Lag screw fixation

1. Principles

Indications

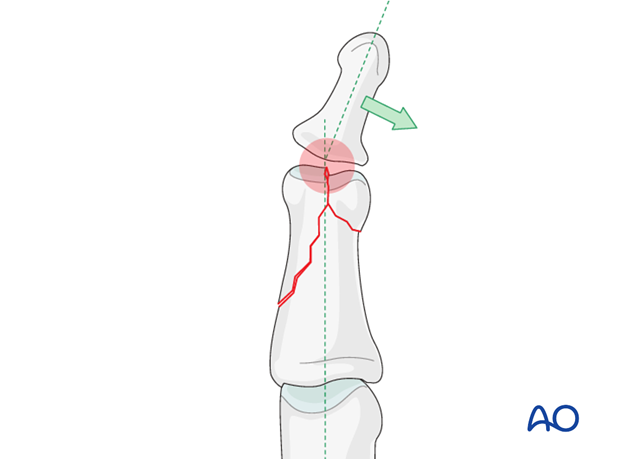

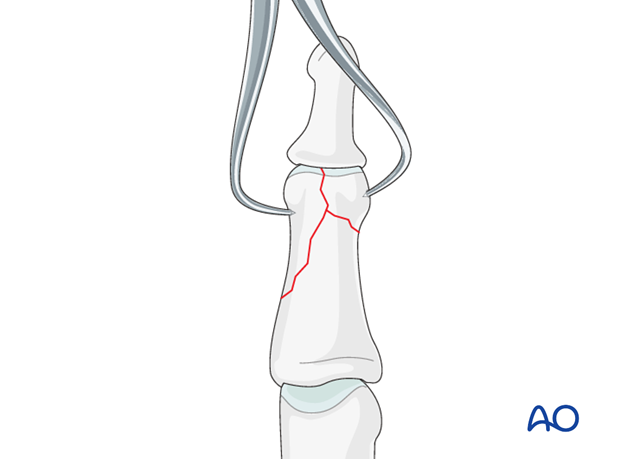

Bicondylar fractures of the head of the middle phalanx may be T-shaped, with a long, or a short, T.

Another pattern of fracture is a combination of a long oblique fracture separating one condyle, together with a short oblique, or transverse, fracture separating the other condyle (sometimes called “reversed lambda” fractures, because of their resemblance to the Greek letter “λ“).

Lag screw fixation is indicated both for the short T-shaped and the reversed lambda fractures.

Typically these fractures are the results of sports injuries, due to axial load combined with lateral angulation of the finger.

Condylar fractures tend to be very unstable and should be treated operatively. If conservative treatment is attempted, a secondary displacement is likely, leading to angulation of the finger.

Outcome of fractures of the middle phalanx is usually more favourable than in the proximal phalanx. This is largely due to the fact that limitations in DIP joint motion is not as great a problem as similar limitations in the PIP and MCP joints.

However, since fragments in this segment are generally smaller than in the proximal phalanx, management and stabilization can be more of a challenge.

Consequences of malunion (pain or deformity), or of degenerative joint disease, at the DIP joint can well be dealt with by arthrodesis, which is a procedure with very predictable outcome.

Caveat

These fractures are rare, but difficult to treat. There is an increased risk of joint stiffness resulting from these fractures.

It is wise to use magnifying loupes in these procedures. Gentle and precise handling throughout the procedure is mandatory.

K-wire fixation

Percutaneous K-wire fixation is often used for fractures of the middle phalanx.

The advantages are

- technically easy

- minimal soft-tissue lesion

- affordable cost

- universal availability

However, there are some disadvantages which can sometimes be significant, such as

- less stable fixation

- no compression possible

- no early mobility

- may separate the fragments

- may irritate the skin

Anatomical reduction recommended

Although the DIP joint is very forgiving, articular fractures should be reduced anatomically. Otherwise, the articular cartilage may be damaged, leading to painful degenerative joint disease and digital deformity. At the DIP joint, this can well be dealt with by arthrodesis, which is a procedure with very predictable outcome, without any major perturbances of the finger.

