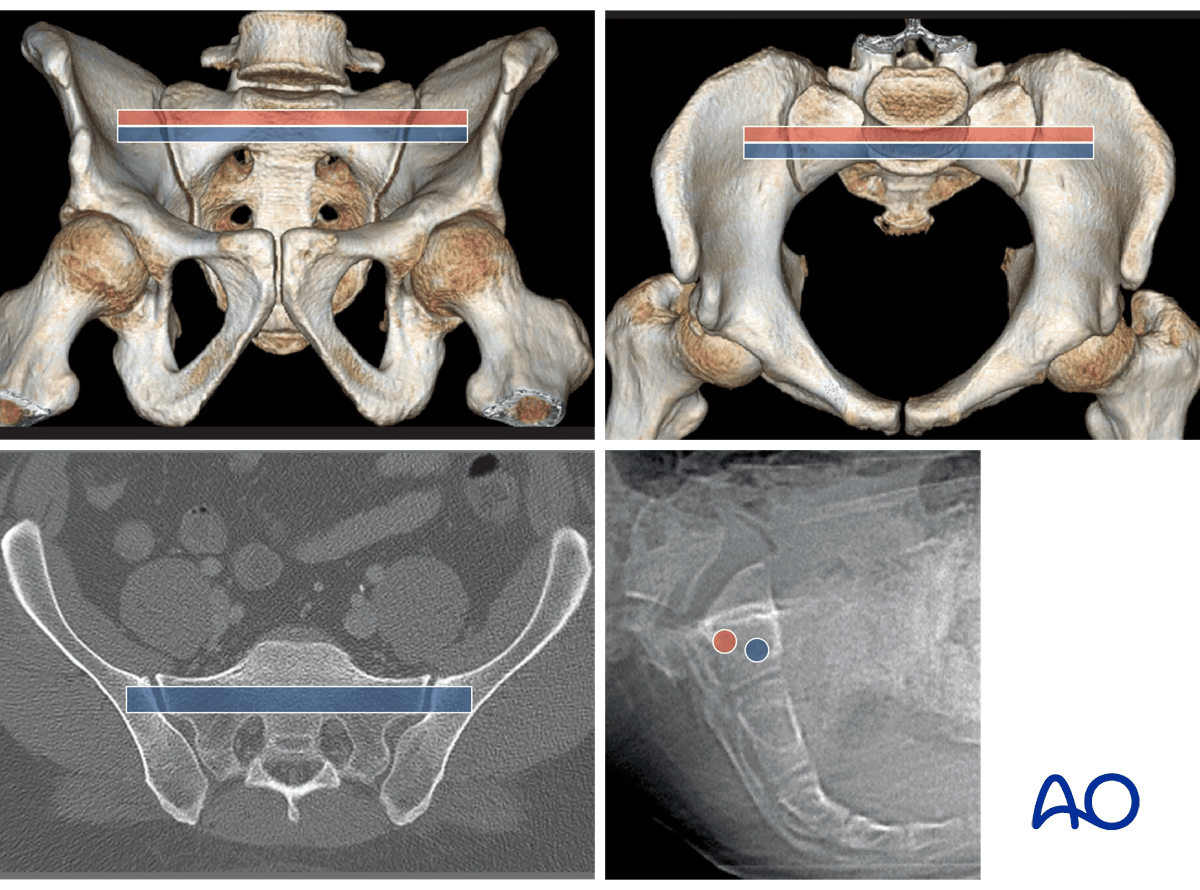

Patients with normal anatomy

For fixation of sacral fractures in a nondysmorphic pelvis, an ISS can be placed in the blue channel.

A second screw can be added, through the smaller (posterior) red channel, to increase fixation stability.

A third screw, if required, may be placed transversely through a channel in the upper anterior second sacral body.

These images illustrate the channel for an S2 transsacral screw in a normal pelvis.

