Superior approach to the clavicle

1. Indication

The superior approach to the clavicle can be used for all lateral, medial, and diaphyseal clavicle fractures.

2. Anatomy

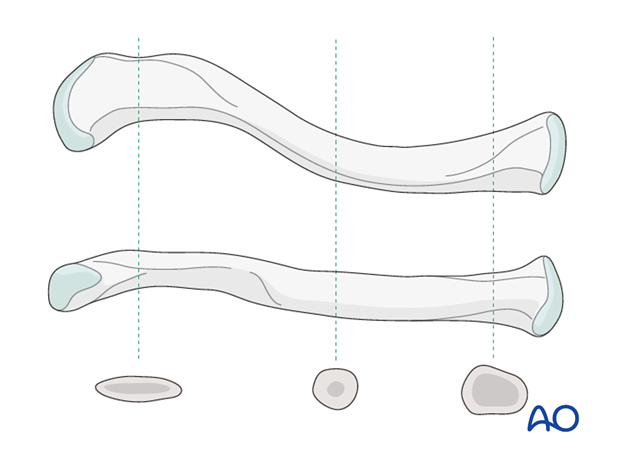

The clavicle is an S-shaped bone, anteriorly concave laterally and anteriorly convex medially. The cross sectional anatomy along its lateral to medial course changes from flat to tubular to prismatic. The junction from the flat region to the tubular region is a stress riser and this explains the higher incidence of midshaft fractures. Plates applied for lateral clavicular fractures are typically placed superiorly, while plates applied for diaphyseal of medial fractures can be placed anteriorly or superiorly.

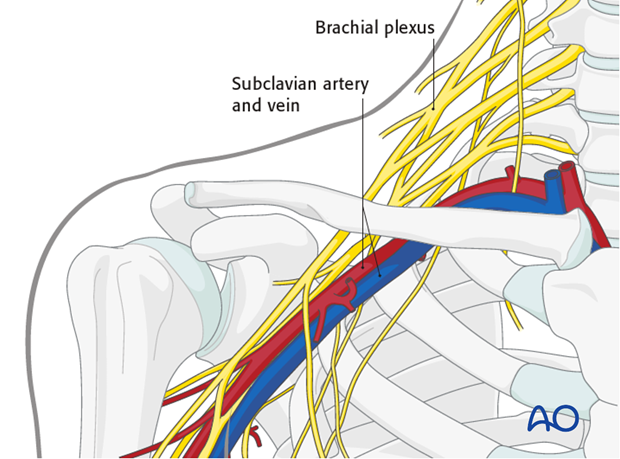

The neurovascular structures, namely, the subclavian artery and vein and the brachial plexus, pass from a posterosuperior to antero inferior direction, between the first rib and the clavicle at the junction of its medial and middle thirds and are thus vulnerable during surgery and instrumentation in this region. In the middle third or the tubular portion, the subclavius muscle and fascia protect the neurovascular structures from the fracture. However, to avoid injury to the neurovascular structures, care should be exercised when sharp instruments are used in this area.

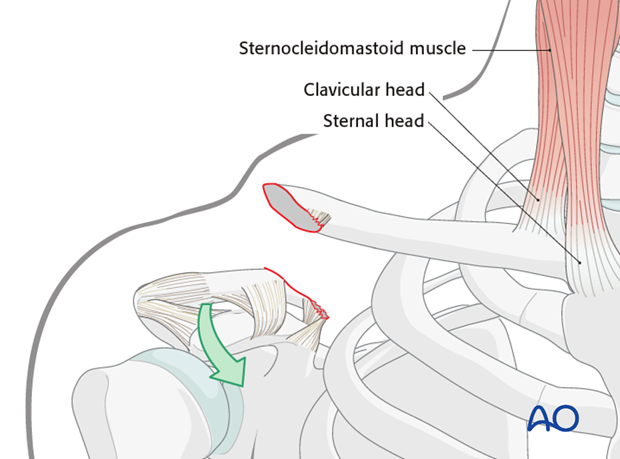

The sternocleidomastoid muscle, which inserts on the medial third of the clavicle, is not the main deforming force. The medial third of the clavicle stays in place, but the lateral 2/3 and the shoulder girdle displace downwards and forwards due to gravity. Pushing of the shoulder upward helps to reduce the lateral fragment to the medial fragment.