This illustration shows how even slight unicondylar depression may lead to angulation of the finger.

2. Planning

Approach

Carefully evaluate the x-rays.

The fracture will have to be approached from the side of the larger fragment through a midaxial approach to the middle phalanx.

Number of screws

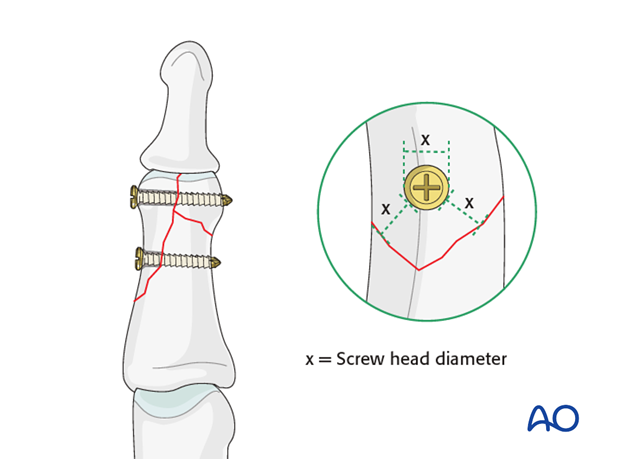

Ideally, 3 screws will be used to fix the larger fragment, although, more commonly, insertion of only 2 screws will be possible.

When planning for the screws, assess the fracture plane and the size of the fragments. Keep in mind that the larger fragment must be at least as long as twice the diameter of the diaphysis if screw fixation alone is to be used.

An important general rule is that the minimal distance of a screw head from the fragment apex must be at least the diameter of its head.

Position of the distal screw

The position of the distal screw depends on the geometry of the fracture line which separates the condyles, and the size of the smaller fragment. This screw has to be planned carefully.

Vertical fracture plane

If the intercondylar fracture line is vertical, the lag screw will have to be inserted transversely, distal to the attachment of the collateral ligament, in order to cross the intercondylar fracture plane as perpendicularly as possible, and to secure the small fragment.

Oblique fracture plane

If the intercondylar fracture line is oblique, and the smaller fragment is large enough, the distal lag screw will be inserted obliquely, perpendicular to the intercondylar fracture plane, its point of entry being proximal to the attachment of the collateral ligament, and extraarticular.

3. Reduction

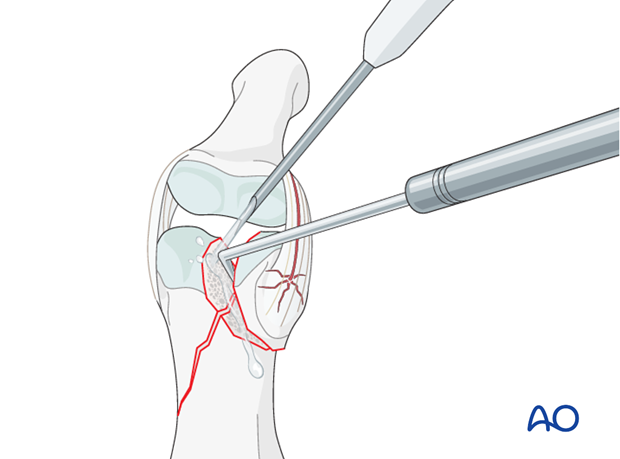

Visualization of the fracture

In order to gain a better view of the fracture, use a syringe to irrigate out blood clot with a jet of Ringer lactate.

Gently explore the fracture site to assess its geometry, using a dental pick. The pick can also be used carefully to reduce small fragments. Take great care to avoid comminution of any fragment.

It is important to maintain the vascularity of tiny fragments attached to the collateral ligament, in order to avoid osteonecrosis.