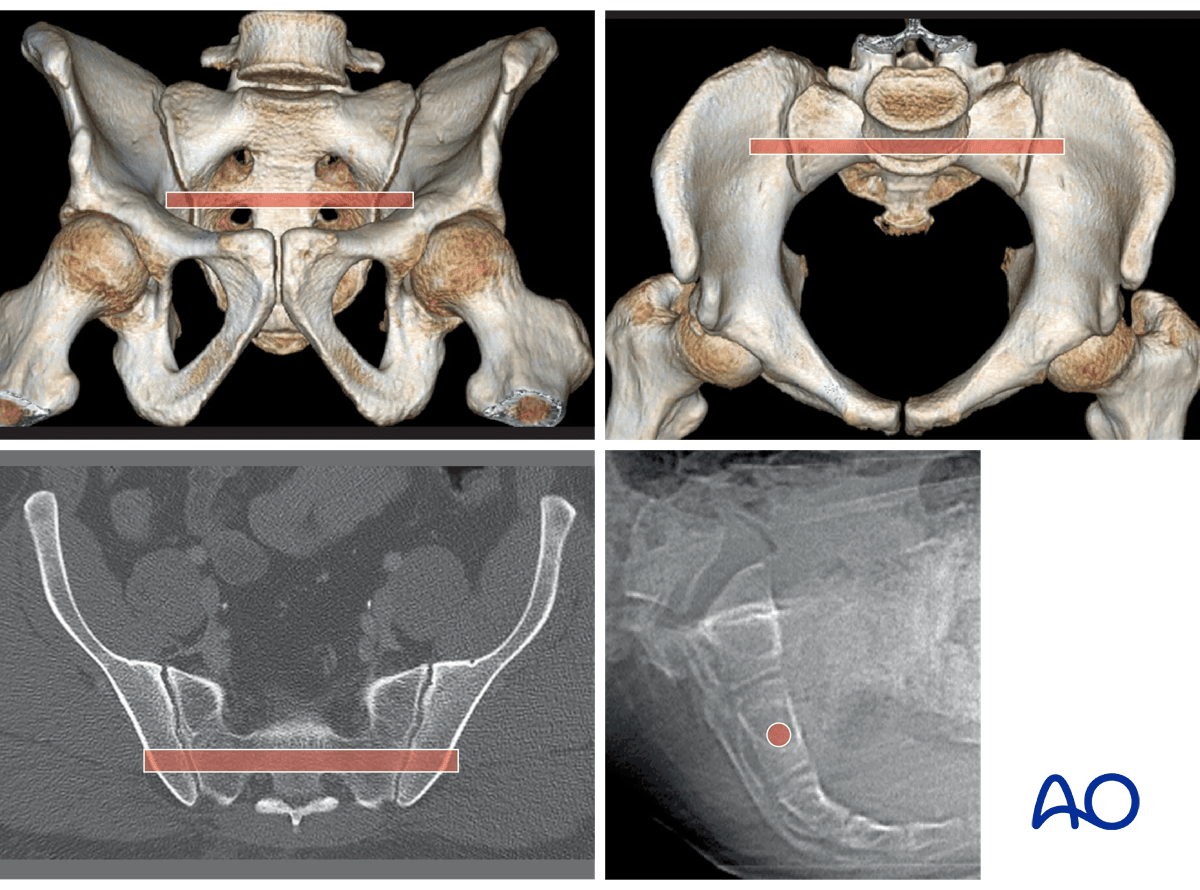

Dysmorphic sacrum

In this dysmorphic pelvis, the red channel is placed through an adequate S2 segment, rather than the dysmorphic first segment.

Upper left - Outlet: the pathway is slightly cranial to the second sacral neural foramina.

