Late sequelae

1. Introduction

- Complications and late sequela of cranial vault/anterior skull base fractures typically include:

- Mucocele/Mucopyocele of the frontal sinus

- Osteomyelitis

- Contour deformities

- Infection of (allogeneic) grafts

- Late CSF leak

- Meningitis

These sequela may occur even decades after the initial injury and often require surgical management.

The risk for late sequela can be minimized by meticulously ensuring adequate drainage if the frontal sinus is preserved or meticulous removal of mucosa if it is obliterated. Patients with frontal sinus/anterior skull base fractures should be followed up for years.

Mucocele/Pyocele

Mucocele/pyocele is the most frequent late sequela after frontal sinus fractures and may occur many years after the accident. These complications are the result of mucosal proliferation after incomplete removal of the mucosa or inadequate drainage. Typical symptoms include pain, swelling, and globe displacement. Treatment with antibiotics may temporarily relieve the symptoms. However, due to the potentially serious complications (eg, meningitis, visual dysfunction) operative treatment should not be delayed for a long time.

If the mucocele is accessible and limited a transnasal endoscopic approach may be employed. Otherwise an open procedure should be performed.

2. Operative techniques: Open approach

Indications and limitations

The open approach is indicated whenever the pathology involves regions of the frontal sinus which can not be addressed transnasally or if reconstruction of sinus walls or frontal bone is necessary. The coronal approach allows wide exposure of the sinus and naso-orbital-ethmoidal region and it allows for craniotomy if necessary. In addition, harvesting of cranial bone grafts can be done without an additional incision.

Technique

- Coronal approach

- Exposure of the frontal sinus

- Osteotomy of anterior table of frontal sinus

- Removal of infected material

- Meticulous removal of mucosa

- Reconstruction or obliteration of the frontal sinus: The technique of reconstruction may considerably change depending on the specific problem. This is illustrated by the following collection of cases.

3. Case example: Mucocele with globe displacement

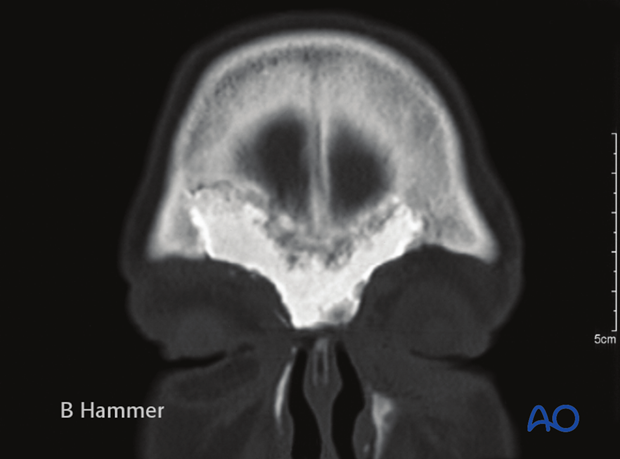

Large mucocele of the left frontal sinus causing …

… caudal/lateral displacement of the globe.

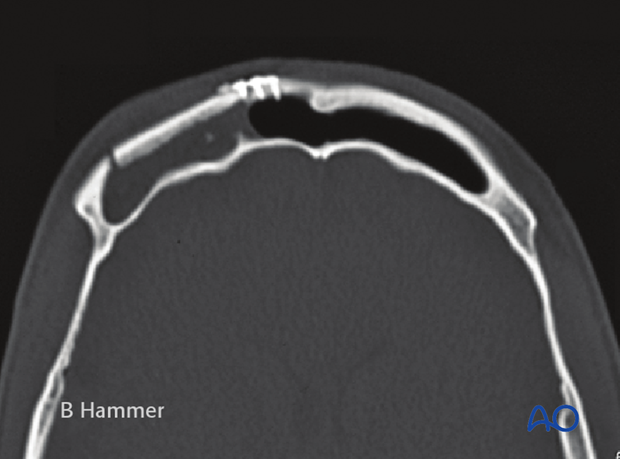

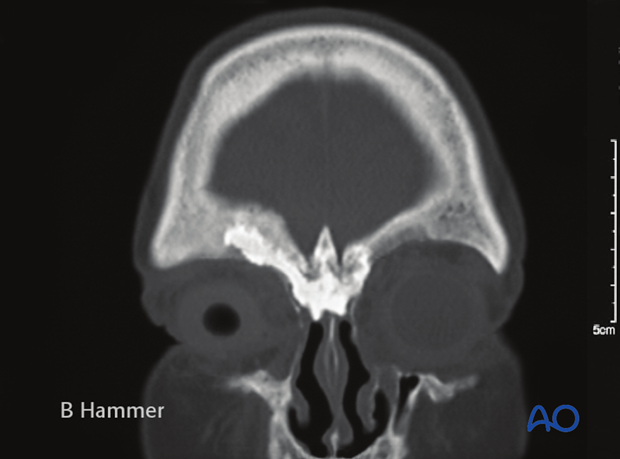

Postoperative scan showing the osteotomy used for access and repair of the mucocele. The defect in the orbital roof was reconstructed with a cranial bone graft (arrow).

Even though this mucocele could have been approached endonasally, reconstruction of the orbital roof would not have been possible.