Indirect reduction

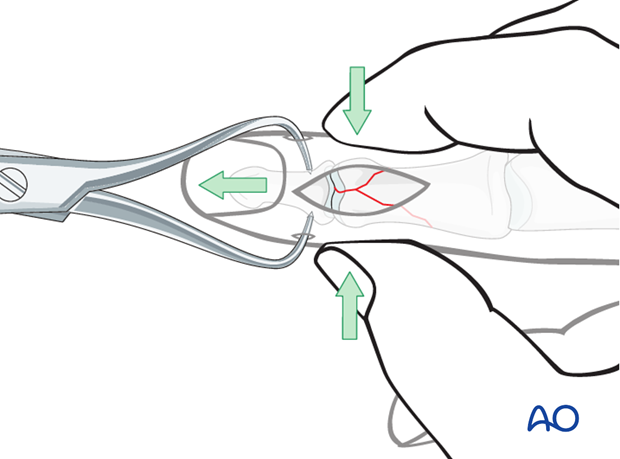

Reduction starts with traction in order to restore length.

Lateral pressure, exerted by the surgeon’s thumb and index finger, will then reduce the fracture.

Confirm reduction using image intensification.

Restore articular surface

A small pointed reduction forceps can be used for larger fragments gently to manipulate the fracture by rocking from side to side. Be careful not to apply excessive force as this can lead to fragmentation.

Confirm reduction using image intensification.

Note

Anatomical reduction is mandatory to prevent chronic instability or posttraumatic degenerative joint disease.

Small intraarticular defect

In some cases a small additional intraarticular fragment is present. This fragment can be excised, but its removal will preclude the use of a lag screw between the condyles.

4. Preliminary fixation

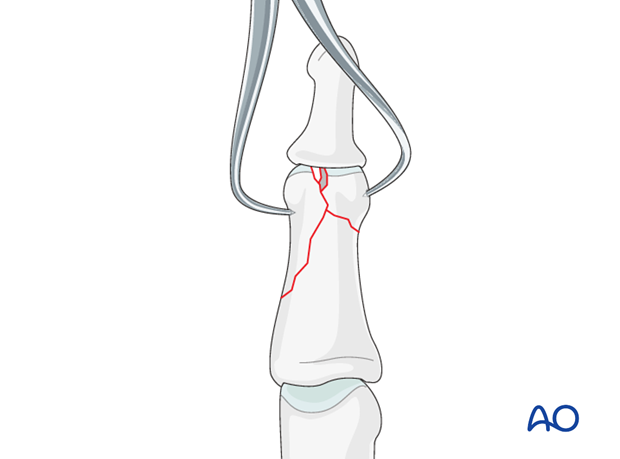

In reverse lambda fractures, the condyles are preliminarily fixed by inserting a 0.6 mm K-wire, just deep to the subchondral bone. Be careful to insert it in such a way that it will not conflict with later screw placement.

Avoid inserting a K-wire into very small fragments, as they are in danger of fragmentation.