Upper right – Inlet: the 2nd sacral segment lacks the anterior indentations of the 1st .The anterior cortical surface of the 2nd is visible below the indentations of the 1st

(If upper sacral segment (oblique) screws are also desired, they should be inserted before the second segment transsacral screw, since the latter screw prevents visualization of the upper segment anterior alar indentations, which are the anterior limit to upper segment screw placement)

6. Reduction

ISS fixation requires an essentially anatomically reduced sacral fracture. Displacement of greater than 5mm renders this procedure unsafe. Displacement may make screw insertion impossible without causing intraosseous nerve root injury or resulting in an extraosseous screw that threatens adjacent neurovascular structures.

If displacement remains greater than 5 mm after closed reduction, open reduction with posterior plate fixation should be considered.

Some rotationally displaced sacral fractures (B1.2 type fractures) can be reduced closed by correcting external rotation of the hemipelvis. If this is successful, ISS may proceed.

A totally unstable sacral fracture is difficult to reduce anatomically without open technique. Thus, ISS is rarely used for such injuries, but it is possible to add ISS fixation after an open anatomical reduction.

7. ISS Fixation Procedure

Before beginning an ISS screw fixation procedure, appropriate preoperative planning for screw type and location needs to be completed.

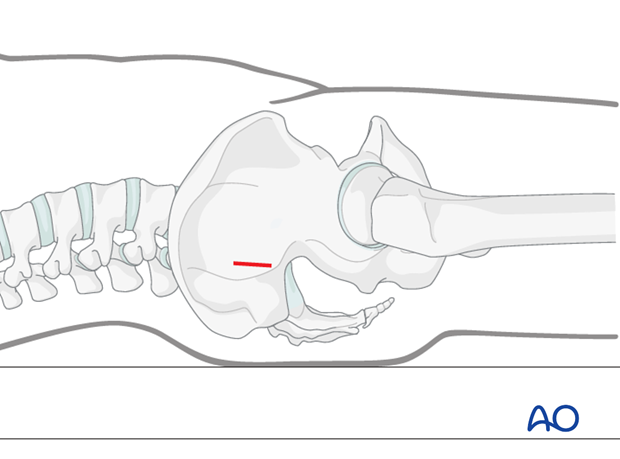

Landmarks for stab incision

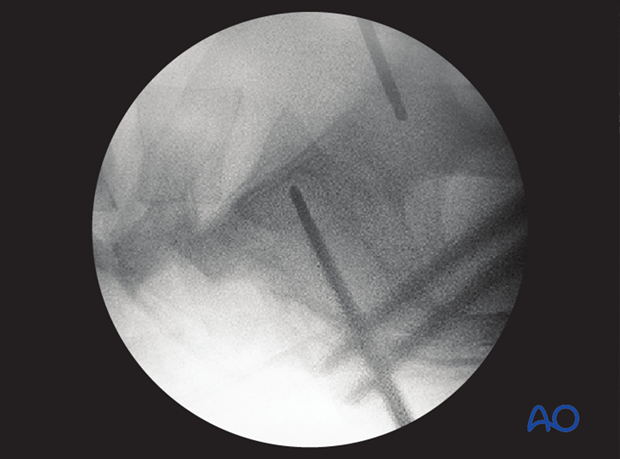

On the true lateral projection, identify the S1 body and iliac cortical densities (ICDs), here overlapping correctly.

If double contours of the iliac cortical densities (ICDs) are visible, as shown here, it is likely that the radiographic central ray is striking the pelvis obliquely. The C-arm should be adjusted to obtain a true lateral view, with superimposed ICDs and S1 cortices.

(This assumes that inlet and outlet views show that the pelvic reduction is anatomical.)

Location of screw entry point

The entry point should be anterior in S1 and inferior to the iliac cortical density (ICD), which parallels the sacral alar slope, usually slightly caudal and posterior. The ICD thus marks the anterosuperior boundary of the safe zone for an iliosacral screw which may injure the L5 nerve root if it penetrates this cortex.

