Compartment syndrome in the thigh

1. Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a true surgical emergency.

It is caused by increasing tissue pressure which prevents capillary blood flow, leading to ischemia in muscle and nerve tissue.

If not treated, tissue necrosis with permanent loss of function may occur.

Compartment syndrome may occur as a result of:

- high-energy limb injuries

- crushing injuries

- reperfusion injury

- burns

Compartment syndrome occurs in:

- fascial compartments below the elbow

- fascial compartments below the knee

- rarely, above the elbow and knee

Treatment of compartment syndrome requires surgical release of the closed osteo-fascial compartments.

2. Definition

Compartment syndrome is characterized by a rise in pressure within a closed fascial compartment, sufficient to prevent effective capillary perfusion in muscle and nerve tissue.

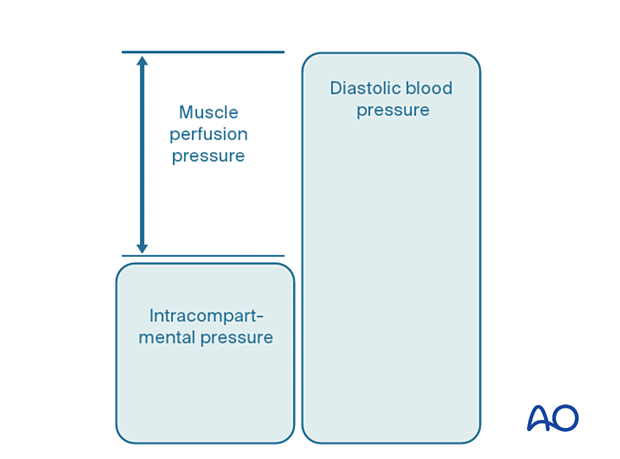

Normal tissue pressure is 0–10 mm Hg. The capillary filling pressure is essentially diastolic arterial pressure. When tissue pressure approaches the diastolic pressure, capillary blood flow ceases.

3. Diagnosis

Symptoms

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and appreciation of progressively severe symptoms which include the following:

- unexpected pain with increasing analgesia requirement

- paresthesia

- progressive loss of sensation

- progressive loss of power

The diagnosis is difficult in patients with:

- head injury

- loss of consciousness for other reasons

- high spinal injury

- regional nerve blockade

Signs

The signs of an evolving compartment syndrome include:

- tenderness and swelling of the affected compartment

- increase in pain with passive muscle stretching

- compartmental muscle weakness

- later, sensory disturbance in the distribution of nerves traversing the compartment

- later, weakness of muscles innervated by nerves traversing the compartment

4. Principles

General treatment principles

Effective management of an impending or established compartment syndrome requires:

- recognition of the risk of, or actual compartment syndrome (symptoms and signs)

- understanding the pathophysiology

- intracompartmental pressure measurement

- recognition of the importance of early surgical treatment

- resources to manage the aftercare and rehabilitation requirements

Pathophysiology

The most reliable measure of critical intracompartmental perfusion is the muscle perfusion pressure (MPP).

MPP is equal to the difference between diastolic blood pressure (dBP) and measured intramuscular pressure.

This difference in pressure reflects tissue perfusion more reliably than absolute intramuscular pressure.

When the muscle perfusion pressure is reduced to a level at which no capillary perfusion occurs, hypoxia leading to ischemia, and subsequent necrosis will occur.

The critical muscle perfusion pressure depends on the specific anatomical compartment affected.

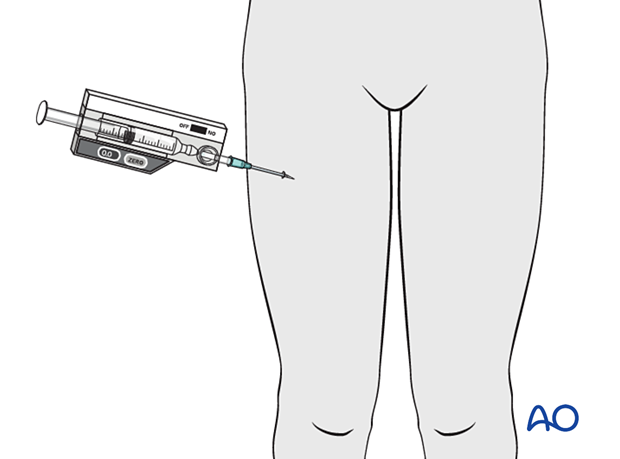

Intracompartmental pressure measurement

When the clinical symptoms and signs of compartment syndrome are present, there is no benefit in measuring intracompartmental pressures, and an immediate fasciotomy should be performed.

When it is difficult to confirm the diagnosis, intracompartmental pressure measurement is helpful:

- to confirm the diagnosis

- to monitor a compartment at risk of increasing pressures

- to avoid unnecessary fasciotomy

- to measure intracompartmental pressures after decompression if symptoms persist

Compartment pressures should be measured at the area of maximal swelling or trauma. There are several techniques for the measurement of intracompartmental tissue pressure:

- commercially available intracompartmental pressure device

- large-bore needle and manometer

- electronic strain gauge

If the necessary equipment is not available for direct intracompartmental pressure measurement, then the diagnosis must be assumed if there is reasonable clinical suspicion, and fasciotomies must be performed.