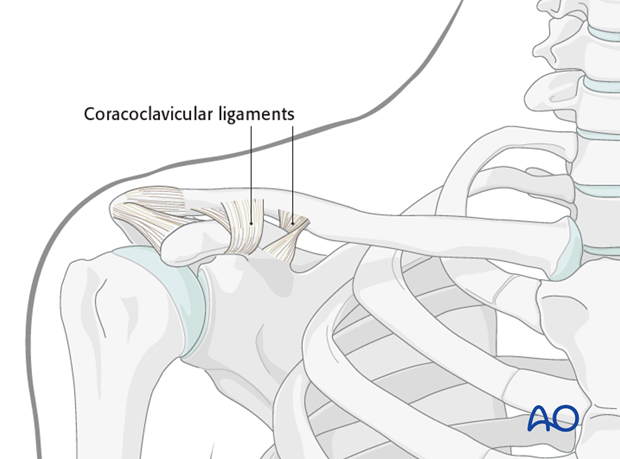

There are numerous ligamentous attachments to the clavicle. The coracoclavicular and acromioclavicular ligaments have a dominant role in maintaining the attachment of the clavicle to the upper extremity.

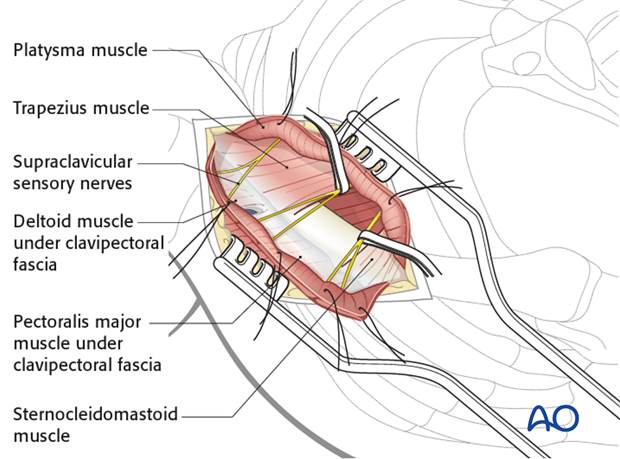

3. Skin incision

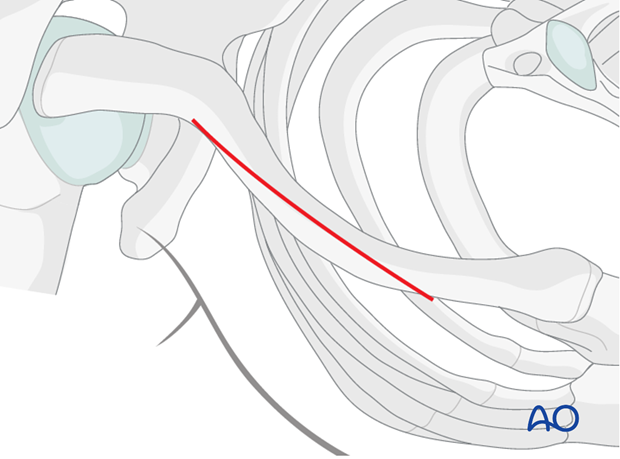

An oblique 8-10 cm incision is made just superiorly over the clavicle centered over the fracture site. This incision will work for fractures of the medial 1/3.

4. Dissection

Subcutaneous flaps are created anteriorly and posteriorly.

At the medial end of the incision, the sensory branches of the suprascapular nerve may be encountered. If so they should be identified and protected. If damaged or sacrificed, this leaves a small area of numbness inferior to the incision which patients will typically tolerate well if they are warned of this preoperatively.

However, the upper end of the cut cutaneous nerve can form a painful irritating neuroma. For this reason the supraclavicular nerve should not be sacrificed.

