Nonoperative treatment

1. General considerations

Nonoperative treatment works well with the aid of ligamentotaxis in most humeral shaft fractures without significant initial displacement. Fractures will heal typically within three months.

Initially immobilize the arm in a splint and close to the chest to minimize pain. As pain subsides physiotherapy may be started in a functional brace.

Proximal and distal shaft fractures are not suitable for bracing. Due to the anatomy of the axilla, proximally the brace is not able to immobilize the proximal fragment. Distally, the brace may require an extension to the elbow joint with the risk of elbow stiffness.

Malalignment

There is a tendency for varus malalignment, particularly in obese patients. This may be countered by splint molding and arm positioning. Similarly, there is a risk of internal rotation malposition, which can be minimized by active arm use.

Healing with slight deformity does not usually cause a problem. Angulation and malrotation of 20-30° and shortening of up to 3 cm have been described as acceptable. Particularly in slender patients, this much angulation may cause visible deformity. This can be assessed during the healing process by physical examination.

2. Initial treatment

Reduction

Simple gravitational realignment of the fractured humerus is usually sufficient. With the patient upright and the limb hanging free, deformity is largely corrected by ligamentotaxis. Muscle forces may cause angulation, but, as the patient relaxes and becomes more comfortable, these forces diminish, and alignment improves. Manipulative reduction is rarely necessary.

Angulation can be improved with molding of the splint, as required.

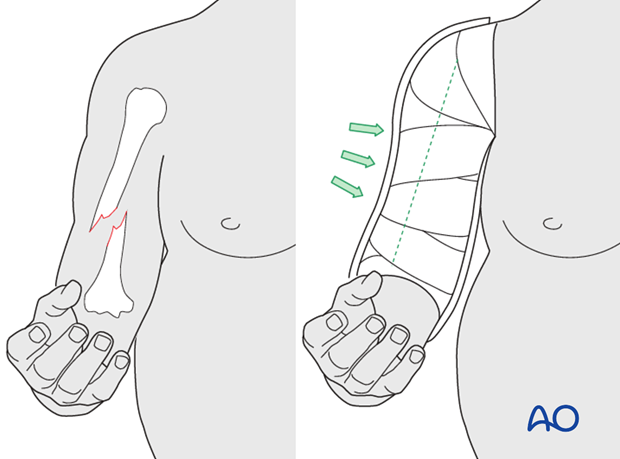

Cast padding

With the patient sitting, if possible, and leaning slightly to the injured side, wrap cast padding around the upper arm from axilla to elbow. Make sure that the epicondyles of the humerus and antecubital area are well padded.

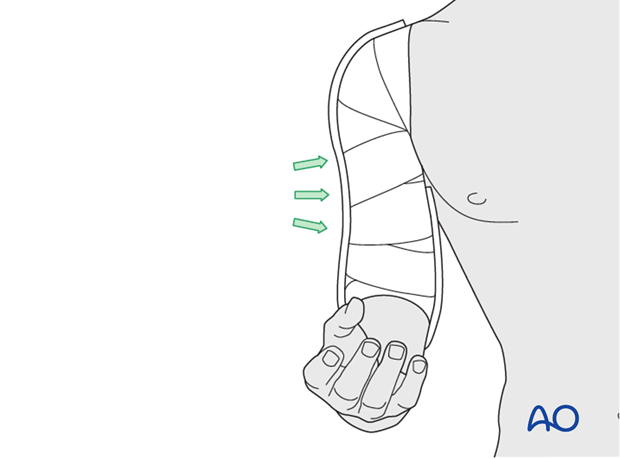

Application of splint

Apply a splint of fiberglass, or plaster, in a U-shape, with padding under the axilla. Wrap it from medial to lateral and over the shoulder (except for very distal fractures). Secure it in place with an elastic bandage that should not be too tight.

Mold this splint to be concave laterally, to correct typical varus angulation, especially in obese patients. The upper arm should appear straight when viewed from the side.

