Compartment syndrome in the leg

1. Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a true surgical emergency.

It is caused by increasing tissue pressure which prevents capillary blood flow, leading to ischemia in muscle and nerve tissue.

If not treated, tissue necrosis with permanent loss of function may occur.

Compartment syndrome may occur as a result of:

- high-energy limb injuries

- crushing injuries

- reperfusion injury

- burns

Compartment syndrome occurs in:

- fascial compartments below the elbow

- fascial compartments below the knee

- rarely, above the elbow and knee

Treatment of compartment syndrome requires surgical release of the closed osteo-fascial compartments.

2. Definition

Compartment syndrome is characterized by a rise in pressure within a closed fascial compartment, sufficient to prevent effective capillary perfusion in muscle and nerve tissue.

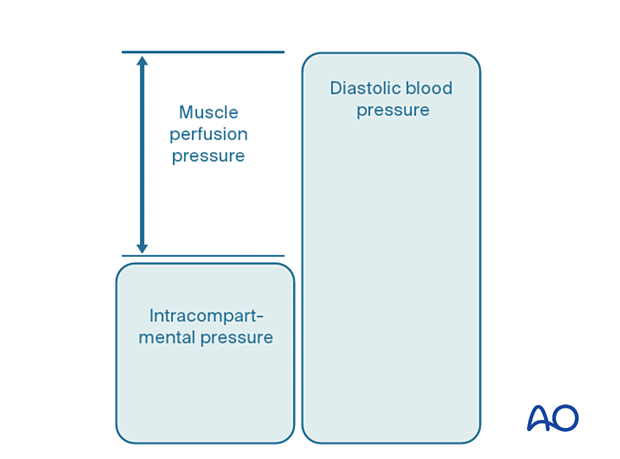

Normal tissue pressure is 0–10 mm Hg. The capillary filling pressure is essentially diastolic arterial pressure. When tissue pressure approaches the diastolic pressure, capillary blood flow ceases.

3. Diagnosis

Symptoms

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and appreciation of progressively severe symptoms which include the following:

- unexpected pain with increasing analgesia requirement

- paresthesia

- progressive loss of sensation

- progressive loss of power

The diagnosis is difficult in patients with:

- head injury

- loss of consciousness for other reasons

- high spinal injury

- regional nerve blockade

Signs

The signs of an evolving compartment syndrome include:

- tenderness and swelling of the affected compartment

- increase in pain with passive muscle stretching

- compartmental muscle weakness

- later, sensory disturbance in the distribution of nerves traversing the compartment

- later, weakness of muscles innervated by nerves traversing the compartment

4. Principles

General treatment principles

Effective management of an impending or established compartment syndrome requires:

- recognition of the risk of, or actual compartment syndrome (symptoms and signs)

- understanding the pathophysiology

- intracompartmental pressure measurement

- recognition of the importance of early surgical treatment

- resources to manage the aftercare and rehabilitation requirements

Pathophysiology

The most reliable measure of critical intracompartmental perfusion is the muscle perfusion pressure (MPP).

MPP is equal to the difference between diastolic blood pressure (dBP) and measured intramuscular pressure.

This difference in pressure reflects tissue perfusion more reliably than absolute intramuscular pressure.

When the muscle perfusion pressure is reduced to a level at which no capillary perfusion occurs, hypoxia leading to ischemia, and subsequent necrosis will occur.

The critical muscle perfusion pressure depends on the specific anatomical compartment affected.

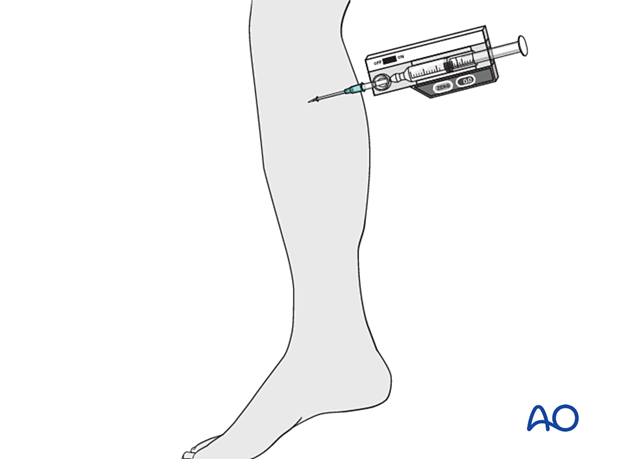

Intracompartmental pressure measurement

When the clinical symptoms and signs of compartment syndrome are present, there is no benefit in measuring intracompartmental pressures, and an immediate fasciotomy should be performed.