4. Case example: Partial obliteration of the frontal sinus

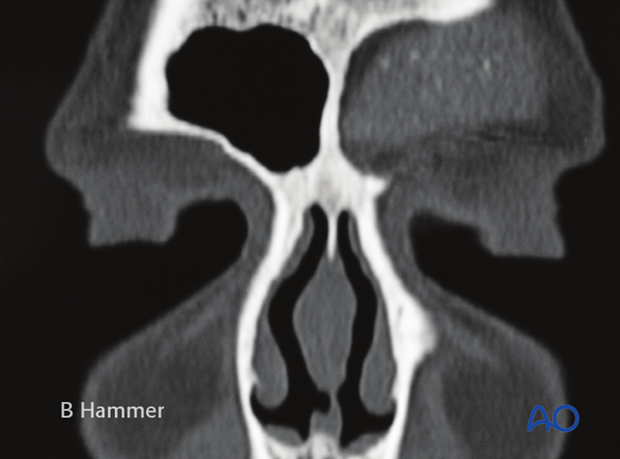

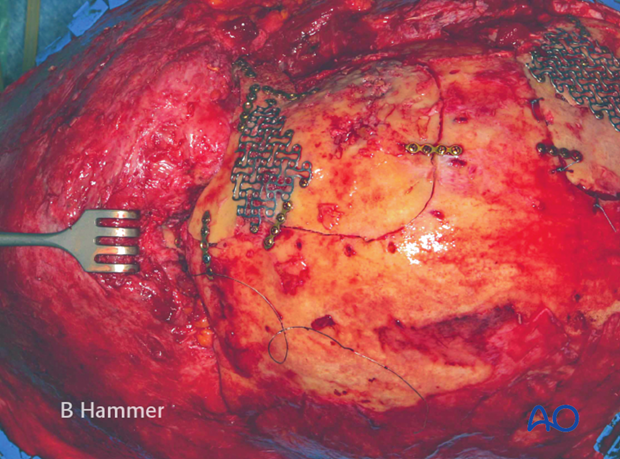

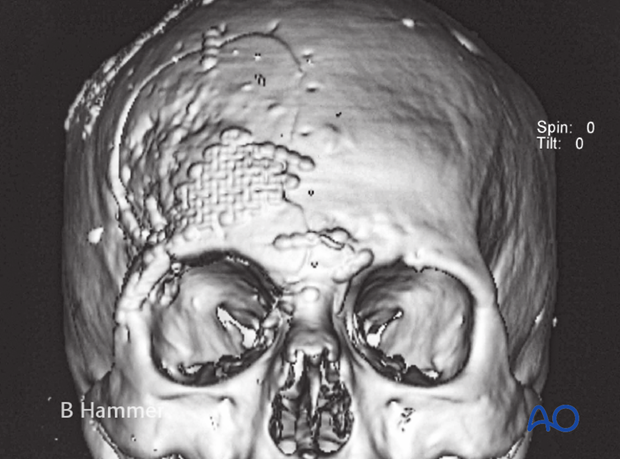

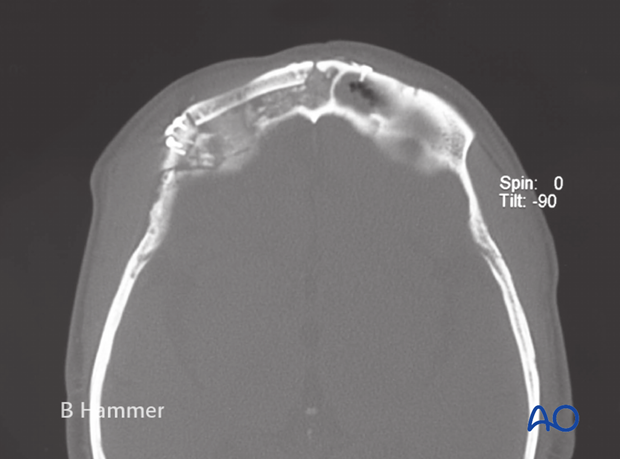

Mucocele affecting only the lateral two thirds of the right frontal sinus in a patient with previous titanium mesh reconstruction of the anterior table of the frontal sinus and recurrent infections. The drainage of the medial one third and of the left frontal sinus is intact.

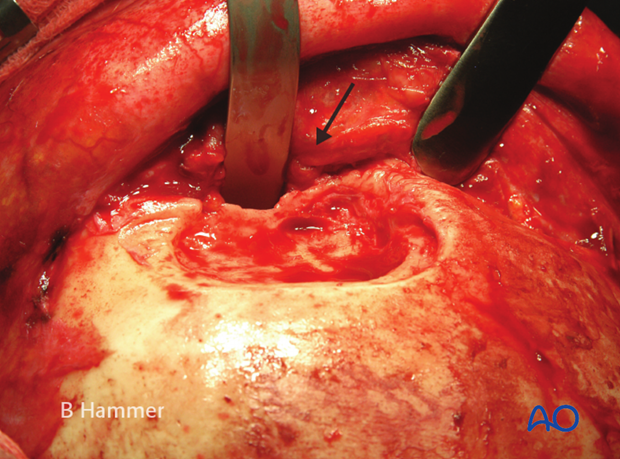

Mucocele has resorbed the orbital roof causing recurrent orbital cellulitis.