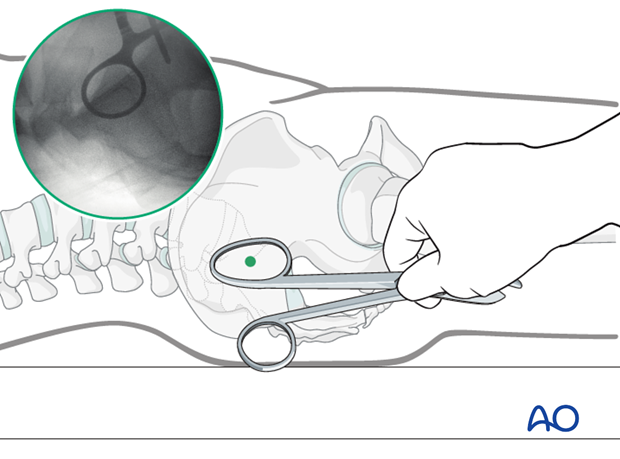

An instrument handle can help to target the desired entry site for the guidewire.

Incision

A stab incision is made at the identified site. The underlying tissues are dissected down to bone, by spreading with an appropriate blunt clamp, or with scissors if necessary.

There should be sufficient room for a protective drill sleeve, and for the planned screw and washer.

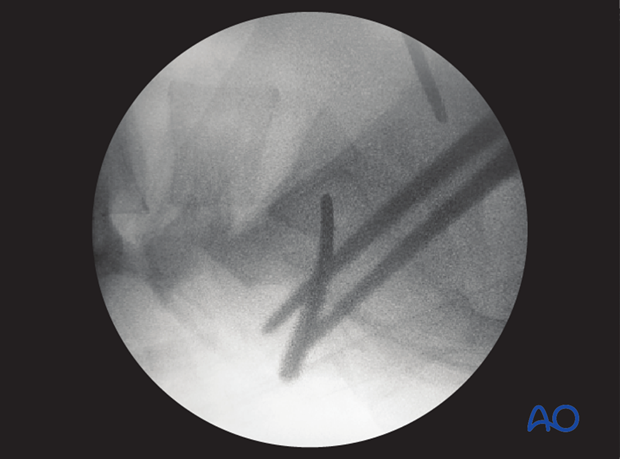

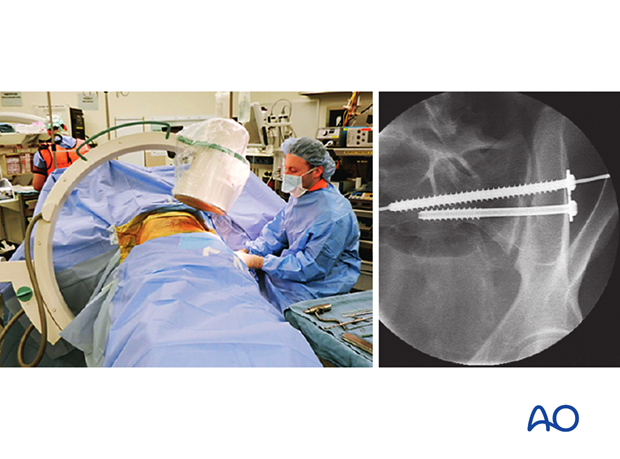

Guidewire insertion

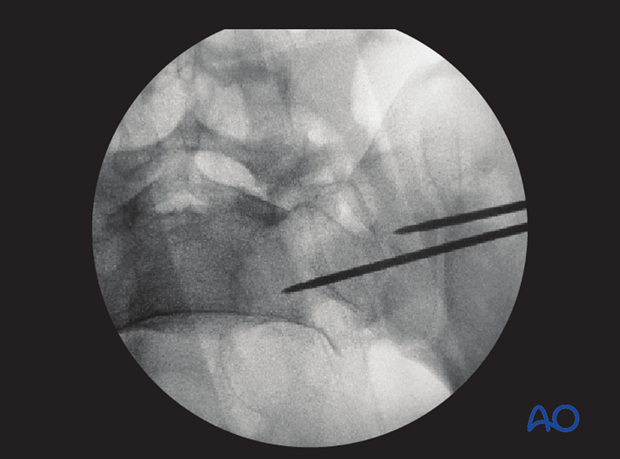

A guidewire is tapped 2-3 mm, or drilled (oscillating mode preferred) into the planned screw entry point. This is monitored by X-ray on the true lateral projection.