When it is difficult to confirm the diagnosis, intracompartmental pressure measurement is helpful:

- to confirm the diagnosis

- to monitor a compartment at risk of increasing pressures

- to avoid unnecessary fasciotomy

- to measure intracompartmental pressures after decompression if symptoms persist

Compartment pressures should be measured at the area of maximal swelling or trauma. There are several techniques for the measurement of intracompartmental tissue pressure:

- commercially available intracompartmental pressure device

- large-bore needle and manometer

- electronic strain gauge

If the necessary equipment is not available for direct intracompartmental pressure measurement, then the diagnosis must be assumed if there is reasonable clinical suspicion, and fasciotomies must be performed.

Timing

Reversible ischemiaIn established muscle compartment syndrome, nerve and muscle tissue will become ischemic within less than two hours.

It is therefore of paramount importance that the intracompartmental pressure be released as an emergency intervention.

It is generally accepted that after 6–8 hours of inadequate muscle perfusion pressure (MPP), extensive muscle necrosis is inevitable. Release of the muscle compartments involved will not prevent severe muscle contracture.

Fasciotomy of compartments within which muscle necrosis has already happened has a high risk of infection.

Amputation may be required.

5. Compartmental anatomy

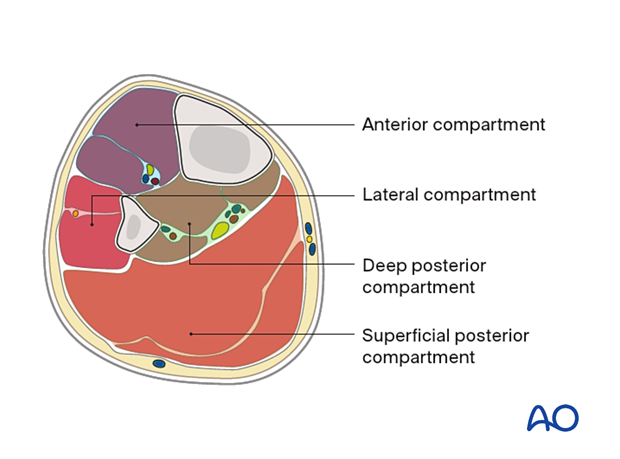

There are four main compartments in the leg:

- Anterior compartment

- Lateral compartment

- Deep posterior compartment

- Superficial posterior compartment

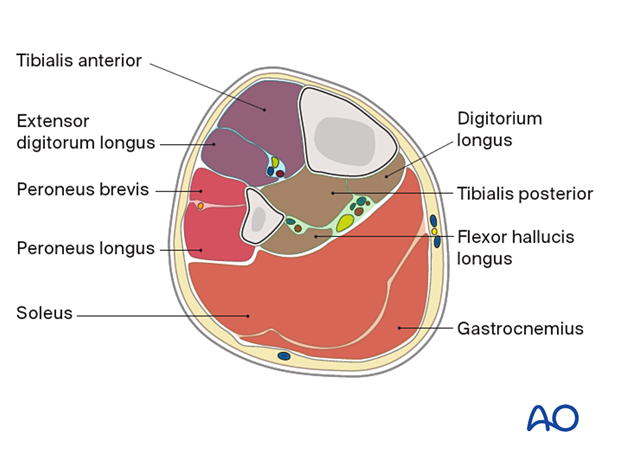

Muscular anatomy

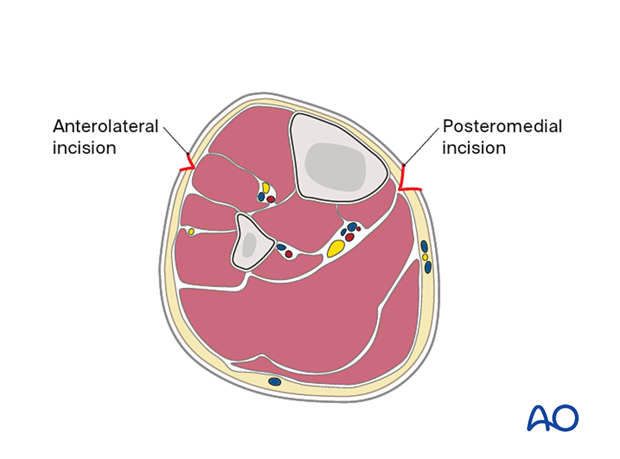

A comprehension of the anatomy of the four compartments is required for safe decompression. The anterior and lateral muscle compartments are approached via an anterolateral incision: the superficial and deep posterior compartments are approached through a separate medial incision.

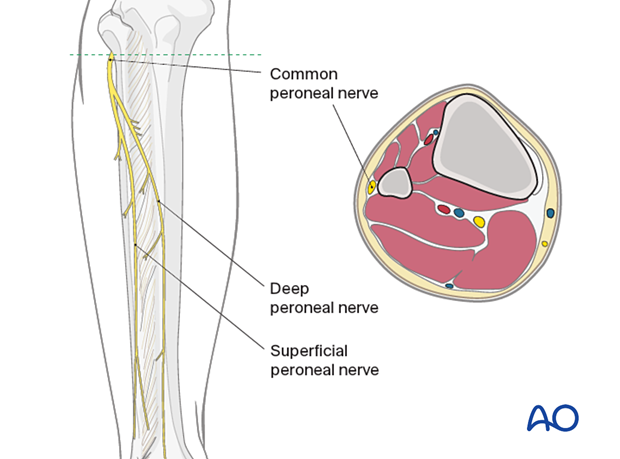

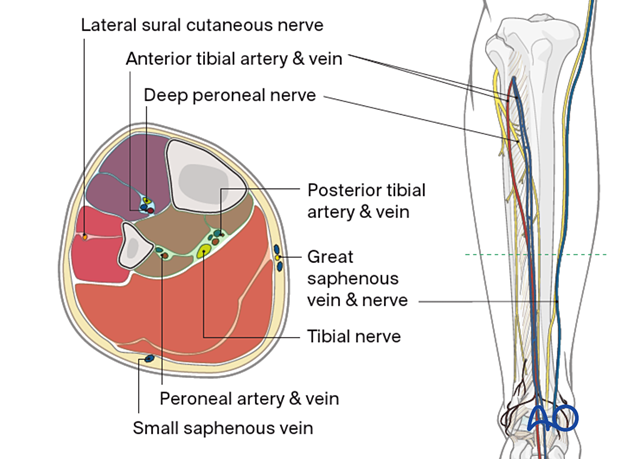

Neurovascular anatomy

It is important to protect subcutaneous nerves, particularly the common peroneal nerve where it crosses the fibula proximally as well as the superficial peroneal nerve in the distal end of the tibia.

