Nonoperative treatment

1. General considerations

Indications

Undisplaced or minimally displaced diaphyseal and stable extraarticular fractures can be treated nonoperatively with splinting.

Most of these fractures produce an extension deformity and minimal shortening. Any malrotation and more than 2 mm shortening cannot be accepted, and operative treatment is recommended.

Irreducible rotational malalignment is an indication for operative treatment.

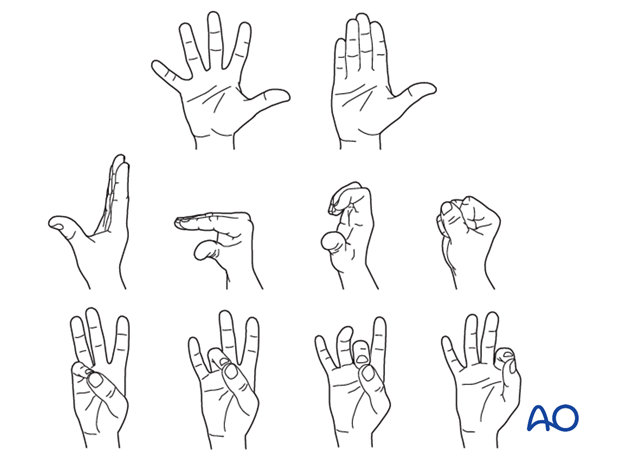

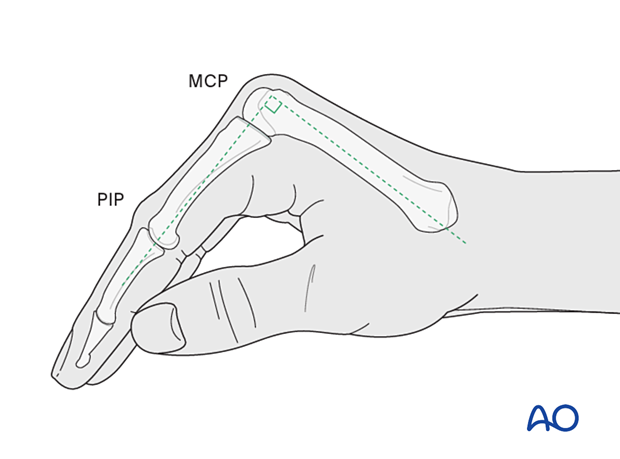

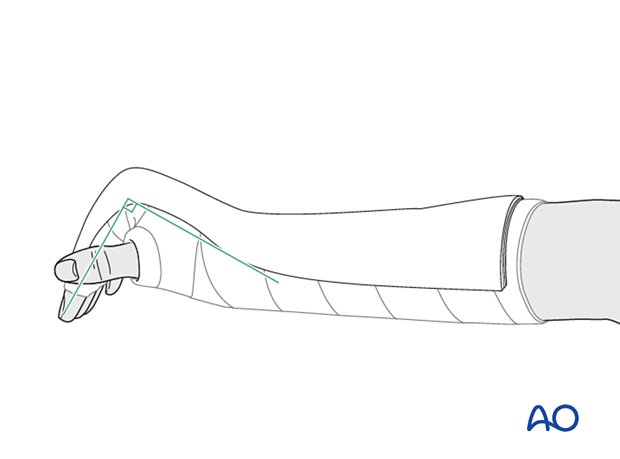

Hand position for splinting

The hand should be splinted in an intrinsic plus (Edinburgh) position:

- Neutral wrist position or up to 15° extension

- Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint in 90° flexion

- Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint in extension

The reason for splinting the MCP joint in flexion is to maintain its collateral ligament at maximal length, avoiding scar contraction.

PIP joint extension in this position also maintains the length of the volar plate.