Timing

Reversible ischemiaIn established muscle compartment syndrome, nerve and muscle tissue will become ischemic within less than two hours.

It is therefore of paramount importance that the intracompartmental pressure be released as an emergency intervention.

It is generally accepted that after 6–8 hours of inadequate muscle perfusion pressure (MPP), extensive muscle necrosis is inevitable. Release of the muscle compartments involved will not prevent severe muscle contracture.

Fasciotomy of compartments within which muscle necrosis has already happened has a high risk of infection.

Amputation may be required.

5. Compartmental anatomy

Introduction

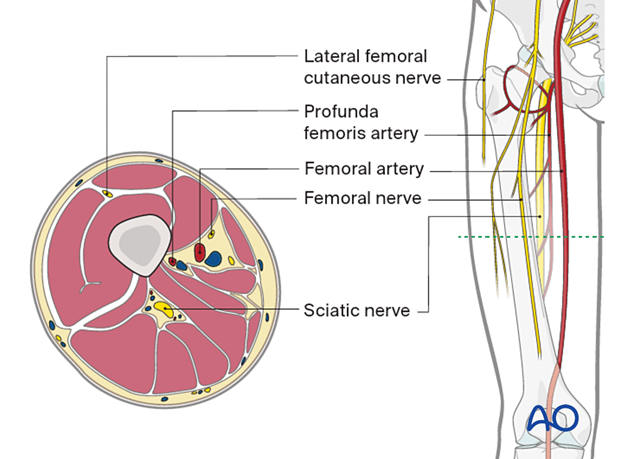

The diaphysis of the femur is surrounded by a thick muscular envelope. The major neurovascular structures are located medially and posteriorly.