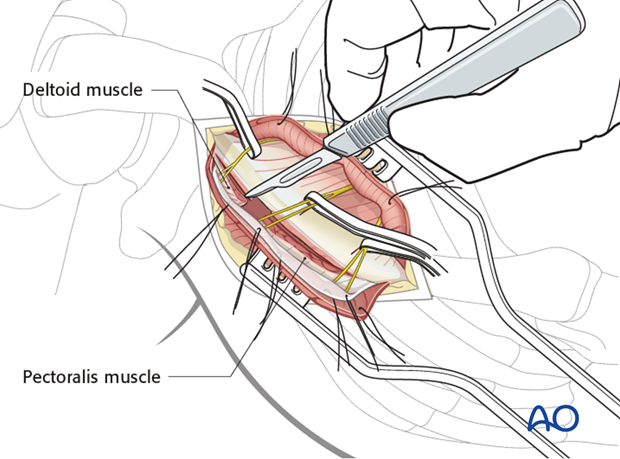

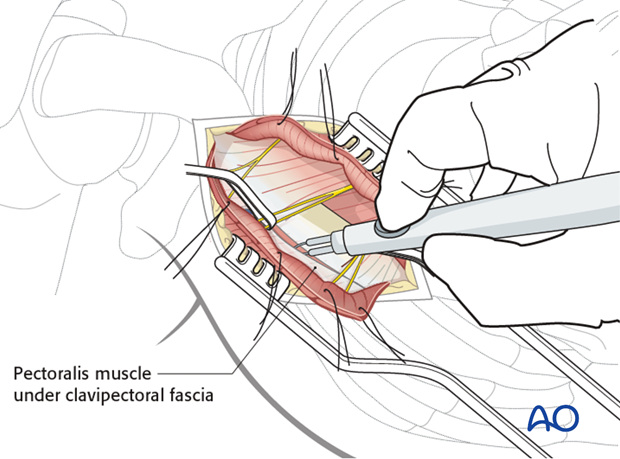

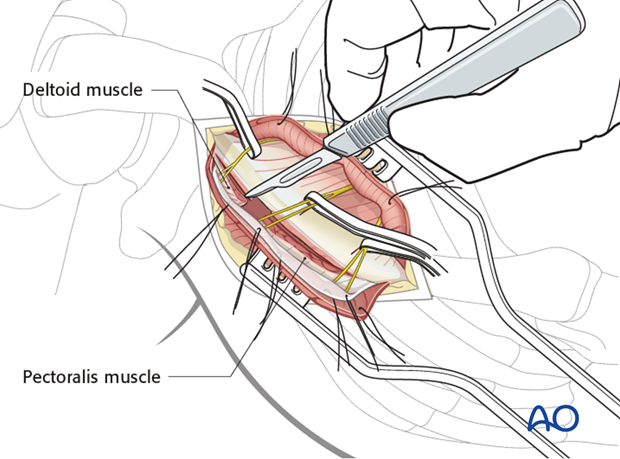

The clavipectoral fascia is incised to expose the fracture. Laterally a small area of pectoralis major muscle attachment may require reflection at the fracture site, most of the attachment of this muscle is left undisturbed. This can be performed bluntly with periosteal elevators or sharply with a blade.

Laterally, the deltoid muscle must be reflected from the lateral clavicle anteriorly and posteriorly in a contiguous sheet.

Care must be taken to preserve soft tissue attachments to all bone fragments to enable proper bone healing. Comminution of the fracture site is common. While accurate reduction of these fragments is important, it should not be at the expense of complete stripping of soft tissue. It is preferable to maintain viability of these fragments at the expense of some malreduction.

5. Closure

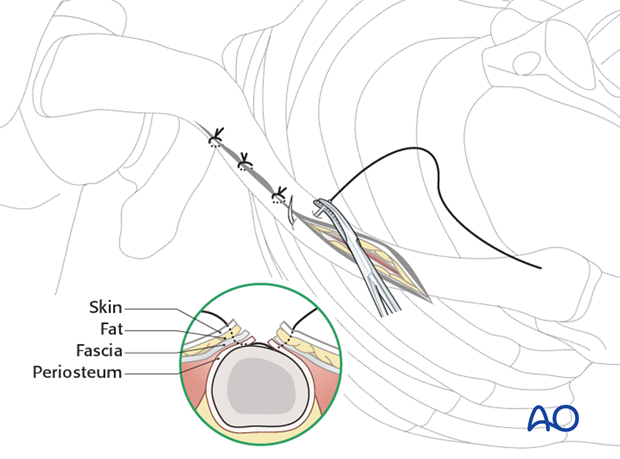

After copious irrigation of the wound the fascia and subcutaneous tissues are closed in layers.

Take great care to oppose the layers of the platysma exactly as previously cut so that no deformity of the overlying skin occurs.

Make sure that the clavipectoral fascia is closed so as to cover the underlying plate and optimize healing.

Pearl: Incorporating the cut and elevated underlying periosteum with the fascia repair will help to reduce dehiscence and strengthen closure of the fascia.

Oppose the skin with great care and avoid tension so as to end up with minimal scarring and deformity.