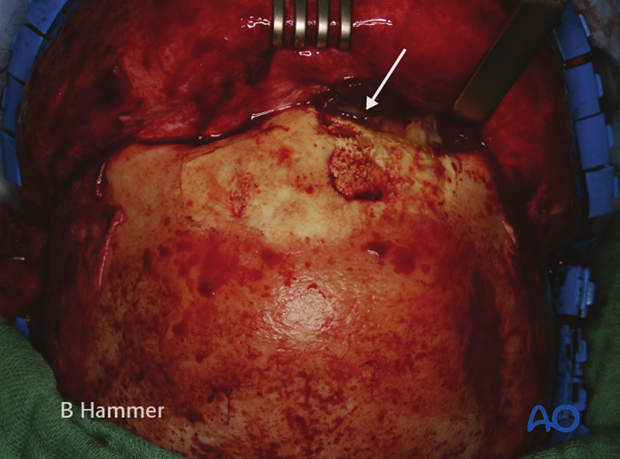

Initial repair of the frontal sinus fracture had been achieved with a titanium mesh, reconstructing the anterior table defect.

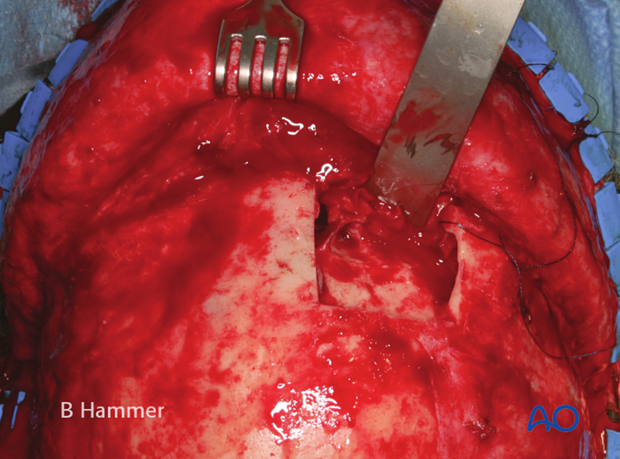

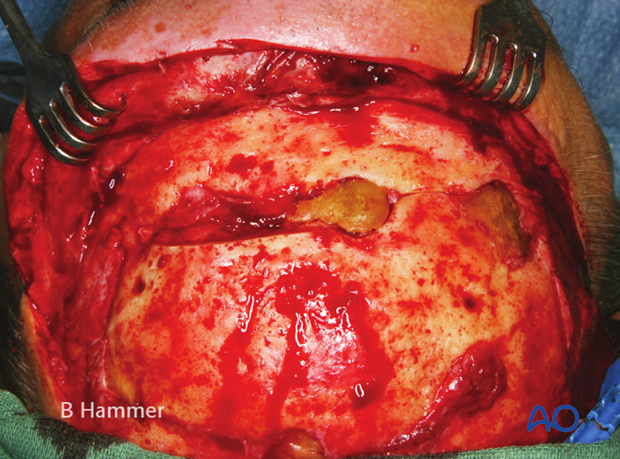

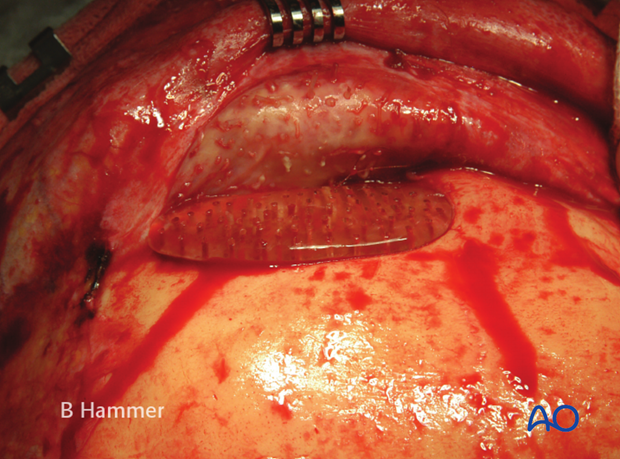

After removal of the mesh, the frontal sinus can be inspected.