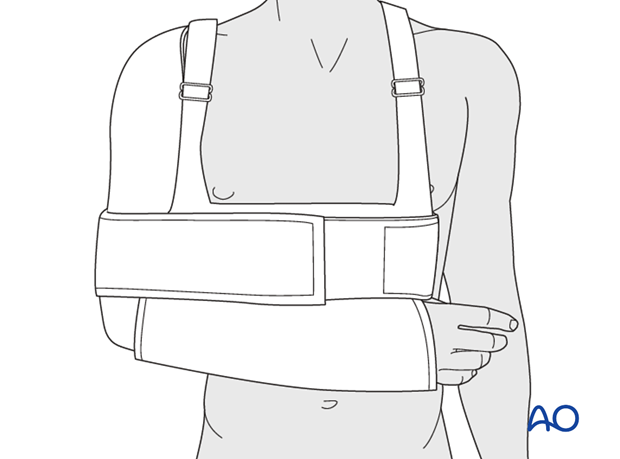

Securing injured arm

Secure the injured arm to the chest with a sling and swathe, shoulder immobilizer, or Velpeau bandage. If there is a radial nerve palsy, add a short arm splint to support the wrist in dorsiflexion.

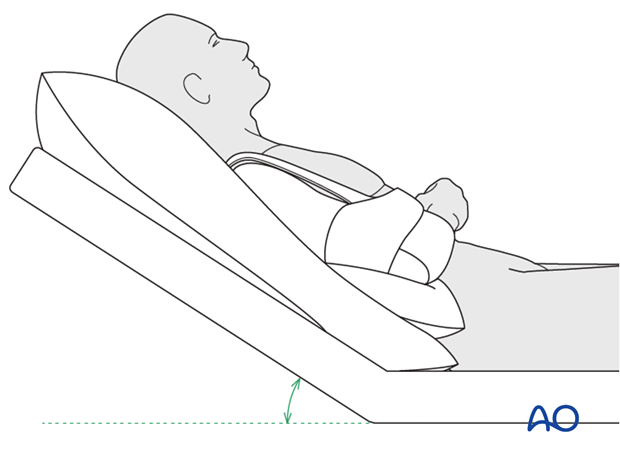

Pitfall: Internal malrotation

In highly instable fractures (grossly displaced or comminuted) securing of the injured arm to the chest may produce an internal malrotation of the humerus since the forearm internally rotates the distal humerus, while the shoulder muscles tend to hold the humerus in neutral position. In these cases, either try to fix the arm in neutral position (ie 15° external rotation of the flexed forearm using a shoulder abduction pillow) or consider surgical fixation.

Analgesia

Analgesia will be required. The patient is usually more comfortable in a sitting or semireclining position, at least for the first few weeks. Motion and crepitus will be felt, and the patient should be reassured that this is normal, stimulates healing and will gradually diminish.

Caution: soft-tissue care

Occasionally, a fracture that is initially closed may become open from excessive motion or splint pressure over a prominent fracture fragment. This will require immediate change to open management with debridement and fixation.

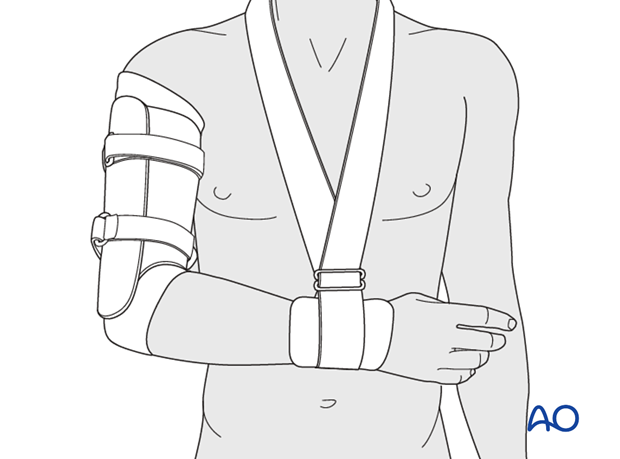

3. Fracture brace management

When the patient is comfortable, and the initial swelling has decreased, the temporary splint should be replaced with a prefabricated humeral fracture brace. The size should be chosen to fit the patient. Alternatively, if the services of an orthotist are available, a custom brace can be made.