Note that with a true lateral view, the power source and chuck must be removed from guidewire or drill to assess their position.

The guidewire is advanced 1 cm into the sacral ala according to chosen screw channel.

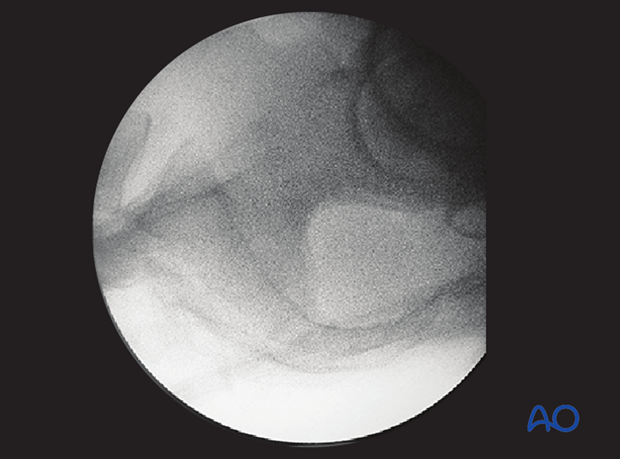

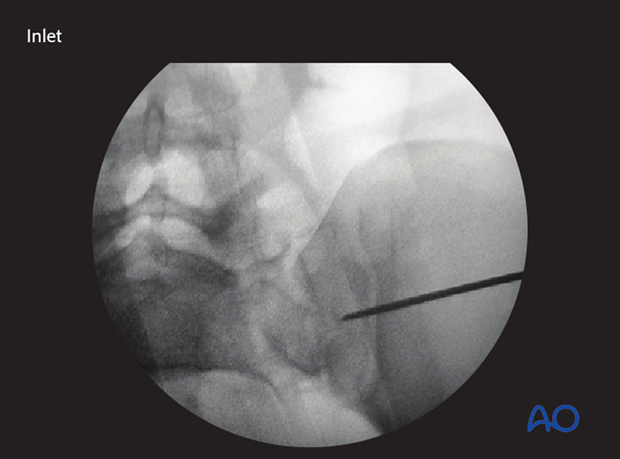

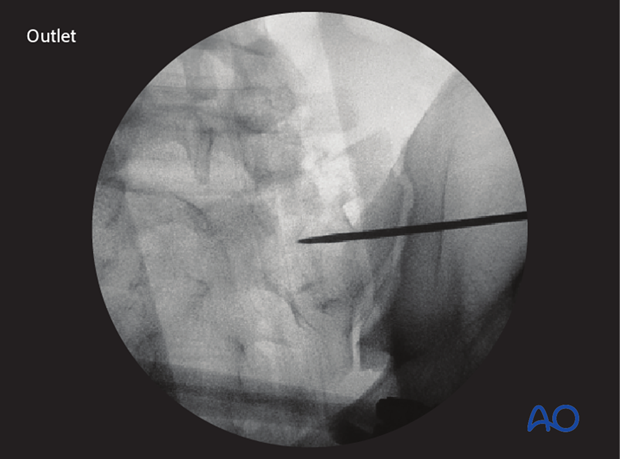

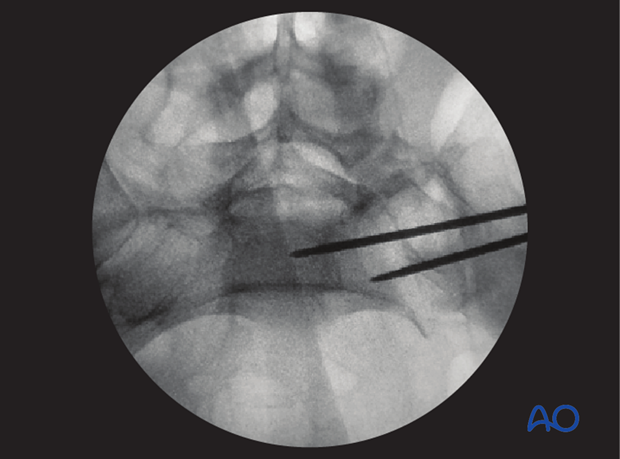

The position and trajectory of the guidewire is checked in inlet and…

…outlet projection.

When the guidewire tip is just lateral to the neural foramen on the outlet view, pause to confirm that its position is satisfactory.

The desired trajectory is within but close to the anterior alar cortex on the inlet view, and cranial to the ventral foramen of the 1st sacral nerve root.

If the trajectory of the guidewire would compromise either the sacral foramen or the spinal canal, the guidewire is removed and then reinserted from a similar entry point but in the corrected trajectory.

