Ligament injuries of the hand

1. General considerations

The management of associated ligament injuries of the hand is described with the treatments of respective injury types.

Here, general management principles of ligament injuries are presented.

2. Clinical assessment

A thorough history and physical exam are critical to properly assess hand ligament injuries. Considerations include:

- Mechanism of injury

- Location of pain and tenderness

- Presence of deformity or instability

- Loss of function

3. Imaging

Imaging studies can aid in diagnosis and classification of ligament tears.

- Plain x-rays assess fractures and dislocations which may be associated with predictable ligament injuries. Stress views may be useful to assess laxity. Local anesthetic infiltration can facilitate stress views.

- An MRI improves a diagnosis of ligament tears and helps to classify severity. MRI with arthrography is helpful in the diagnosis of intrinsic injuries, eg, the partial scapholunate ligament rupture.

- Ultrasound allows dynamic assessment of ligament integrity and related articular movement.

4. Diagnosis

Ligament injuries may be classified by location (eg, collateral ligaments, volar plate) or grade of tear (partial vs complete). Pathoanatomic classification guides treatment.

5. Principles of management

Incomplete ligament injuries often do not need specific surgical management and heal well with protective splinting and progressive rehabilitation.

In case of complete ligament injuries resulting in important instability, eg, complete scapholunate disruption or skier’s thumb, surgery could be considered.

6. Healing and rehabilitation

Early protected motion is beneficial to prevent stiffness and promote healing after ligament repair. Splinting or bracing may be used initially to protect the repair.

Hand therapy focuses on controlling edema, regaining range of movement, proprioception, and later strengthening to restore function.

For details on postoperative treatment phases, see the dedicated pages in each anatomical section.

7. Specific injuries

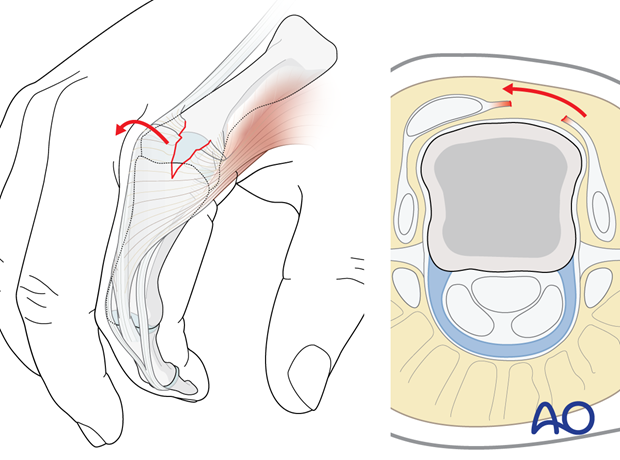

Sagittal band injuries

Sagittal band injuries at the MCP joint cause imbalance of the extensor tendons with subsequent subluxation. Patients report pain, catching, and instability of the affected finger. Subluxation of the extensor tendon normally occurs to the ulnar side.

Exam shows abnormal extensor tendon subluxation with flexion/extension normally to the ulnar side. X-rays are often normal. Ultrasound confirms diagnosis.

Partial tears can be treated with splinting and hand therapy. Complete tears and chronic injuries (>3 months) require surgical repair or reconstruction to prevent tendon dislocation.

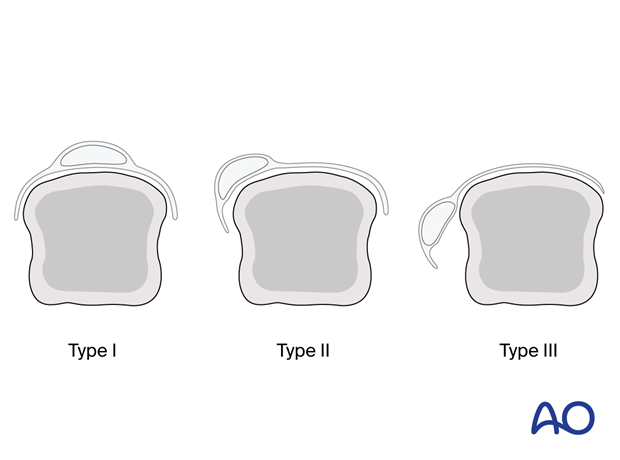

Sagittal band injuries may be assessed as follows (according to the classification of Rayan and Murray).

- Type I: without extensor tendon instability

- Type II: with tendon subluxation

- Type III: with tendon dislocation

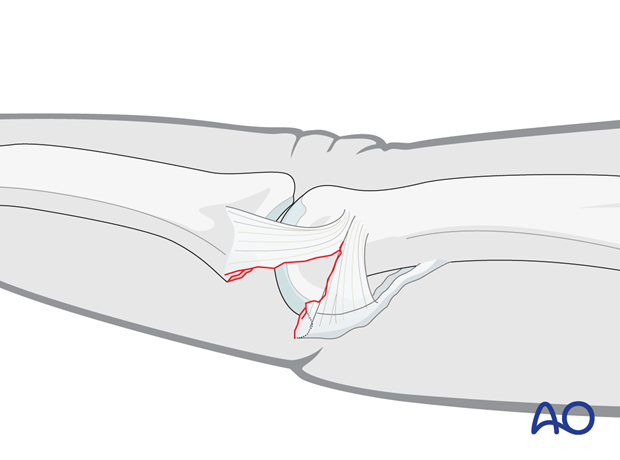

Volar plate injuries

Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint hyperextension injuries can cause partial or complete avulsions of the volar plate, potentially leading to instability and hyperextension of the affected interphalangeal joint.

Diagnosis is made by physical exam revealing joint laxity and can be confirmed by ultrasound. Lateral x-rays can show osseous avulsion.

Tears without lateral instability can normally be treated with buddy strapping and early mobilization. If patients show hyperextension in the PIP joint, an extension block splint may be applied for the first 2–3 weeks. Open repair or reconstruction is normally not necessary.

8. References

- Allison DM. Anatomy of the collateral ligaments of the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 2005 Sep;30(5):1026–1031.

- Balakrishnan TM, Subbaraj H, Jaganmohan J. Anatomy of Landsmeer Ligaments-Redefined. Indian J Plast Surg. 2019 May;52(2):195–200.

- Berdia S, Short WH, Werner FW, et al. The hysteresis effect in carpal kinematics. J Hand Surg Am. 2006 Apr;31(4):594–600.

- Caravaggi P, Shamian B, Uko L, et al. In vitro kinematics of the proximal interphalangeal joint in the finger after progressive disruption of the main supporting structures. Hand (N Y). 2015 Sep;10(3):425–432.

- Clavero JA, Alomar X, Monill JM, et al. MR imaging of ligament and tendon injuries of the fingers. Radiographics. 2002 Mar–Apr;22(2):237–256.

- Gupta P, Lenchik L, Wuertzer SD, et al. High-resolution 3-T MRI of the fingers: review of anatomy and common tendon and ligament injuries. Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Mar;204(3):W314-W323.

- Lee SW, Ng ZY, Fogg QA. Three-dimensional analysis of the palmar plate and collateral ligaments at the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014 May;39(4):391–397.

- Minamikawa Y, Horii E, Amadio PC, et al. Stability and constraint of the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1993 Mar;18(2):198–204.

- Pang EQ, Yao J. Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Finger Proximal Interphalangeal Joint. Hand Clin. 2018 May;34(2):121–126.

- Rayan GM, Murray D. Classification and treatment of closed sagittal band injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 1994 Jul;19(4):590–594.