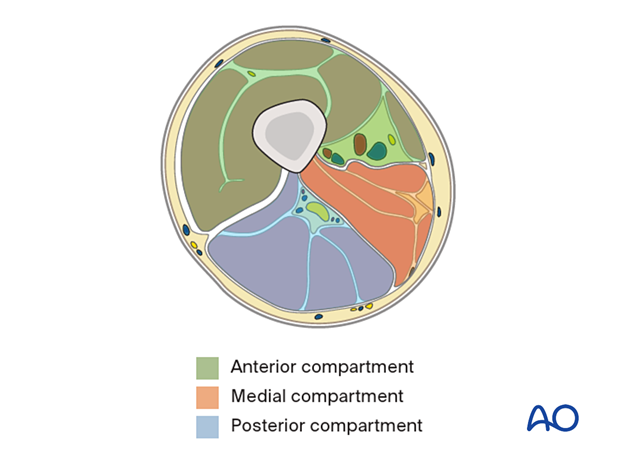

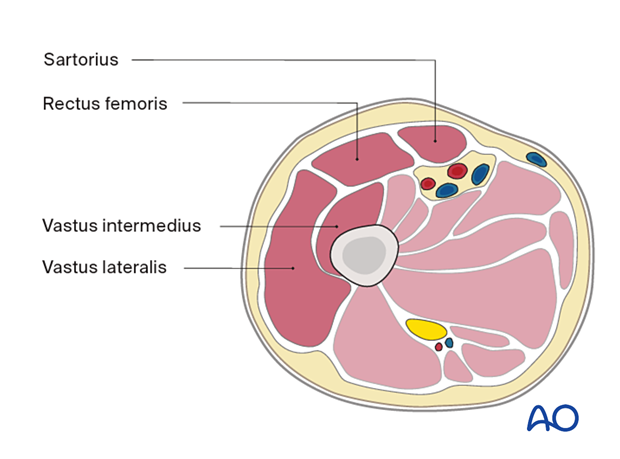

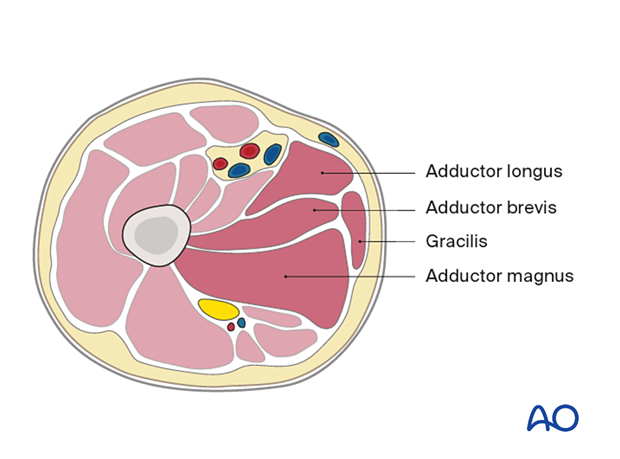

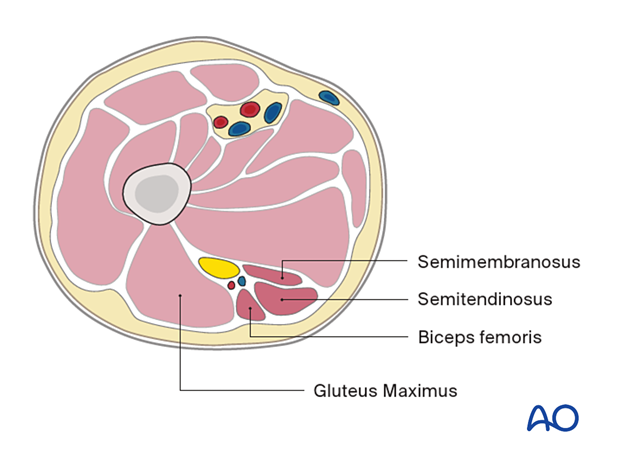

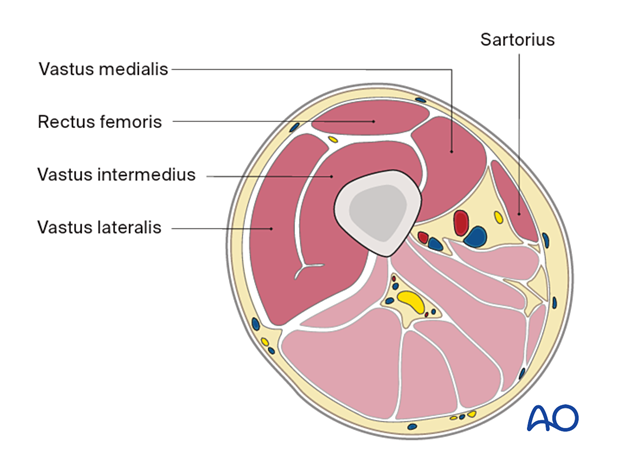

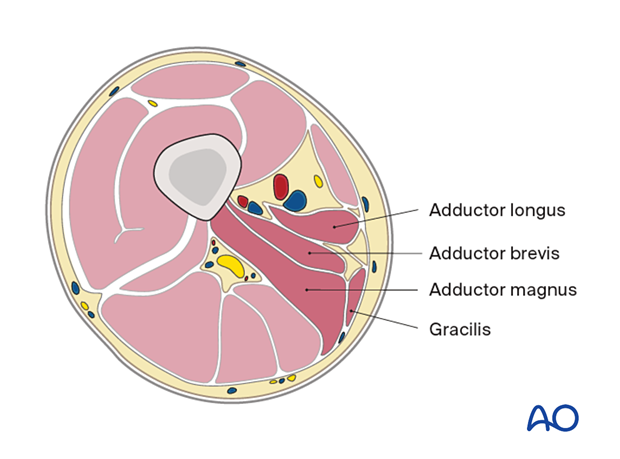

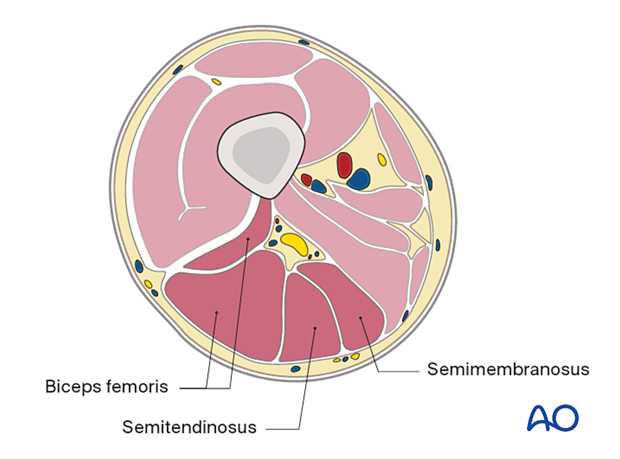

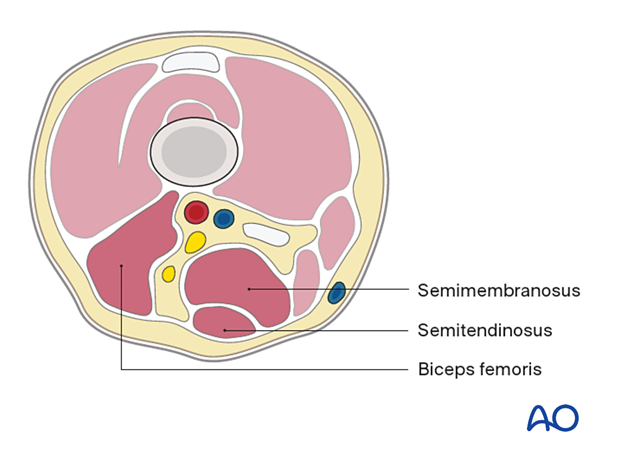

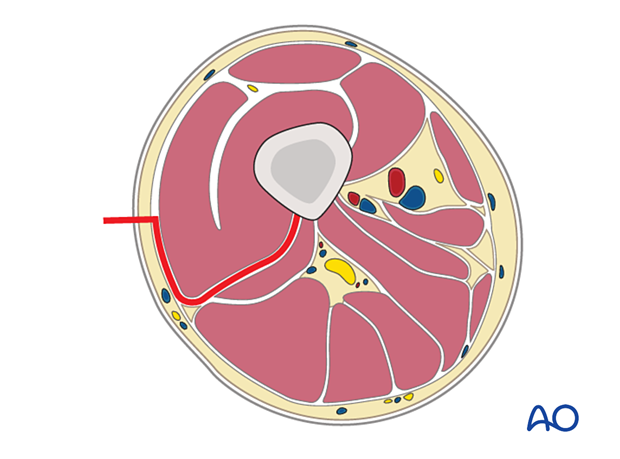

The compartments of the thigh are shown here.