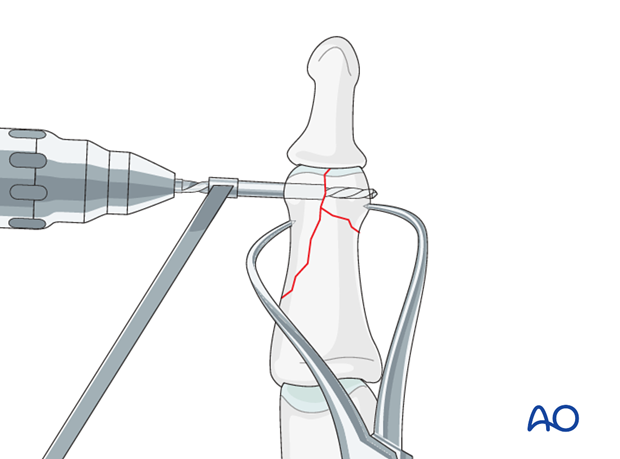

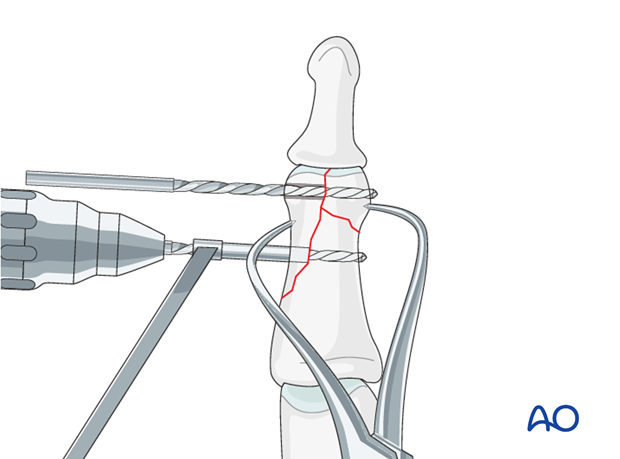

5. Drilling

Drilling and alternative preliminary fixation

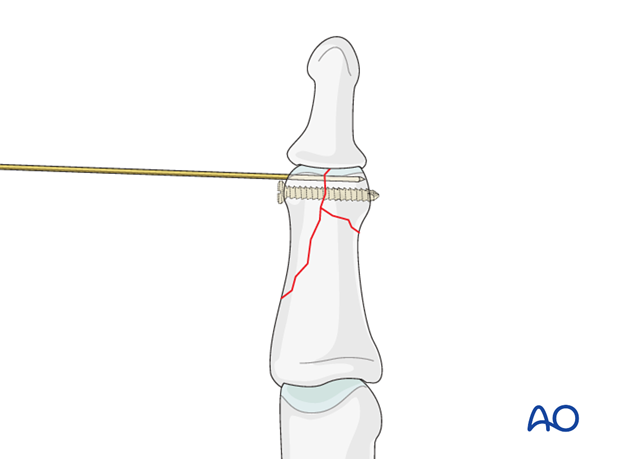

Leaving the reduction forceps in place, drill a gliding hole as perpendicularly to the intercondylar fracture plane as possible, using a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm drill bit for a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm screw. Insert a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm drill sleeve into the gliding hole.

Use a 1.0 (or 0.8) mm drill bit to drill a thread hole in the opposite fragment, just through the far (trans) cortex.

Leave the drill bit in situ as temporary fixation.

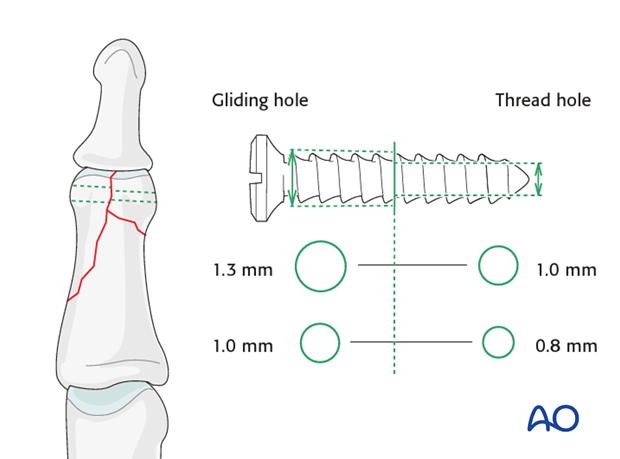

Screw size selection

The exact size of the diameter of the screw used will be determined by the fragment size and the fracture configuration.

The various gliding hole and thread hole drill sizes for different screws are illustrated here.

Screw length needs to be adequate for the screw just to penetrate the opposite cortex.

Keep in mind that at the apex of the fragment, the minimal distance between the screw head and the fracture line must be at least equal to the diameter of the screw head. If necessary, a screw of smaller diameter will have to be chosen.

Screw length

Use a depth gauge to determine the correct screw length.

Pitfalls

Ensure that a screw of the correct length is used.

Too short screws do not have enough threads to engage the cortex properly. This problem increases when self-tapping screws are used due to the geometry of their tip.