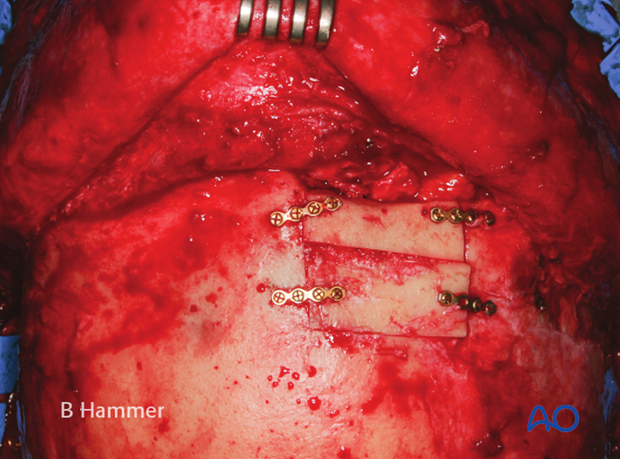

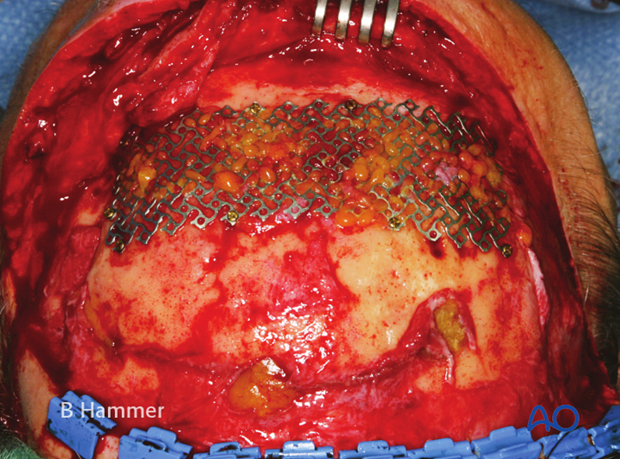

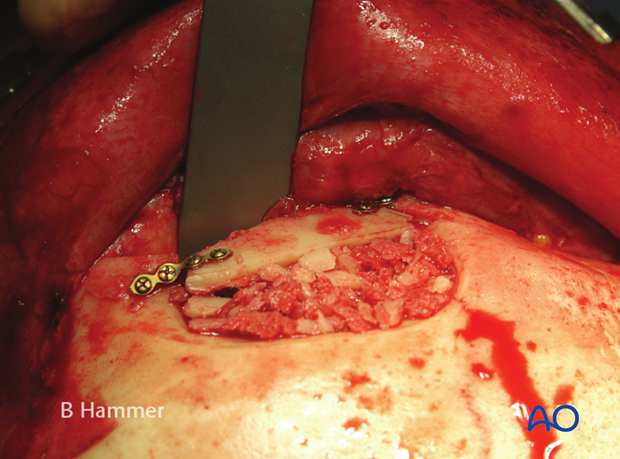

Reconstruction of the anterior table defect with bone.

In this case, only partial obliteration of the frontal sinus was done with fat and fascia, while the defect in the orbital roof and in the anterior table was reconstructed with cranial bone.

Considering the large communication between the frontal sinus and the ethmoidal sinus, partial obliteration was considered to be technically less difficult.

5. Case example: Infection of a hydroxyapatite graft

Chronic infection with recurrent fistulae 5 years after obliteration of the frontal sinus with hydroxyapatite cement. The use of hydroxyapatite cement in direct communication with the nasal cavity is not recommended due to the high complication rate.

Exposure of the cement to the nasal cavity resulted in contamination and infection of the alloplastic graft.

If hydroxyapatite is chosen for obliteration of the frontal sinus, contact to the nasal cavity must be avoided.

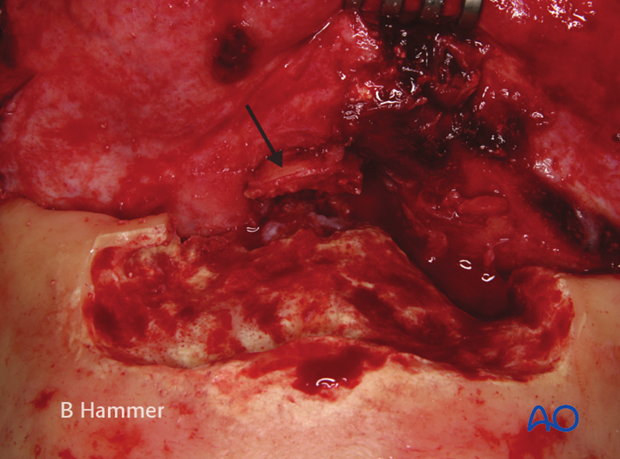

Dissolution of the graft by granulation tissue.

After removal of the graft the nasal root (see arrow) is mobile.

Stabilization of the nasal root and reconstruction of the supraorbital rim with cranial bone.

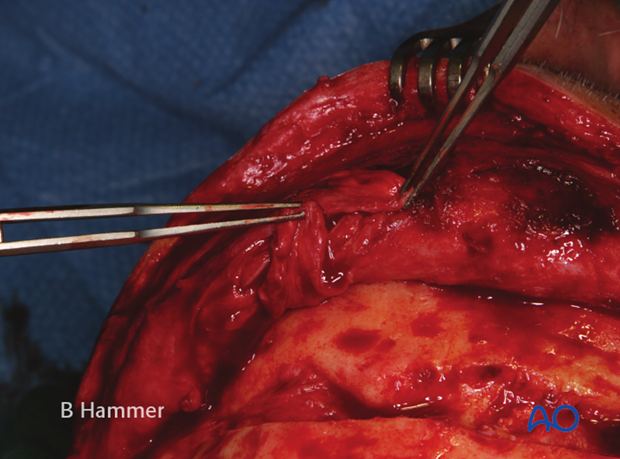

Communication to the nasal cavity is sealed with fascia (arrow).

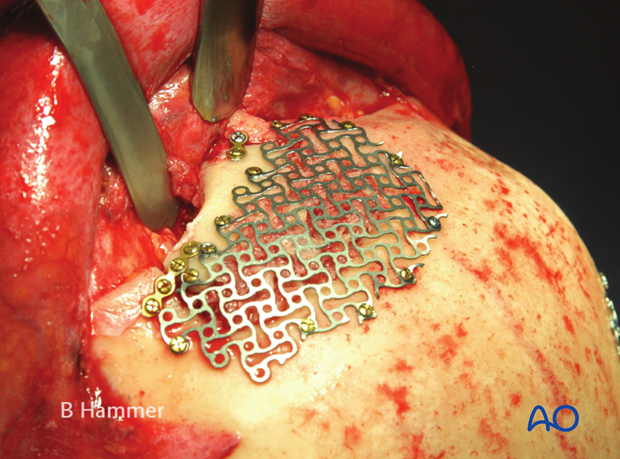

The frontal sinus cavity is obliterated with fat and the anterior table is reconstructed with titanium mesh.