Alternatively, the guidewire is left in place as a reference and a new one is inserted along the correct trajectory.

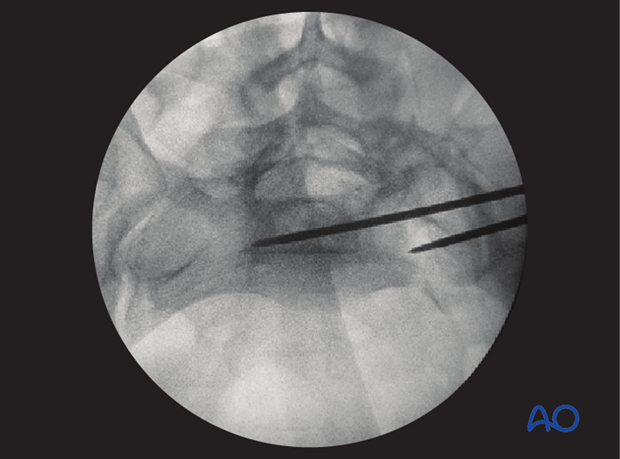

When a safe trajectory for the guidewire is confirmed, it is further advanced to the contralateral lateral border of the first sacral body.

When the guide wire reaches the center of the sacral body, the position is again verified in true lateral, inlet, and outlet view.

The wire must be far enough from cortices and neural foramina to accommodate the thread diameter of the planned screw.

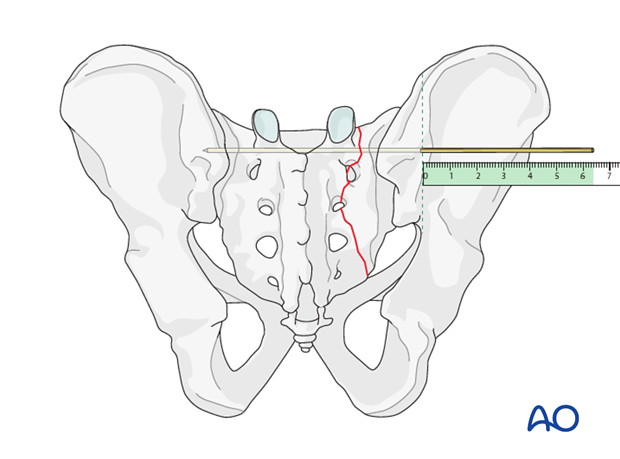

Screw insertion

The screw length is measured with a ruler or gauge suitable for the guidewire, and compared with the pre-operatively estimated length.

An appropriate screw hole is drilled over the guidewire, which should remain anchored in the bone, if it has been advanced far enough beyond the intended screw tip site.

The chosen cannulated lag screw is inserted with a washer.