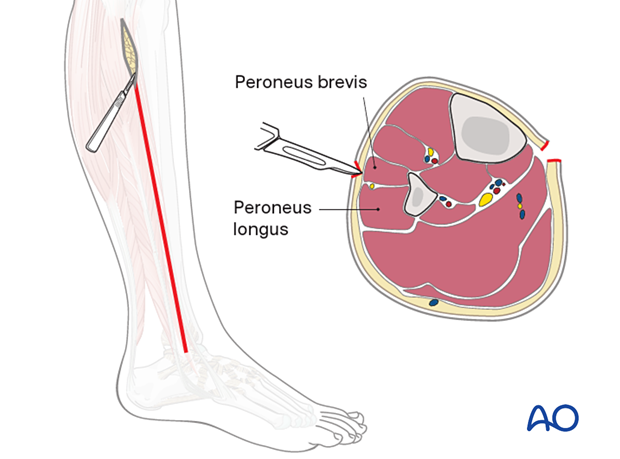

The main superficial neurovascular structures at risk in these approaches are, medially, the great saphenous vein and its accompanying nerve, and laterally, the superficial peroneal nerve. The superficial peroneal nerve branches from the common peroneal nerve near the neck of the fibula and passes between the peroneus longus and brevis muscles, supplying motor branches to these muscles. The superficial branch then continues onto the dorsum of the foot to supply sensory fibers to the skin there.

The main deep neurovascular bundle at risk is the posterior tibial, as it lies on the posterior aspect of the tibialis posterior and flexor digitorum longus muscles, and medial to the belly of the flexor hallucis longus. Remember that this is more superficial at the medial ankle.

6. Fasciotomies

In the lower leg, one, or more of the four osteofascial muscle compartments may be involved. Typically, with an acute compartment syndrome, it is safest to release all four compartments.

Either of the following techniques should be used:

- A dual-incision technique (illustrated here)

- A parafibular single-incision fasciotomy

These techniques are described below.

Fibulectomy/fasciotomy, described in the vascular surgical literature, is contraindicated for trauma patients.

Dual-incision, four-compartment fasciotomy

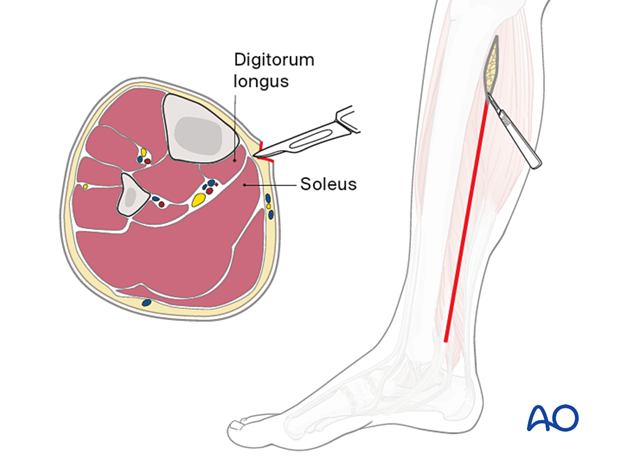

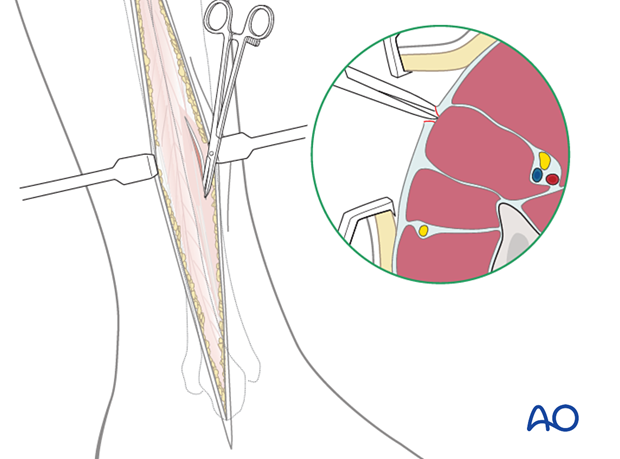

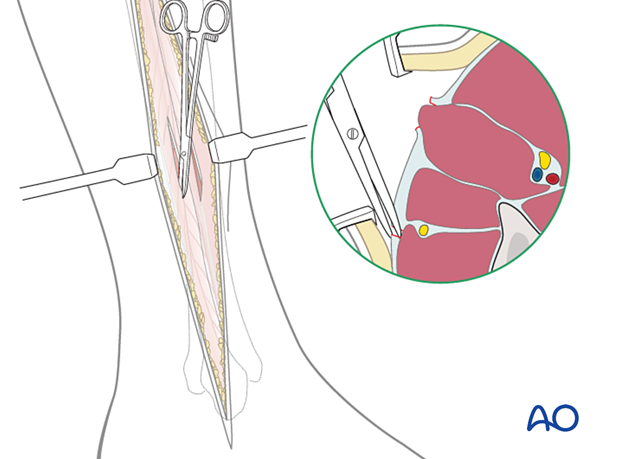

Posteromedial incisionThe two posterior compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision in the lower leg, two centimeters behind the palpable posteromedial edge of the tibia.