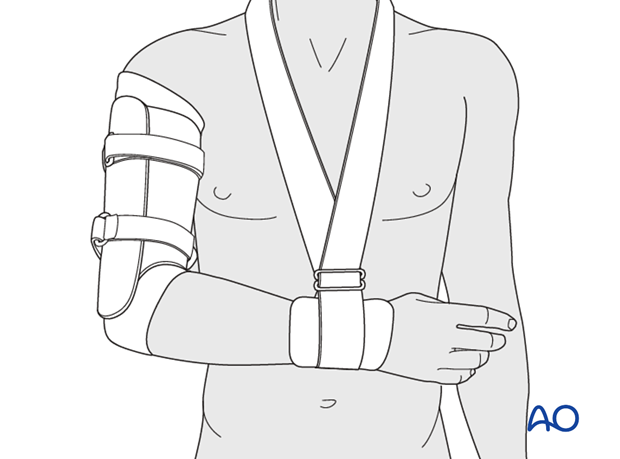

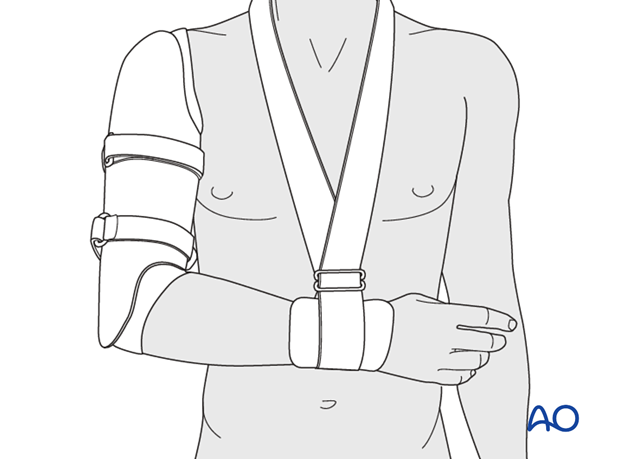

Brace types

This brace is a simple molded cuff that extends from axilla to elbow. Its straps can be tightened to provide containment support, but not true immobilization, for the fracture. This is only suitable for more distal fractures.

This brace extends over the shoulder and may provide somewhat better support for more proximal fractures. However, it may also prove irritating during shoulder motion.

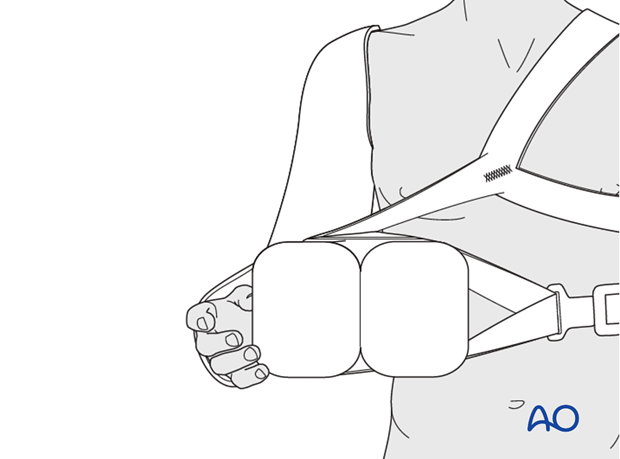

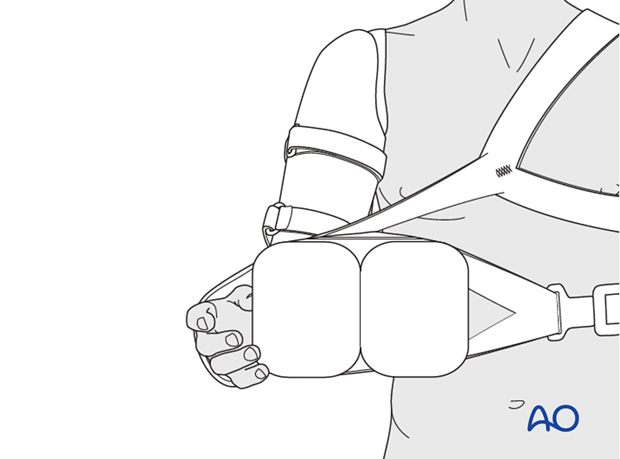

If there is a varus tendency, the arm can be supported away from the body with a pad (“shoulder abduction pillow”) under the medial side of the elbow, as shown. This support can be quite helpful for obese patients.