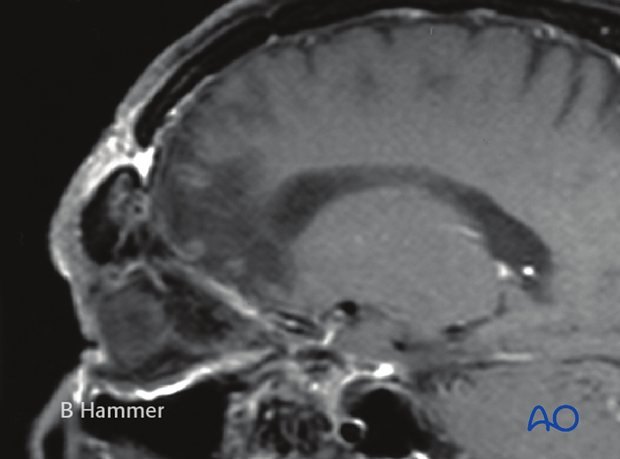

6. Case example: Infection of a PMMA graft causing recurrent fistulae

Patient 20 years after extended frontal sinus fracture. In the initial repair, obliteration of defects was achieved with PMMA. Ten years after the accident, recurrent fistulization occurred. Repeated local excisions were unsuccessful.

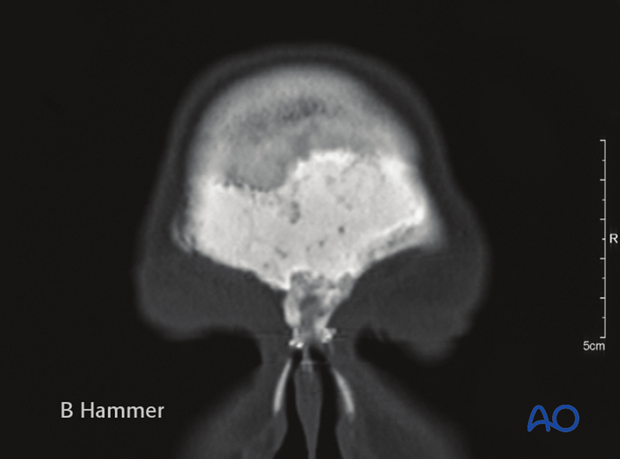

MRI shows a defect in frontal bone communicating with the fistula.

Intraoperative view showing the PMMA graft embedded into granulation tissue.

After debridement the contour of the bone is restored with a titanium mesh and the defect is filled with fat.

The fistula is closed from the inside with a rotational pericranial flap.

Uneventful healing with a slightly depressed scar after 6 months.

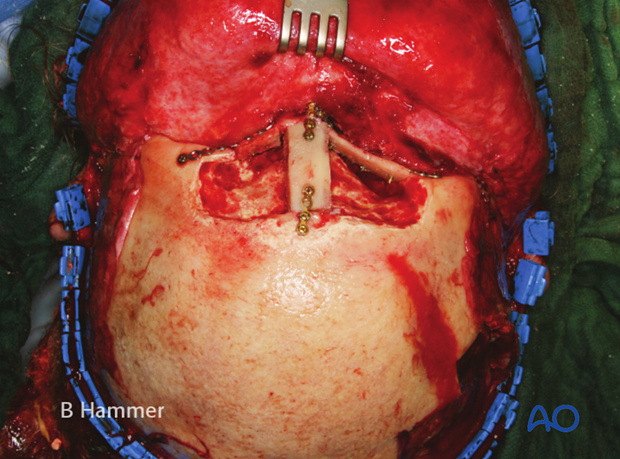

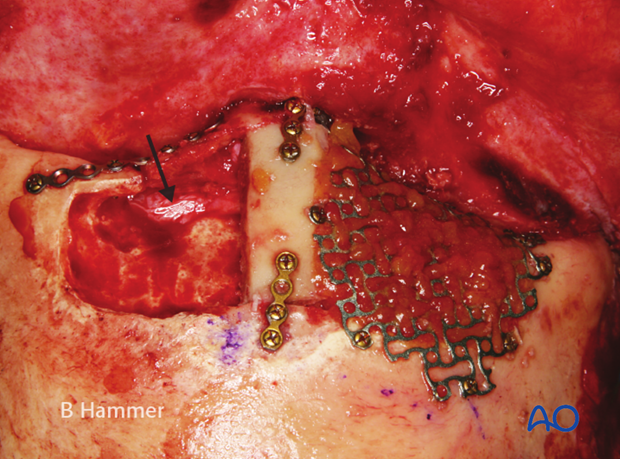

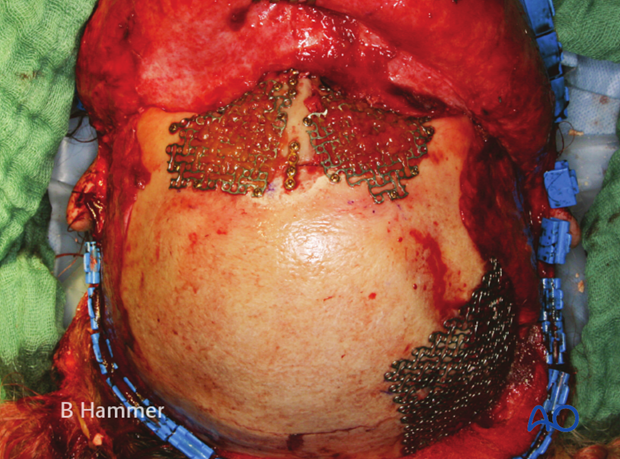

7. Case example: Infection of allogenic graft, causing swelling and chronic headache

Chronic infection of the left frontal sinus after obliteration with a polymeric inlay causing swelling and chronic headache.