The illustration shows a cross section of the thigh at the level of the mid femur.

Proximal femur

Anterior compartment:- Sartorius

- Rectus femoris

- Vastus intermedius

- Vastus lateralis

- Adductor longus

- Adductor brevis

- Gracilis

- Adductor magnus

- Semimembranosus

- Semitendinosus

- Biceps femoris

Mid femur

Anterior compartment- Sartorius

- Vastus medialis

- Rectus femoris

- Vastus intermedius

- Vastus lateralis

- Adductor longus

- Adductor brevis

- Adductor magnus

- Gracilis

- Biceps femoris

- Semitendinosus

- Semimembranosus

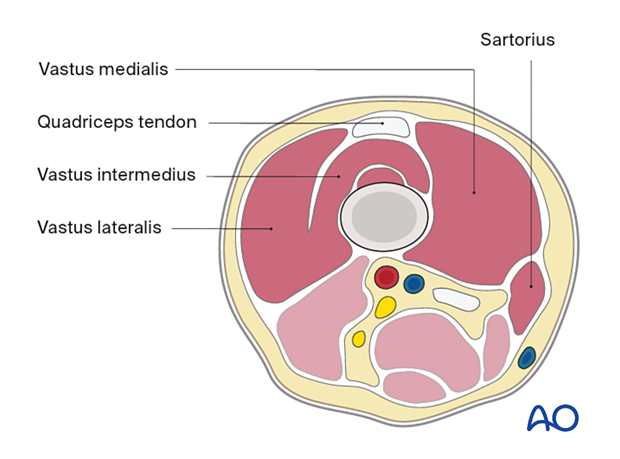

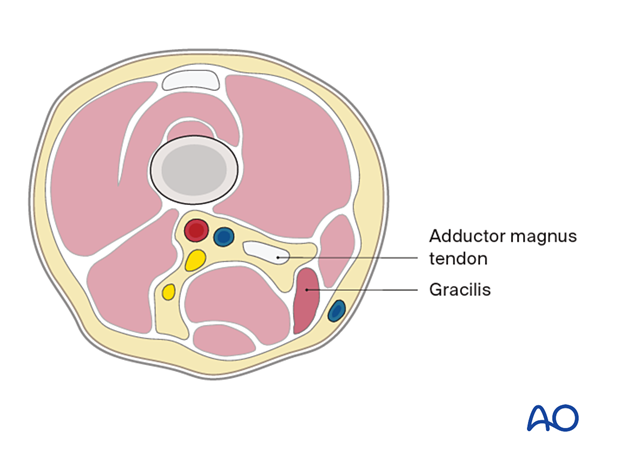

Distal femur

Anterior compartment- Sartorius

- Vastus medialis

- Quadriceps tendon

- Vastus intermedius

- Vastus lateralis

- Adductor magnus tendon

- Gracilis

- Semimembranosus

- Semitendinosus

- Biceps femoris

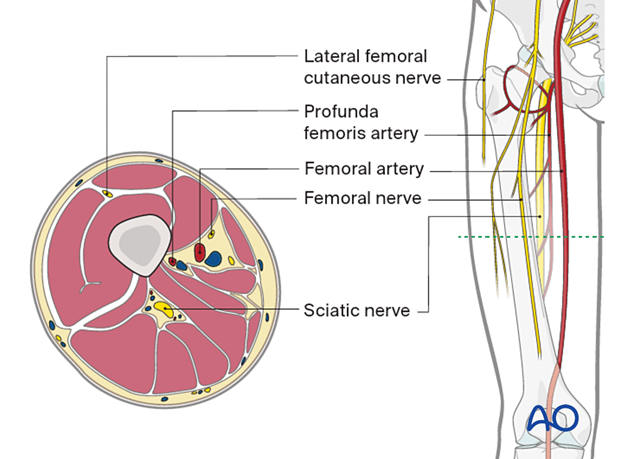

Neurovascular anatomy

The neurovascular anatomy of the femur includes the following:

- Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

- Profunda femoris artery

- Femoral artery

- Femoral nerve

- Sciatic nerve

6. Fasciotomies

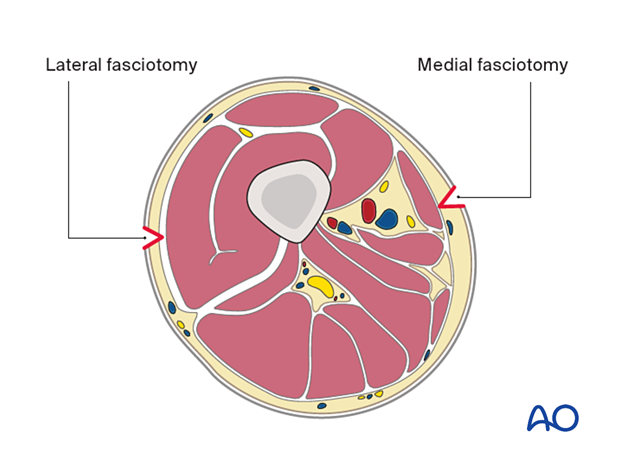

Two fasciotomies must be performed to adequately decompress the thigh: lateral and medial.