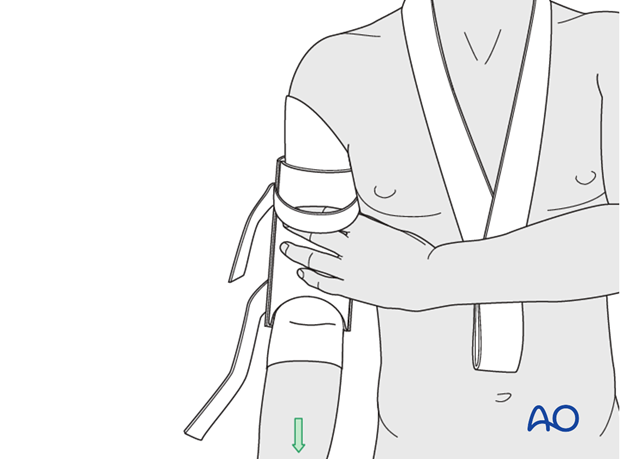

Brace application

Apply padded stocking, or sleeve, first to the upper arm, stabilizing the fracture as necessary with gentle distal traction.

Position the brace to avoid pressure in the antecubital fossa, or the axilla. It should be applied with correct rotation.

Initially, the patient may be more comfortable if the arm remains supported with the sling and swathe.

4. Aftercare

Initial mobilization

As soon as possible, the sling should be discontinued. A collar and cuff may often be substituted before the unsupported arm is comfortable. Use of the arm, while avoiding abduction from the chest, is to be encouraged. Abduction is painful until healing is advanced and provokes varus deformity. It is also good to encourage external rotation at the shoulder, but not at the fracture site.

Brace care

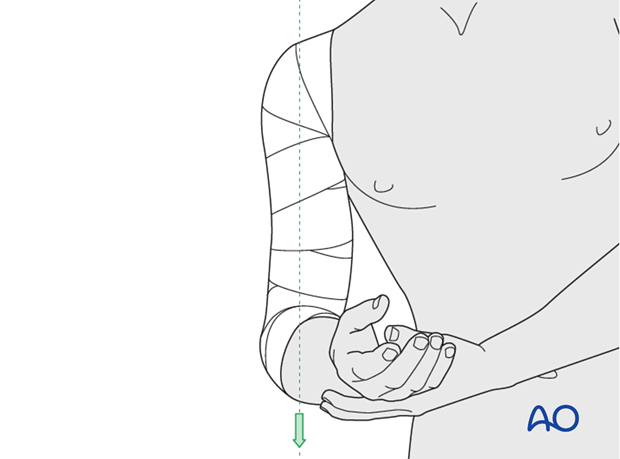

As soon as comfort permits, the patient must be instructed in donning and removing the brace and caring for the underlying skin.

By letting the arm hang straight down, the patient stabilizes the unbraced fracture with the force of gravity and regains elbow extension. In this position he is able to shower, wash the arm, and replace the stocking with a clean one, usually daily.

The patient must learn to position the brace correctly. It must be high enough to allow elbow flexion. Because the brace tends to slide down the arm, he may need to reposition it periodically during the day. Rotational position of the brace is also important. The patient should be taught to position the brace so that its anterior inferior edge accommodates the proximal forearm during elbow flexion. The longer medial and lateral sides of the brace’s distal end should overlie the humeral epicondyles.

Mobilization

Simultaneous isometric contraction of flexors and extensors is important, as it stimulates fracture healing, improves support of the fracture inside the brace, and corrects fracture distraction produced by the weight of the distal arm. This can begin quite soon.