After reaching the fascia, undermine anteriorly to the posterior tibial margin, in order to avoid the saphenous vein and nerve. The deep posterior compartment here is superficial and readily accessible.

The fascia of the deep posterior compartment is carefully opened distally and proximally, under the belly of the soleus muscle, paying special attention to the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle.

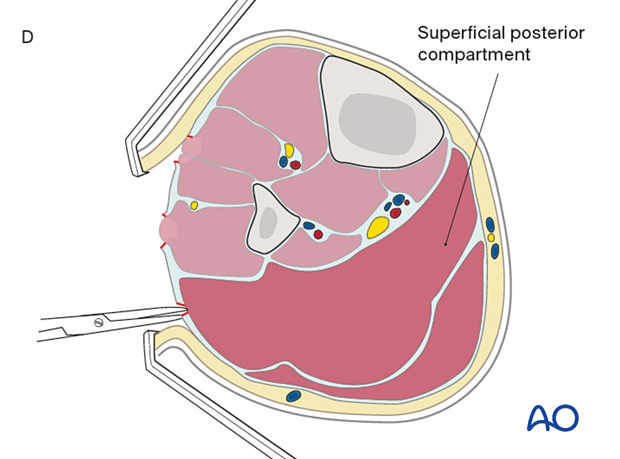

Through the same incision, the fascia of the superficial posterior compartment is opened longitudinally, two centimeters posterior and parallel to the posterior border of the tibia.