Too long screws endanger the soft tissues, especially tendons and neurovascular structures. With self-tapping screws, the cutting flutes are especially dangerous, and great care has to be taken that the flutes do not protrude beyond the cortical surface.

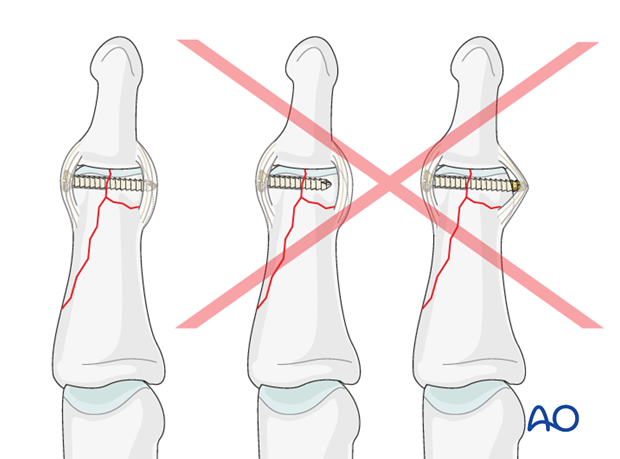

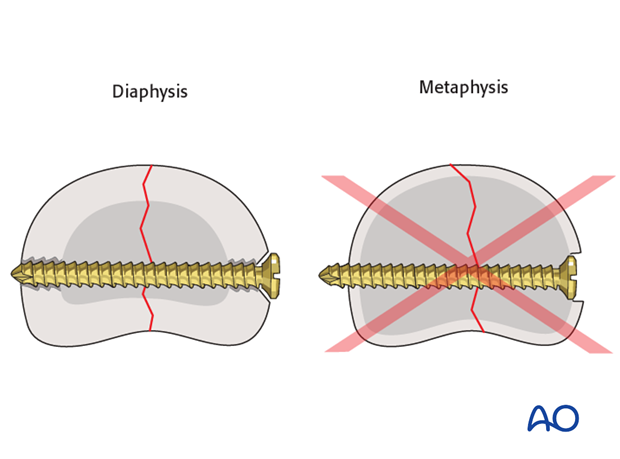

No countersinking in the metaphysis

Do not countersink the screws in the metaphysis as its cortex is very thin.

If countersinking is attempted, all purchase and compression may be lost due to screw-head breakthrough.

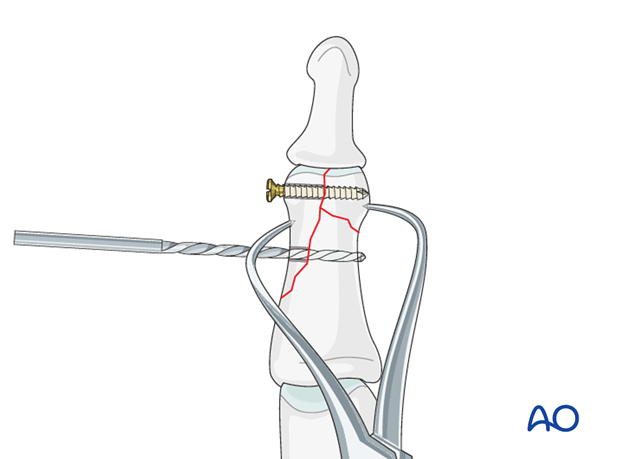

Drill for second screw

Towards the proximal apex of the fracture line, drill a gliding hole for a diaphyseal lag screw. This screw, too, should be placed as perpendicularly to the diaphyseal fracture plane as possible, using a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm drill bit for a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm screw. Insert a 1.3 (or 1.0) mm drill sleeve into the gliding hole.

Use a 1.0 (or 0.8) mm drill bit to drill a thread hole in the opposite fragment, just through the far (trans) cortex.