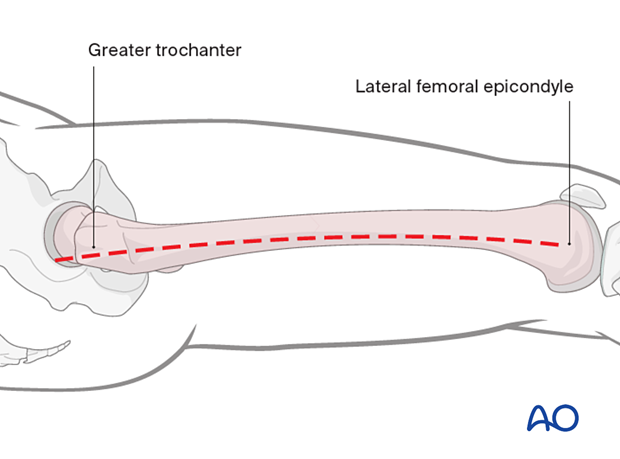

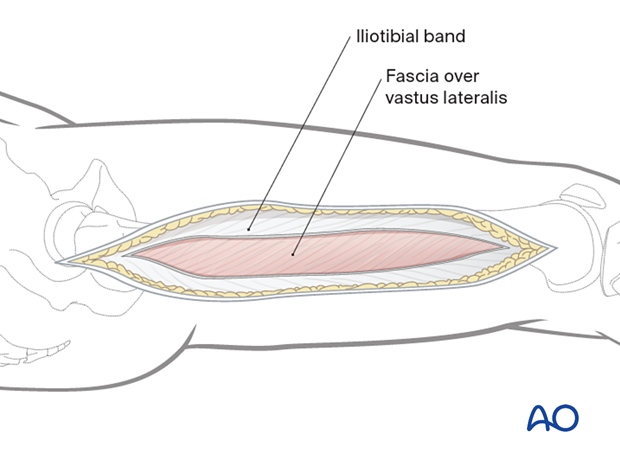

Lateral fasciotomy skin incision

An incision is made along an imaginary line between the lateral femoral epicondyle and the greater trochanter, along the length of the femur.

The fascia lata/iliotibial band is incised with a scalpel and split with scissors parallel to the skin incision, along its fibers.

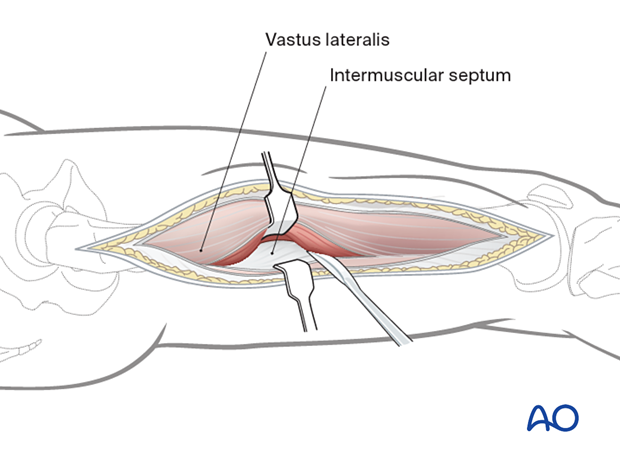

The muscle fascia over the vastus lateralis is exposed.

As vastus lateralis is elevated from the intermuscular septum, the perforating vessels are ligated to avoid deep compartment bleeding. The major vessels and nerves are located medially/posteromedially to the femoral shaft and are not exposed using this approach.

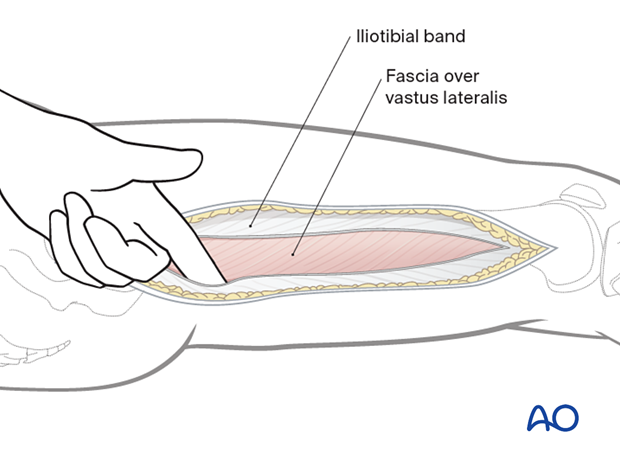

The Iliotibial band is then separated by blunt dissection from the vastus lateralis.

The vastus lateralis is retracted anteromedially.

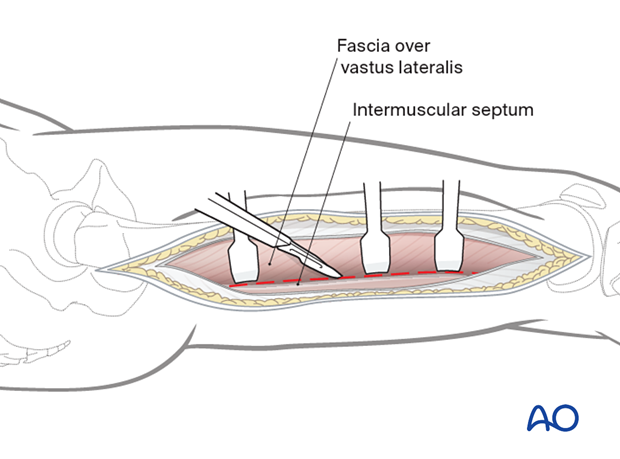

The muscle fascia investing the vastus lateralis is incised about 1 cm anterior to the intermuscular septum.