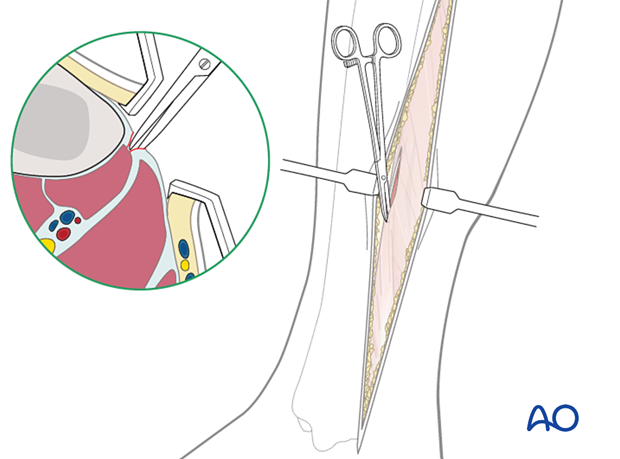

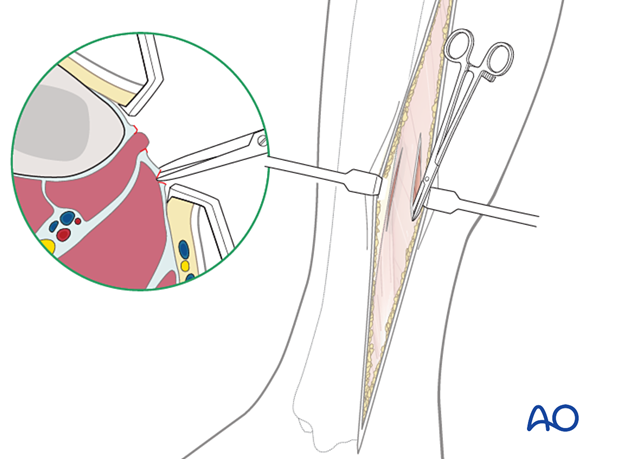

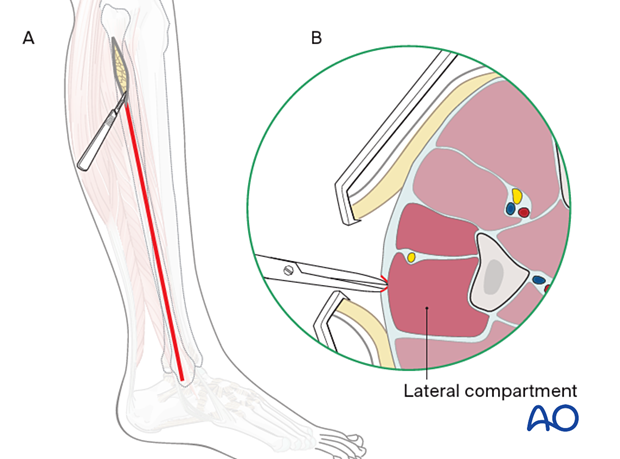

The anterior and lateral compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision on the lateral aspect of the leg, two centimeters anterior to the fibular shaft and long enough to expose the whole length of the compartments. The incision lies approximately over the anterior intermuscular septum that divides the anterior and lateral compartments and allows easy access to both.

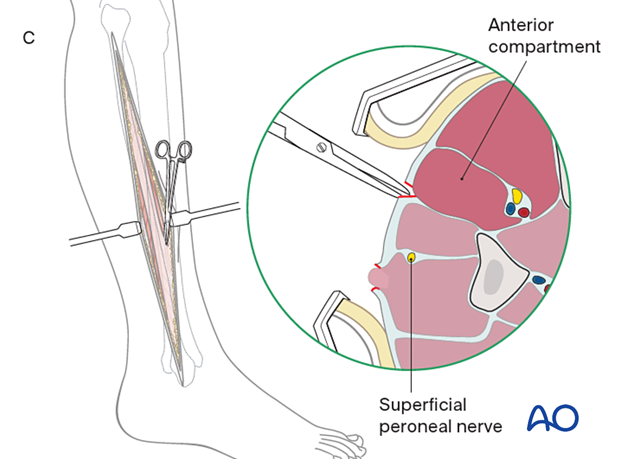

A full-length incision is made in the fascia of the anterior compartment, midway between the septum and the tibial crest. The fascia is opened proximally and distally, protecting the cutaneous nerves.

The lateral compartment fasciotomy is in line with the fibular shaft. Directing the scissors towards the lateral malleolus helps avoid the superficial peroneal nerve as it exits from the fascia in the distal third of the leg near the septum and courses anteriorly.

Single-incision, parafibular four-compartment fasciotomy

This technique avoids a medial incision and releases the posterior compartments, as well as the anterior and lateral compartments, through a single lateral incision. It is essential to ensure that the deep posterior compartment fascia is adequately released. If necessary, intracompartmental pressure monitoring should be used to confirm decompression.

A) An incision is made from the fibular neck to the lateral malleolus.

B) The lateral compartment is opened.

C) Retracting the anterior skin exposes the fascia of the anterior compartment, which is opened, with care being taken to avoid the superficial peroneal nerve.

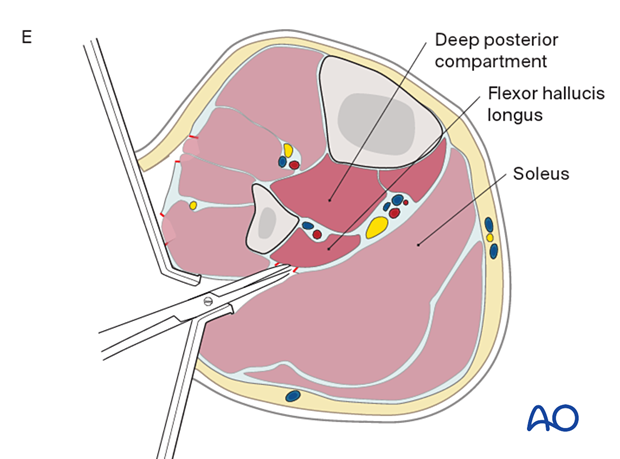

D) The posterior skin is retracted to expose the fascia of the superficial posterior compartment, which is opened.