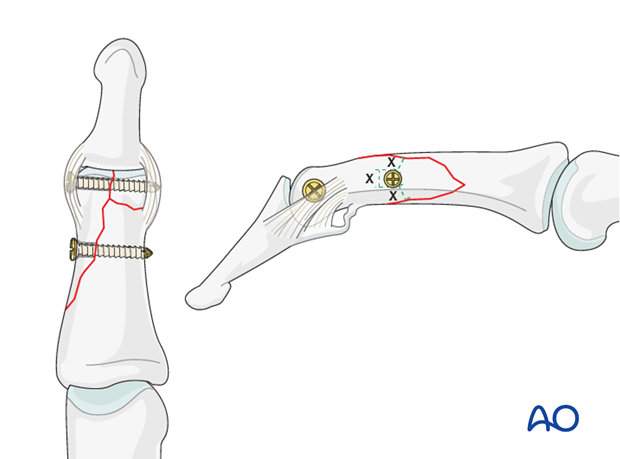

6. Fixation

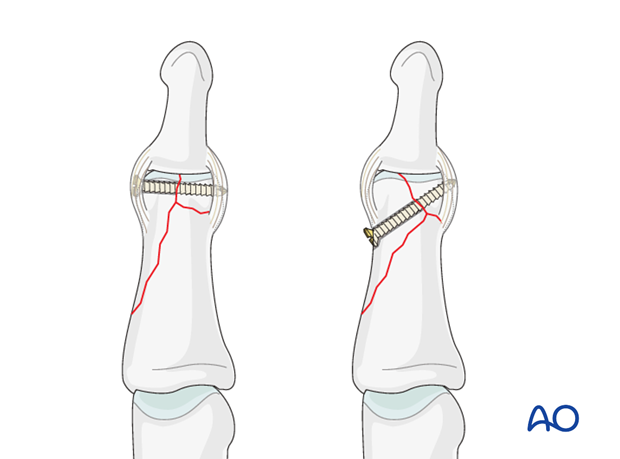

Insert first screw

Insert the distal lag screw. Do not completely tighten it at this time. The screw should just penetrate the opposite cortex.

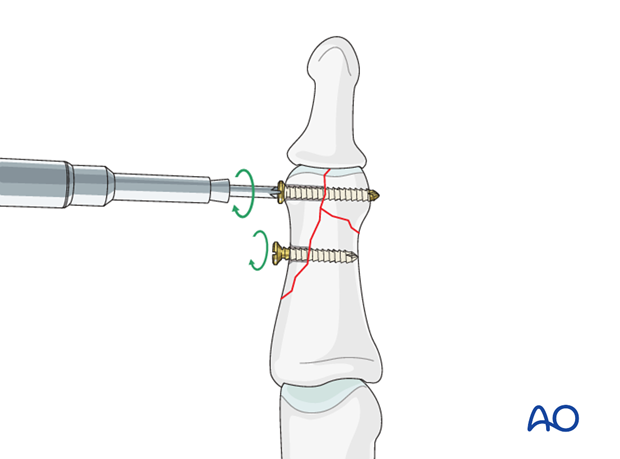

Insert second lag screw

Now insert the diaphyseal lag screw. This screw, too, should just engage the opposite cortex.

Alternate tightening of the two lag screws helps to avoid tilting of the fragment, and applies even compression forces across the whole fracture surface.

Check using image intensification. Reduction must be anatomical.