The muscle is detached from the lateral intermuscular septum and the linea aspera with a periosteal elevator.

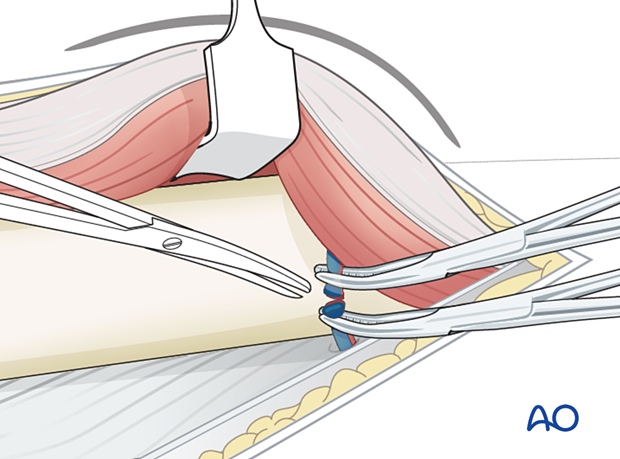

The perforating vessel bundles must be identified.

These vessels perforate the lateral intermuscular septum from the posterior side and run anteriorly, remaining close to the femoral shaft.

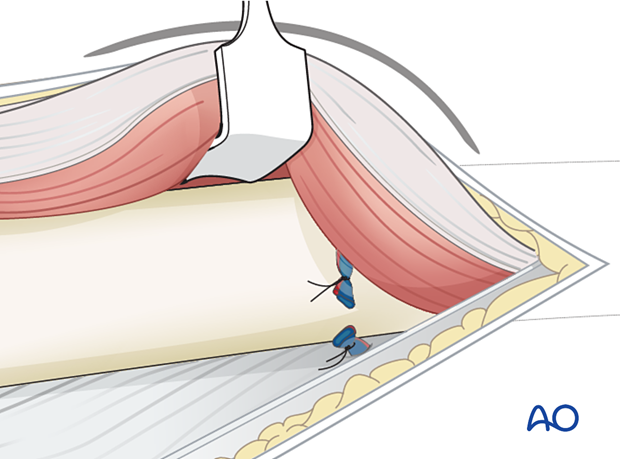

Larger vessel bundles may be ligated, smaller ones can be cauterized with diathermy.

The intramuscular septum is now split longitudinally for the full length of the incision to release the posterior compartment.

Medial fasciotomy

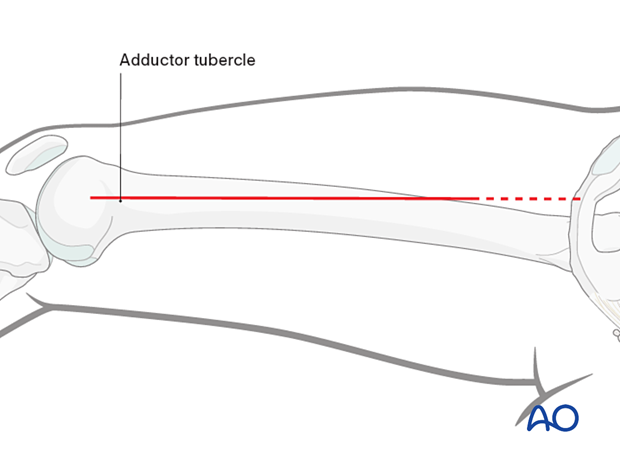

Skin incisionA skin incision is made in the line of the tendon of the adductor magnus. The adductor tubercle is identified, and the line of the adductor tendon is marked proximally. A straight-line incision is made along the adductor magnus. The incision can be extended as far proximally as needed.

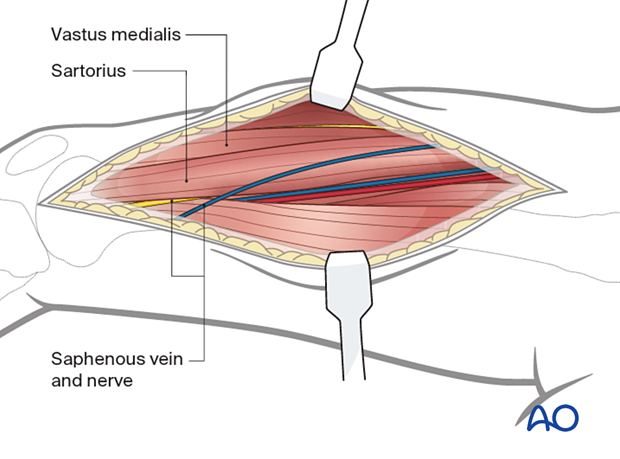

At the distal end of the incision, identify the vastus medialis and sartorius. Identify and protect the saphenous vein and nerve.