E) The lateral compartment is retracted anteriorly. The soleus is released from the fibular shaft and is retracted posteriorly, exposing the fascia of the deep posterior compartment, which is opened.

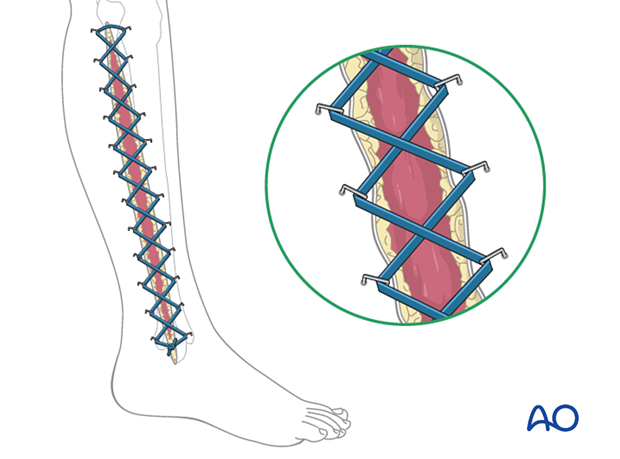

Temporary soft-tissue management

Delayed soft-tissue management: primary closure

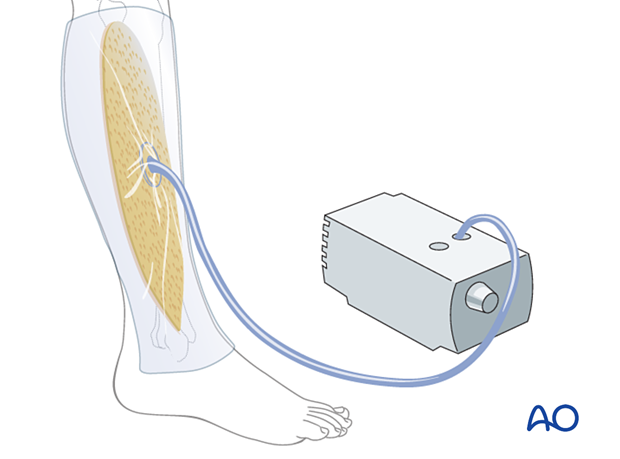

If the swelling of the limb adequately decreases upon subsequent return to the operating room, primary closure of the fasciotomy wounds can occur. It is important not to perform primary closure if there is any concern about persistent swelling; secondary coverage options exist. In many instances, application of an incisional wound vac can enhance wound healing.

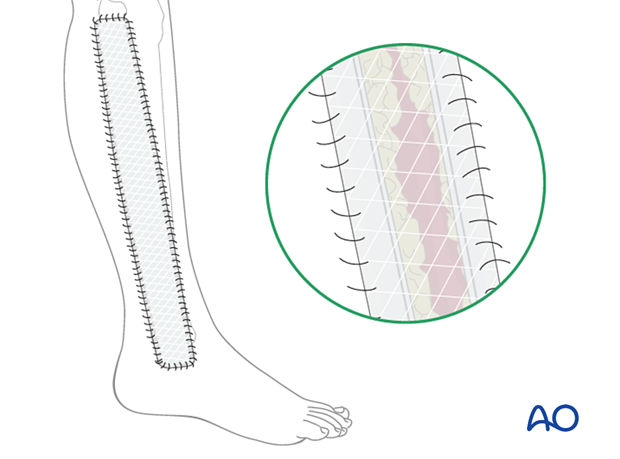

Delayed soft-tissue management: secondary coverage

If persistent swelling exists but wound closure is necessary, particularly for fractures that have been fixed, secondary wound coverage options are necessary. These include split thickness skin grafting, muscle flaps, or musculocutaneous flaps. In many instances wound vacs are employed to enhance wound healing.