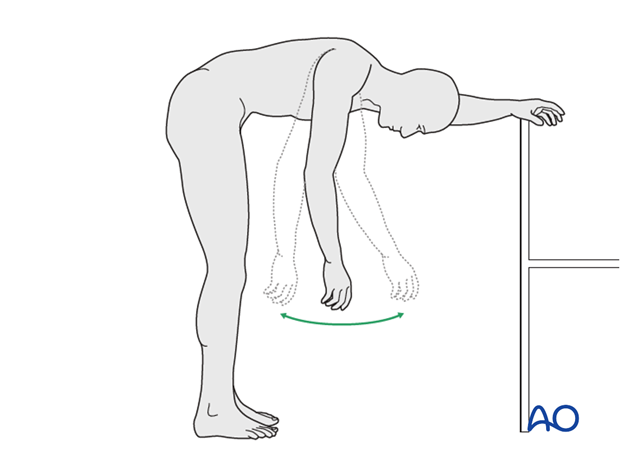

As soon as possible, begin pendulum exercises for passive shoulder flexion. Encourage active use of the hand and forearm.

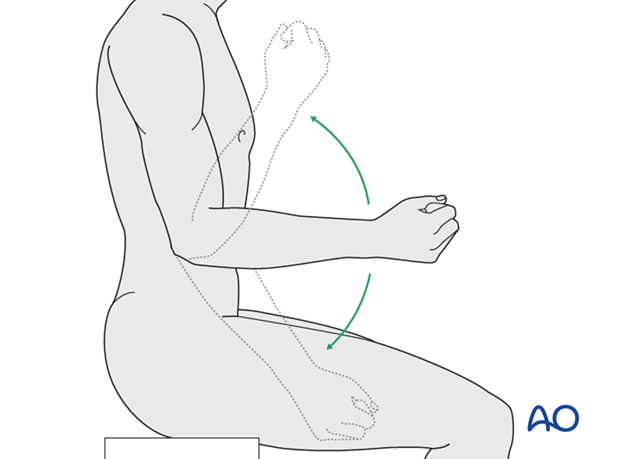

Try to regain active elbow flexion as soon as comfortable. Gravity should be allowed to help with elbow extension.

Patient monitoring

Early after injury, the patient will need to be seen every week or two to ensure satisfactory splint or brace position. Adequacy of analgesia must be assessed with adjustment of medication as needed. Check the skin under the brace, particularly around the elbow, for irritation. Confirm that the patient has learned to remove and replace the brace correctly. Home health care assistance may be necessary, possibly including physical therapy at home, until the patient is independent in self-care and use of the arm.

As healing progresses, upper extremity function is also encouraged.

Healing assessment

Check x-rays are obtained at three and six weeks and thereafter monthly unless there is earlier concern about malalignment. Usually, progressive callus will be observed. The arm should be examined out of the brace. Stability of the fracture will become increasingly evident, and pain will diminish. When active abduction of the shoulder to 90° is possible without pain, or evident motion at the fracture, the brace may be discontinued. The patient may be comfortable sleeping without the brace before this, but its daytime use may be appropriately advised. Progressive resistance exercises and assisted shoulder motion can begin vigorously at this time.

Caution about risk activities and contact sports remains advisable until mature callus is visible and full strength and motion have been restored.

Delayed union

Healing is usually evident by three months. Occasionally at three months the fracture remains mobile to a degree, yet convincing clinical progress is observed, and healing at a slightly later date is to be anticipated. Generally, however, failure to unite by three months is strong evidence that union is unlikely to occur without a change of treatment. Operative stabilization, with possible bone graft, is recommended without prolonged delay.

Radial nerve palsy - prevent contractures

Since radial nerve injuries with humeral fractures usually recover, nonoperative fracture management is often appropriate for patients with these combined injuries. It is important to include physical therapy and splinting for the hand to avoid wrist flexion and thumb adduction contractures and to maintain metacarpo-phalangeal extension. The nerve is observed for progressive motor and sensory recovery. The former typically begins with return of brachioradialis and the radial wrist extensors. Finger extension and thumb abduction will follow. Electrodiagnostic testing might be considered at six weeks, if there is no clinical evidence of recovery at that time.

If there are no clinical and electromyographic signs of recovery at three months, consider surgical exploration and neurolysis of the radial nerve at the fracture site.