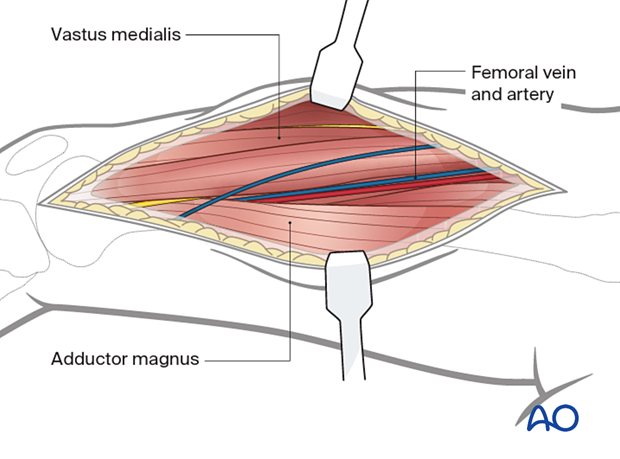

At the middle part of the incision identify the vastus medialis and adductor magnus. Identify and protect the femoral vein and femoral artery posterior to the vastus medialis.

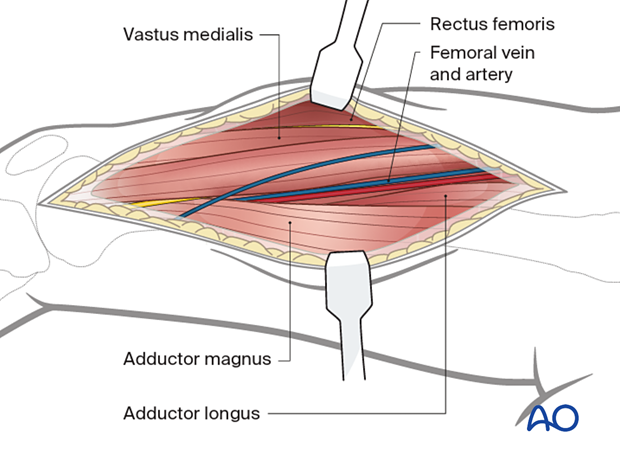

At the proximal end of the incision identify the vastus medialis, rectus femoris, and adductor longus and adductor magnus. Identify and protect the femoral artery and vein.

After identifying the muscular and neuromuscular structures of the medial thigh, perform complete, longitudinal fasciotomies of all muscle groups.

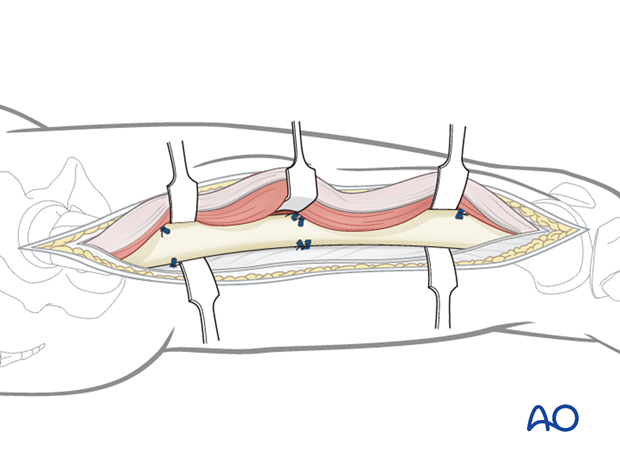

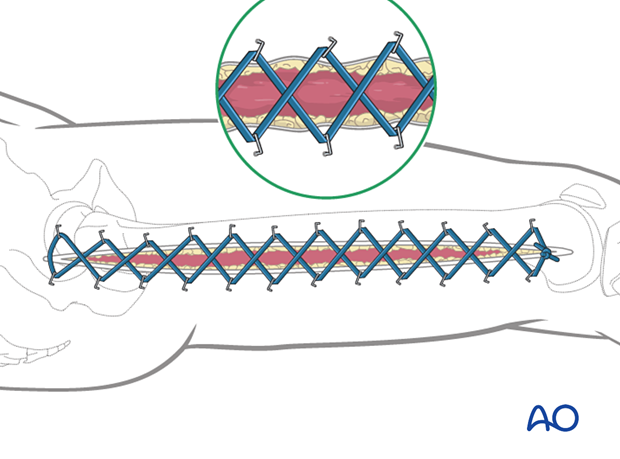

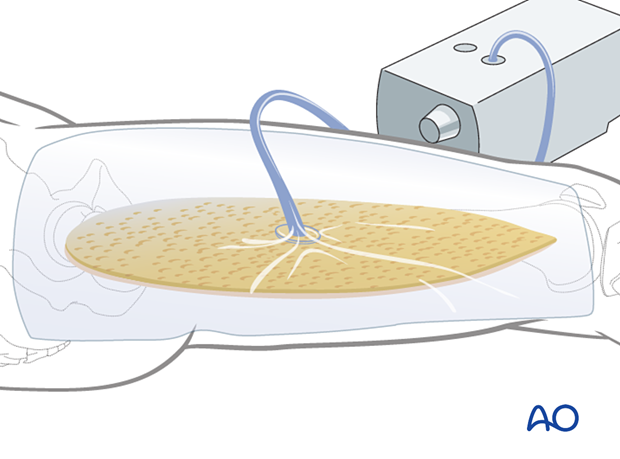

Temporary soft-tissue management

After a fasciotomy or fasciotomies have been performed, skin edges retract and can become difficult to close. Careful use of elastic retention sutures (elastic vessel loops woven through skin staples) can help counteract excessive skin contraction while still allowing the decompressed muscles to swell without any undue tension over them. Temporary coverage of the wounds can be obtained with either a wound vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device or coverage with saline-soaked gauze bandages. These dressings or the wound VAC can be kept on until the patient returns for an attempt at secondary closure.