It is imperative to cover fractures that have been fixed in a timely manner so as to minimize the risk of subsequent infection. In the case of open tibia fractures with soft-tissue loss, the literature strongly recommends definitive fracture fixation and soft-tissue coverage within seven days from the time of injury.

7. Aftercare

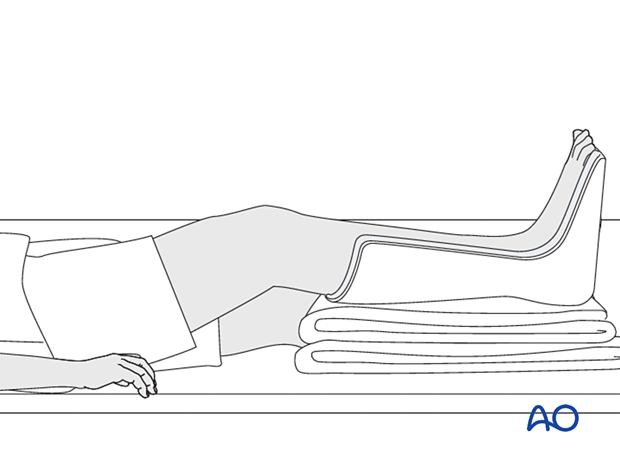

Splintage

It is important to splint the foot and ankle in a neutral position to maintain a plantigrade foot, particularly if any muscle damage has occurred, as contractures may develop. This can be done with a well-padded plaster back-slab, or with the extension of an external fixator to the foot. Maintain toe mobility with passive stretching.

Rehabilitation

Once wound healing has occurred, it is recommended to initiate range of motion exercises to minimize the development of contracture. Strengthening can begin at the discretion of the treating surgeon depending on the soft-tissue and bone injuries sustained.

Equinus contractures of the ankle are very common, and vigilance is necessary to prevent their development. The treating surgeon should follow patients at risk frequently to ensure that the patient is receiving appropriate physical therapy treatment.

8. References

General compartment syndrome references

Gourgiotis S, Villias C, Germanos S, et al Acute limb compartment syndrome: a review. J Surg Educ. 2007 64(3):178-86.

Mabee JR Compartment syndrome: a complication of acute extremity trauma. J Emerg Med.1994 12(5):651-6.

McQueen MM, Duckworth AD. The diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome: a review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2014 Oct;40(5):521-8.

McQueen MM, Gaston P, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome. Who is at risk? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000 Mar;82(2):200-3.

Powell-Bowns MF, Littlechild JE, Yapp LZ, et al. Tibial shaft fractures - to monitor or not? a multi-centre 2 year comparative study assessing the diagnosis of compartment syndrome in patients with tibial diaphyseal fractures. Injury. 2021 Oct;52(10):3111-3116.

von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet. 2015 Sep 26;386(10000):1299-1310.

Compartment syndrome in the leg

Du W, Hu X, Shen Y, et al. Surgical management of acute compartment syndrome and sequential complications. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019 Mar 4;20(1):98.

Konda SR, Kester BS, Fisher N, et al. Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Leg. J Orthop Trauma. 2017 Aug;31 Suppl 3:S17-S18.

Bodansky D, Doorgakant A, Alsousou J, et al. Acute Compartment Syndrome: Do guidelines for diagnosis and management make a difference? Injury. 2018 Sep;49(9):1699-1702.

Zhang D, Janssen SJ, Tarabochia M, et al. Risk factors for death and amputation in acute leg compartment syndrome. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020 Feb;30(2):359-365.

Shadgan B, Pereira G, Menon M, et al. Risk factors for acute compartment syndrome of the leg associated with tibial diaphyseal fractures in adults. J Orthop Traumatol. 2015 Sep;16(3):185-92.

Frink M, Klaus AK, Kuther G, et al. Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients. Injury. 2007 May;38(5):607-13.

Mubarak SJ, Owen CA. Double-incision fasciotomy of the leg for decompression in compartment syndromes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977 Mar;59(2):184-7.

Matsen FA 3rd, Winquist RA, Krugmire RB Jr. Diagnosis and management of compartmental syndromes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Mar;62(2):286-91.