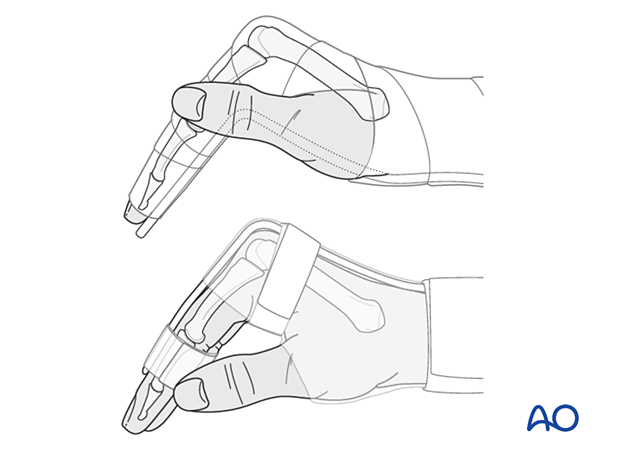

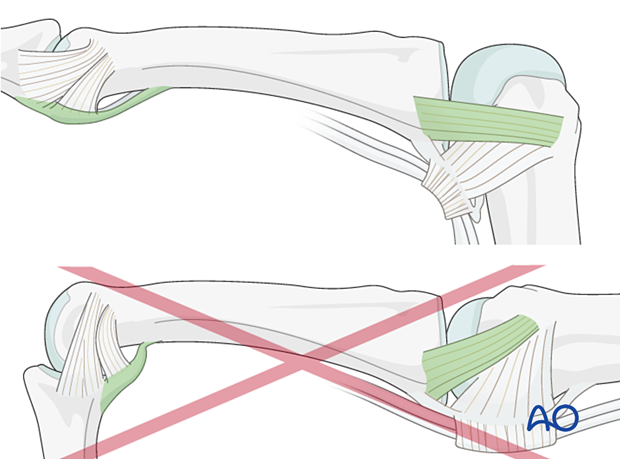

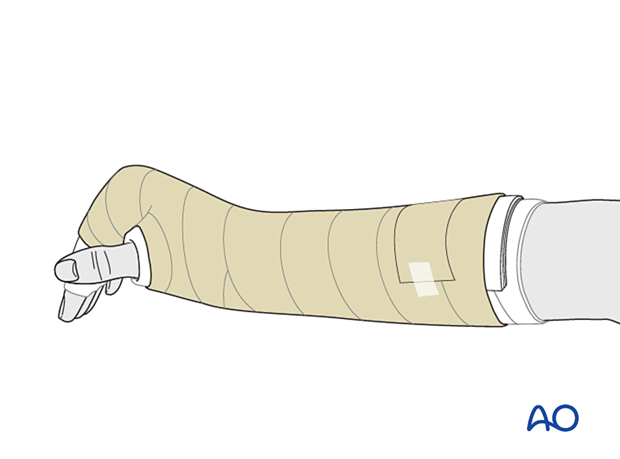

Palmar vs dorsal splint

Both splints are easy to apply and there is no need for hand therapy.

A potential disadvantage of the palmar splint is the complete immobilization of uninjured fingers and joints. The MCP joint may not be in the optimal 90° flexion, which may lead to loss of motion.

The dorsal splint allows immediate active mobilization (flexion) of the finger joints.

AO teaching video

Phalanx–Proximal Fractures–Extension Block Splint (Burke Halter)

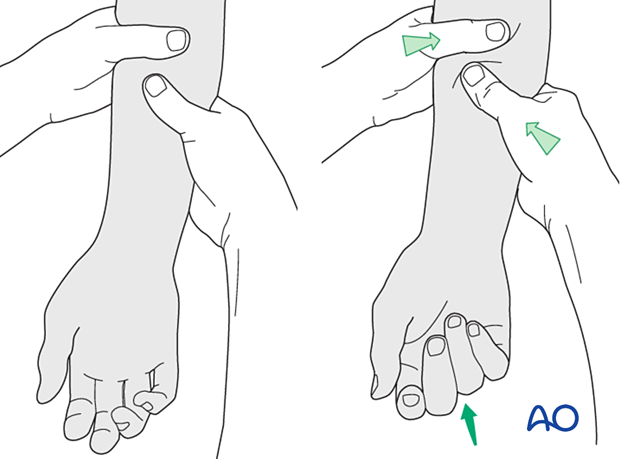

2. Reduction

Displacement usually occurs as an extension deformity.

For reduction, apply longitudinal traction to the finger and flex the MCP joint.

Also, correct any rotational malalignment.

Any lateral angulation can be checked by comparison with the adjacent fingers and must be reduced.

Confirm angular reduction using image intensification.

3. Checking alignment

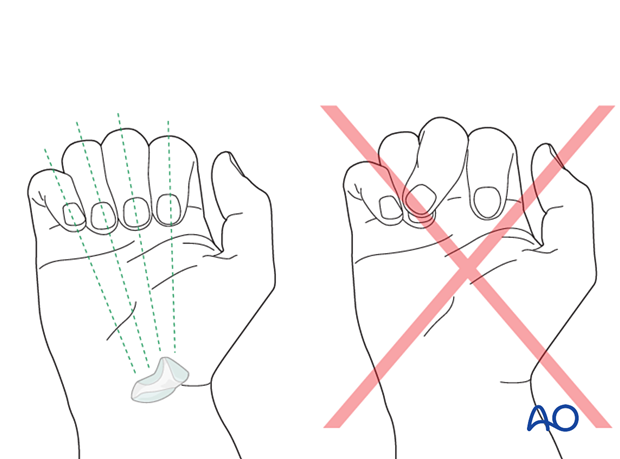

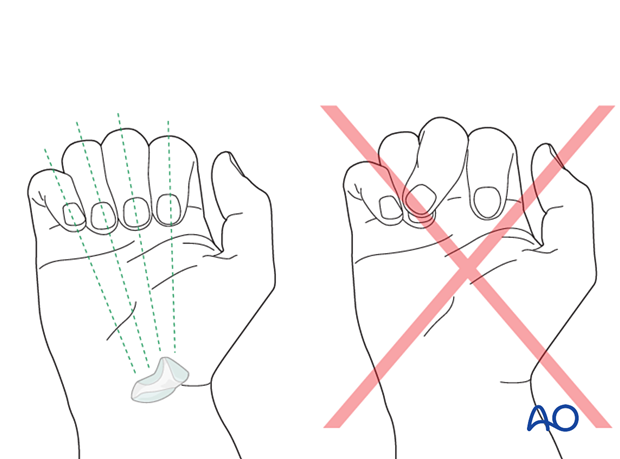

Identifying malrotation

At this stage, it is advisable to check the alignment and rotational correction by moving the finger through a range of motion.