Delayed soft-tissue management: primary closure

If the swelling of the limb adequately decreases upon subsequent return to the operating room, primary closure of the fasciotomy wounds can occur. It is important not to perform primary closure if there is any concern about persistent swelling; secondary coverage options exist. In many instances, application of an incisional wound vac can enhance wound healing.

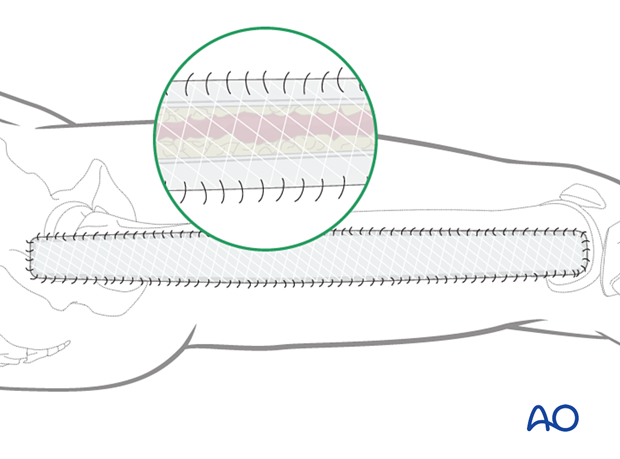

Delayed soft-tissue management: secondary coverage

If persistent swelling exists but wound closure is necessary, particularly for fractures that have been fixed, secondary wound coverage options are necessary. These include split thickness skin grafting, muscle flaps, or musculocutaneous flaps. In many instances wound vacs are employed to enhance wound healing.

It is imperative to cover fractures that have been fixed in a timely manner so as to minimize the risk of subsequent infection. In the case of open tibia fractures with soft-tissue loss, the literature strongly recommends definitive fracture fixation and soft-tissue coverage within seven days from the time of injury.

7. Aftercare

Splintage

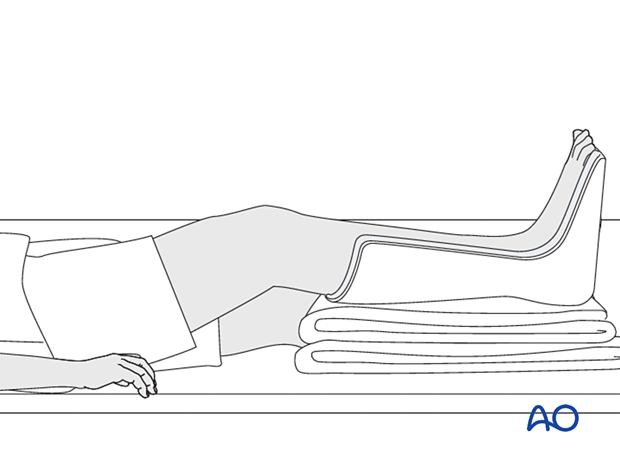

It is important to splint the knee in a semi-flexed position, and the foot and ankle in a neutral position to maintain a plantigrade foot.

Rehabilitation

Once wound healing has occurred, it is recommended to initiate range of motion exercises to minimize the development of contracture. Strengthening can begin at the discretion of the treating surgeon depending on the soft-tissue and bone injuries sustained.

Limitation of flexion of the knee due to contractures in the anterior (extensor or quadriceps) compartment is avoided by early implementation of range of motion exercises supervised by a physical therapist.

8. References

General compartment syndrome references

Gourgiotis S, Villias C, Germanos S, et al Acute limb compartment syndrome: a review. J Surg Educ. 2007 64(3):178-86.

Mabee JR Compartment syndrome: a complication of acute extremity trauma. J Emerg Med.1994 12(5):651-6.

McQueen MM, Duckworth AD. The diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome: a review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2014 Oct;40(5):521-8.

McQueen MM, Gaston P, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome. Who is at risk? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000 Mar;82(2):200-3.

Powell-Bowns MF, Littlechild JE, Yapp LZ, et al. Tibial shaft fractures - to monitor or not? a multi-centre 2 year comparative study assessing the diagnosis of compartment syndrome in patients with tibial diaphyseal fractures. Injury. 2021 Oct;52(10):3111-3116.

von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet. 2015 Sep 26;386(10000):1299-1310.

Compartment syndrome in the thigh

Kanlic EM, Pinski SE, Verwiebe EG, et al. Acute morbidity and complications of thigh compartment syndrome: A report of 26 cases. Patient Saf Surg. 2010 Aug 19;4(1):13.

Masini BD, Racusin AW, Wenke JC, et al. Acute compartment syndrome of the thigh in combat casualties. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2013 Spring;22(1):42-9.

Mithoefer K, Lhowe DW, Vrahas MS, et al. Functional outcome after acute compartment syndrome of the thigh. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006 Apr;88(4):729-37.

Rodriguez J, Suneja N, von Keudell A, et al. Surgical demographics of acute thigh compartment syndrome. Injury. 2022 Oct;53(10):3481-3485.