Exposure shows that the graft is embedded in granulation tissue.

After explantation and cleaning, the supraorbital rim is missing (arrow) and will be replaced with cranial bone.

The supraorbital rim was reconstructed with cranial bone and the defect obliterated with cortical cancellous bone chips.

The anterior table is replaced with a titanium mesh.

Alternatively, the anterior table can also be reconstructed with cranial bone. See case “partial obliteration”

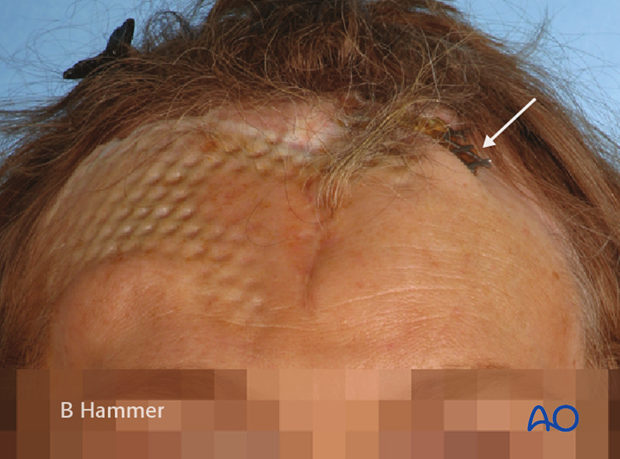

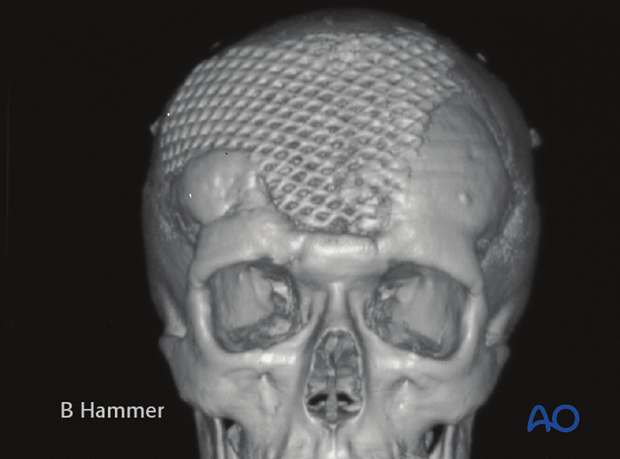

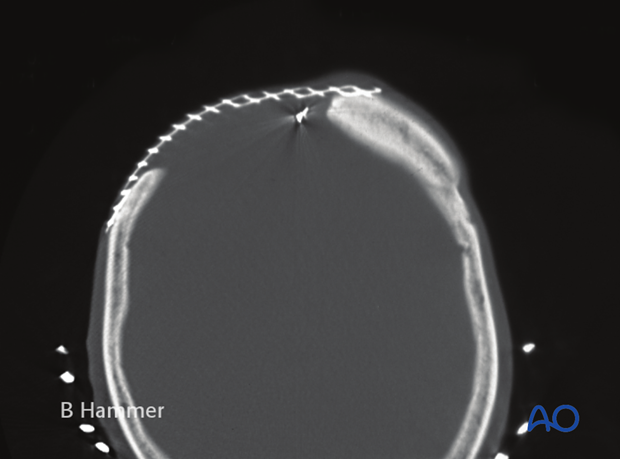

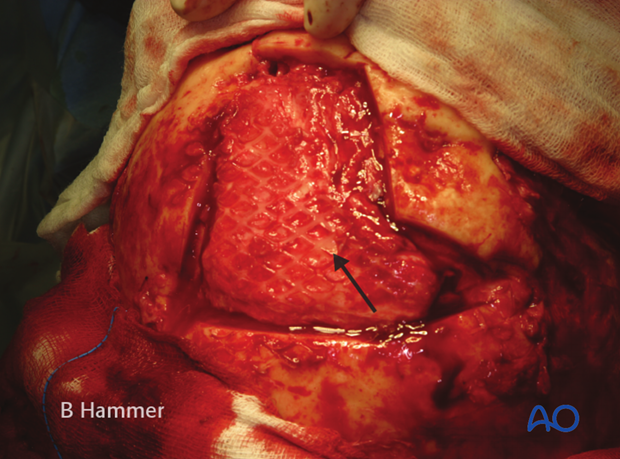

8. Case example: Exposure of a titanium mesh through the skin

This patient fell from a horse resulting in a extended frontal sinus and frontal bone fracture. Initial repair was done with PMMA which had to be removed due to an infection after one year. Secondary repair was done with a titanium mesh which was just laid onto the bone without fixation. After two years, the mesh began to perforate through the skin (arrow).

Wide-meshed titanium mesh floating on the defect without fixation.