In case of comminution, fully threaded screws may be preferred to avoid over-compression of a sacral fracture. They may also be used to supplement an initial lag screw.

The guidewire is removed.

Pifall: Intrusion of screw head into illium

Excessive tightening of the screw will cause intrusion of the screw head into the ilium.

Such errors, which compromise fixation, are more likely with osteoporotic bone.

To help prevent such intrusion, use of a washer should be routine.

With the C-arm rotated so its central ray is tangential to the ilium at the ISS insertion site, an excellent view of bone surface, washer, and screw head is available. This permits precise tightening of the screw without intrusion of washer and screw head through the iliac cortex.

8. Check of osteosynthesis

Upon completion of the ISS procedure, use multiple C-arm images to assess

- Reduction of sacral fracture

- Over-all pelvic ring alignment & symmetry

- Position of each screw, within cortical boundaries, and avoiding intra-osseous neural pathways

- Confirm that all guidewires and reduction aids have been removed

- Alignment and fixation of any associated ring injuries

Assessment of ISS requires AP, Inlet, outlet, and true lateral images of the posterior pelvis. Especially for bilateral injuries (B3, C2, and C3) radiographs that show the entire pelvic ring are necessary to confirm correction of complex deformities.

Make sure that any additional injury sites have been treated as planned.

9. Aftercare following open reduction and fixation

Postoperative blood test

After pelvic surgery, routine hemoglobin and electrolyte check out should be performed the first day after surgery and corrected if necessary.

Bowel function and food

After extensile approaches in the anterior pelvis, the bowel function may be temporarily compromised. This temporary paralytic ileus generally does not need specific treatment beyond withholding food and drink until bowel function recovers.

Analgesics

Adequate analgesia is important. Non pharmacologic pain management should be considered as well (eg. local cooling and psychological support).

Anticoagulation

Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus is routine unless contraindicated. The optimal duration of DVT prophylaxis in this setting remains unproven, but in general it should be continued until the patient can actively walk (typically 4-6 weeks).

Drains

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Wound dressing

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Physiotherapy

The following guidelines regarding physiotherapy must be adapted to the individual patient and injury.

It is important that the surgeon decide how much mechanical loading is appropriate for each patient's pelvic ring fixation. This must be communicated to physical therapy and nursing staff.

For all patients, proper respiratory physiotherapy can help to prevent pulmonary complications and is highly recommended.

Upper extremity and bed mobility exercises should begin as soon as possible, with protection against pelvic loading as necessary.

Mobilization can usually begin the day after surgery unless significant instability is present.

Generally, the patient can start to sit the first day after surgery and begin passive and active assisted exercises.

For unilateral injuries, gait training with a walking frame or crutches can begin as soon as the patient is able to stand with limited weight bearing on the unstable side.

In unstable unilateral pelvic injuries, weight bearing on the injured side should be limited to "touch down" (weight of leg). Assistance with leg lifting in transfers may be necessary.

Progressive weight bearing can begin according to anticipated healing. Significant weight bearing is usually possible by 6 week but use of crutches may need to be continued for three months. It should remembered that pelvic fractures usually heal within 6-8 weeks, but that primarily ligamentous injuries may need longer protection (3-4 months).

Fracture healing and pelvic alignment are monitored by regular X-rays every 4-6 weeks until healing is complete.

Bilateral unstable pelvic fractures

Extra precautions are necessary for patients with bilaterally unstable pelvic fractures. Physiotherapy of the torso and upper extremity should begin as soon as possible. This enables these patients to become independent in transfer from bed to chair. For the first few weeks, wheelchair ambulation may be necessary. After 3-4 weeks walking exercises in a swimming pool are started.

After 6 weeks, if pain allows, the patient can start walking with a three point gait, with less weight bearing on the more unstable side.

Full weight bearing is possible after complete healing of the bony or ligamentous legions, typically not before 12 weeks.