Rotational alignment can only be judged with flexed metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. The fingertips should all point to the scaphoid.

Malrotation may manifest by an overlap of the flexed finger over its neighbor. Subtle rotational malalignments can often be judged by a tilt of the leading edge of the fingernail when the fingers are viewed end-on.

If the patient is conscious and the regional anesthesia still allows active movement, the patient can be asked to extend and flex the finger.

Any malrotation is corrected by direct manipulation and later fixed.

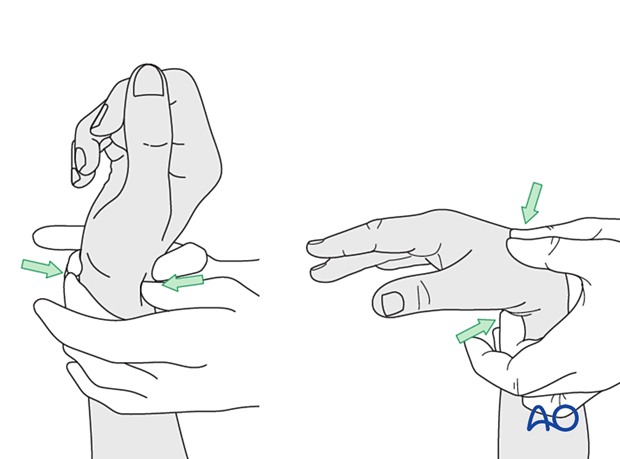

Using the tenodesis effect when under anesthesia

Under general anesthesia, the tenodesis effect is used, with the surgeon fully flexing the wrist to produce extension of the fingers and fully extending the wrist to cause flexion of the fingers.

Alternatively, the surgeon can exert pressure against the muscle bellies of the proximal forearm to cause passive flexion of the fingers.

4. Splint application

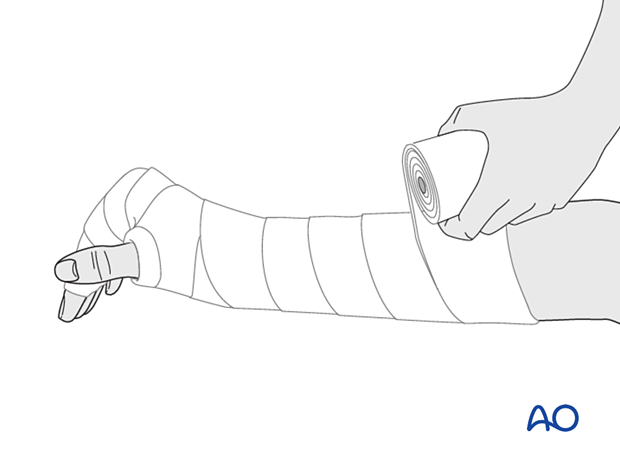

Protect the skin of the arm and hand with padding/cotton sleeve to avoid pressure sores, especially on the distal ulna and styloid process of the radius.

In compliant patients, only the affected and the directly neighboring fingers may be included in the splint.

Create a splint of at least 6 slabs of cast bandage. It should cover the dorsal or palmar half of the forearm, wrist, and hand.

The wrist should be in neutral or up to 15° extension.

The splint is held in place with an elastic bandage. The bandage should not be overtightened at the level of the wrist joint to avoid excessive swelling of the hand.

Direct skin contact with adjacent fingers should be prevented by placing gauze pads between them.

In a dorsal splint, buddy strap the injured finger to an adjacent finger.

5. Aftercare

Postoperative phases

The aftercare can be divided into four phases of healing:

- Inflammatory phase (week 1–3)

- Early repair phase (week 4–6)

- Late repair and early tissue remodeling phase (week 7–12)

- Remodeling and reintegration phase (week 13 onwards)

Full details on each phase can be found here.

Follow-up

X-ray checks of fracture position should be performed immediately after the splint has been applied.

Follow-up x-rays with the splint should be taken after 1 week and after 2 weeks if there is doubt about maintenance of reduction.

Splinting is continued until about 4 weeks after the injury. At that time, an x-ray without the splint is taken to confirm healing, and range of motion should be pain-free.

Mobilization

Splinting can then usually be discontinued, and active mobilization is initiated. Functional exercises are recommended.

If, after 8 weeks, x-rays confirm healing, full manual loading can be permitted.