Dead space below the mesh resulted in indentation of the skin (see also previous clinical photograph).

The defect in the frontal bone after removal of the mesh. The underlying dura (see arrow) is covered by thick scar.

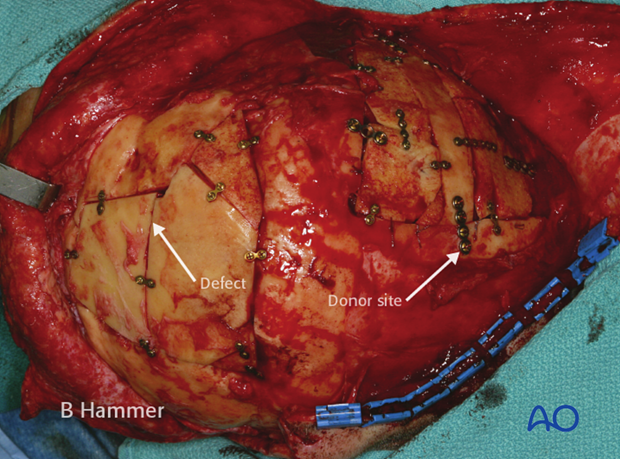

Reconstruction of the defect was done with split cranial bone (outer table) taken as a full-thickness graft from the posterior half of the skull. The donor site defect was reconstructed with internal table.

Uneventful healing after 3 months. Note the thinning of the skin of the right forehead due to the taking of pericranial flap during initial repair.

9. Case example: Osteomyelitis of the supraorbital rim with fistulization

This patient sustained a motor vehicle accident with a right frontal sinus and cranial base fracture requiring cranialization of the frontal sinus. Ten years after the accident, recurrent fistulization in the area of the glabella occurred. Despite several revisions using a local incision fistulization did not stop.

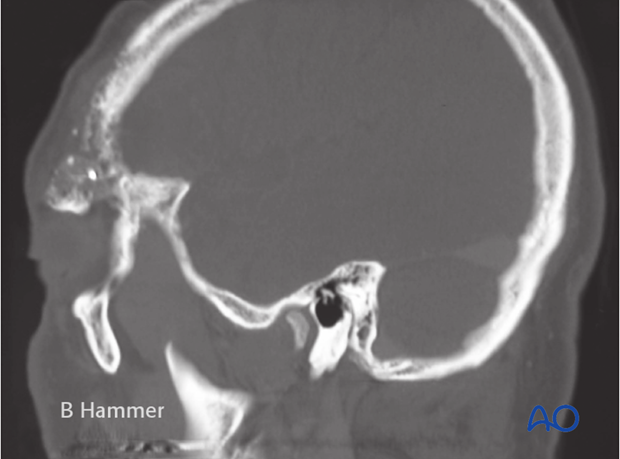

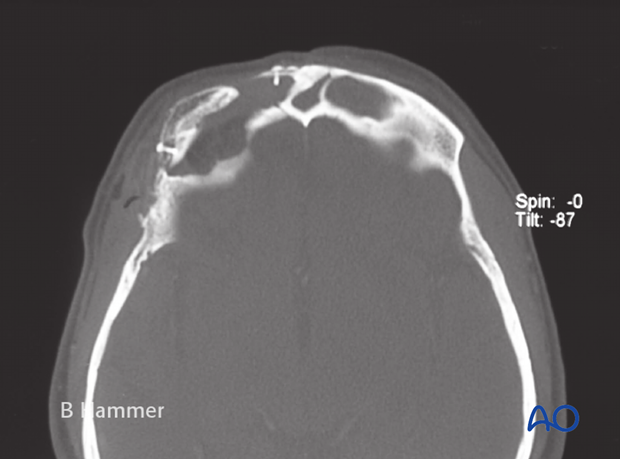

CT shows osteomyelitis and partial resorption …

… of the right supraorbital rim.

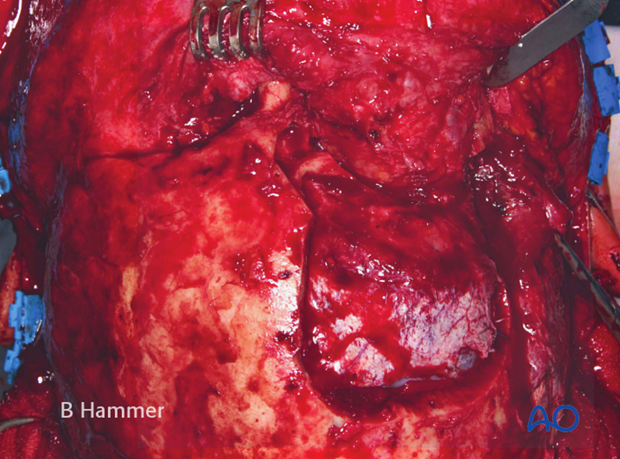

Intraoperative view after resection of the affected supraorbital rim. Due to previous cranialization of the frontal sinus, a formal craniotomy was done to protect the dura.

The supraorbital rim was reconstructed with full thickness cranial bone taken from the posterior part of the skull.

Postoperative x-rays demonstrating …

… anatomical reconstruction of the supraorbital rim.

Postoperative clinical view. Elimination of the osteomyelitis allows for spontaneous healing of the fistula.

10. Operative techniques: Transnasal endoscopic approach

Indications

Recent advances in endoscopic equipment and techniques (frontal sinus instrumentation, navigation, intraoperative CT) has greatly expanded the scope of access for endoscopic sinus surgeons.