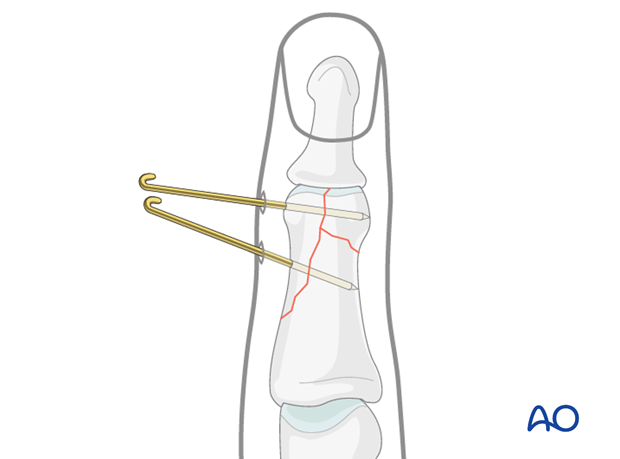

7. Alternative K-wire fixation

Percutaneous K-wire fixation can be an easy-to-perform and cost-efficient alternative to lag screw fixation. However, the disadvantages of K-wire fixation remain, most notably less stability, lacking compression and the risk of displacement.

For K-wire fixation, introduce 2 unthreaded K-wires percutaneously, ensuring that they cross the fracture plane as perpendicularly as possible. To reduce the risk of displacement, insert the K-wires at diverging angles.

Confirm reduction using image intensification.

Cut the K-wire outside of the skin and bend them.

8. Aftertreatment

Postoperatively

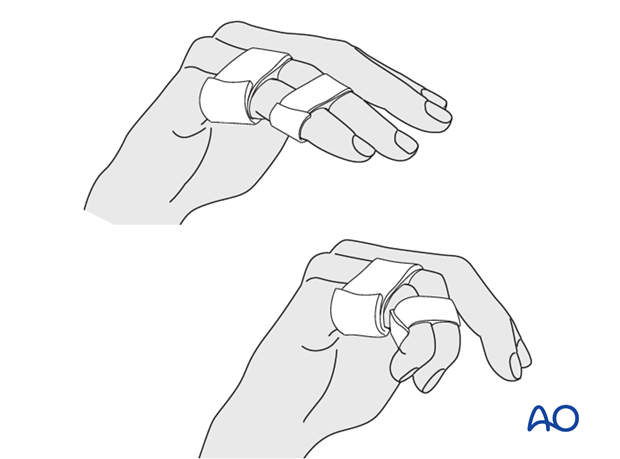

Protect the digit with buddy strapping to the adjacent finger, to neutralize lateral forces on the finger.

While the patient is in bed, use pillows to keep the hand elevated above the level of the heart to reduce swelling.

After K-wire fixation

After K-wire fixation, the DIP joint has to be immobilized in extension, leaving the PIP joint free. Either an alumaform splint, or a custom-made thermoplastic splint can be used.

Remove K-wires after 3 weeks, keeping the splint for an additional 2 weeks.

Follow up

See the patient 5 days and 10 days after surgery.

Functional exercises

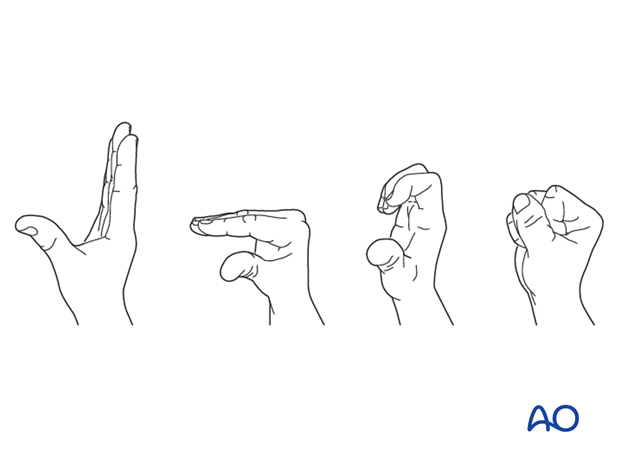

The patient can begin active motion (flexion and extension) immediately after surgery.

For ambulant patients, put the arm in a sling and elevate to heart level.

Instruct the patient to lift the hand regularly overhead, in order to mobilize the shoulder and elbow joints.

Implant removal

The implants may need to be removed in cases of soft-tissue irritation.

In case of joint stiffness, or tendon adhesion’s restricting finger movement, tenolysis, or arthrolysis become necessary. In these circumstances, take the opportunity to remove the implants.