The preferred technique for treatment of paranasal sinus mucoceles is endoscopic drainage into the nasal cavity. If a mucocele can be drained into the nasal cavity there is no need for any further intervention. The mucocele simply becomes an accessory sinus. This avoids the need for external incisions, hardware application, or bone grafting.

Frontal sinus endoscopic surgical techniques are among the most difficult endoscopic sinus procedures and should only be attempted by those comfortable doing them.

Limitations

Mucoceles inaccessible through the paranasal sinuses can not be accessed via an endonasal approach. Furthermore, mucoceles associated with contaminated hardware/implants generally can not be managed endoscopically.

Technique

A complete review of endoscopic surgical technique is beyond the scope of the Surgery Reference. However, general principles for endoscopic drainage of paranasal sinus mucoceles will be covered.

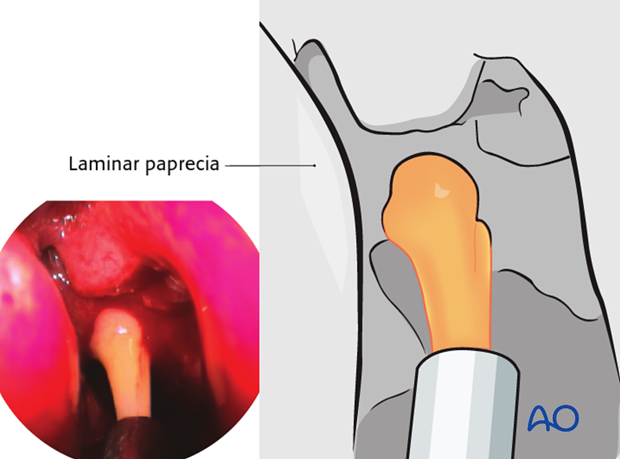

Most patients will require an endoscopic ethmoidectomy and possible maxillary antrostomy. Mucoceles emanating from the frontal sinus usually enlarge the sinus ostia making access less challenging.

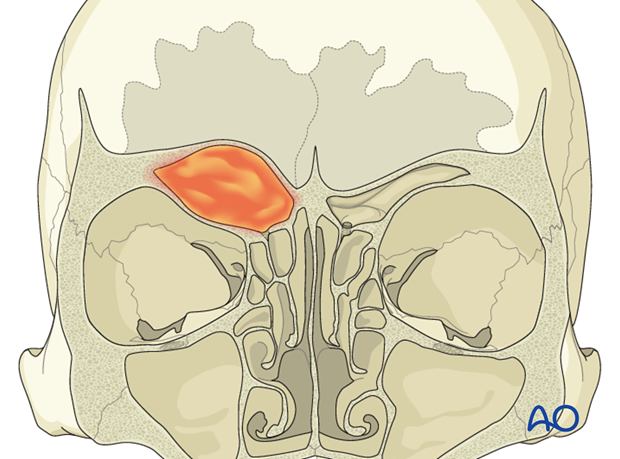

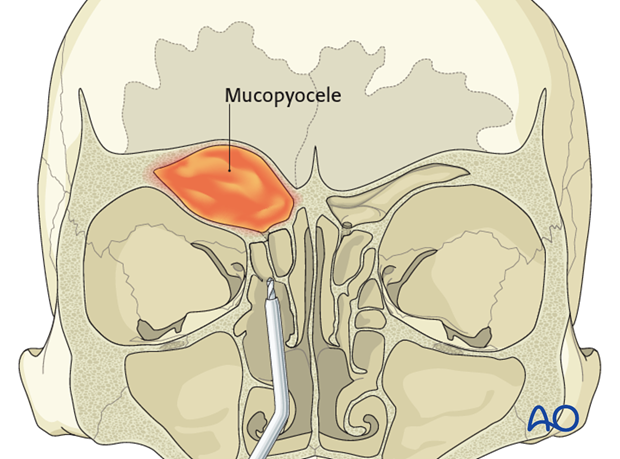

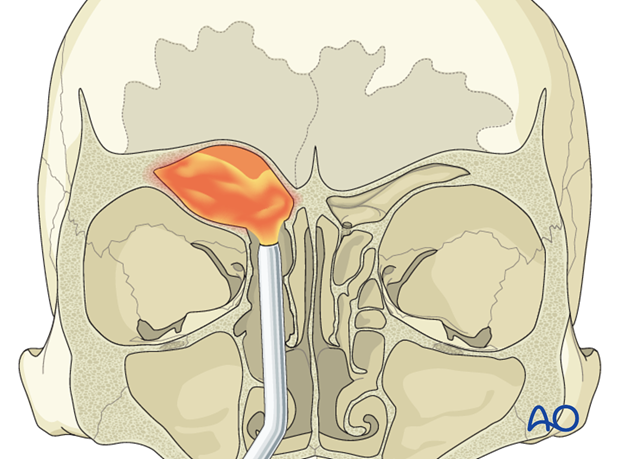

This illustration demonstrates a frontoethmoid mucocele displacing the orbital content inferiorly. Dehiscence into the anterior fossa is not a contraindication for transnasal endoscopic drainage.

A complete ethmoidectomy has been performed to allow for drainage of the mucocele. It is important to completely remove all ethmoid air cells. This minimizes the risk of recurrent obstruction and mucocele formation.

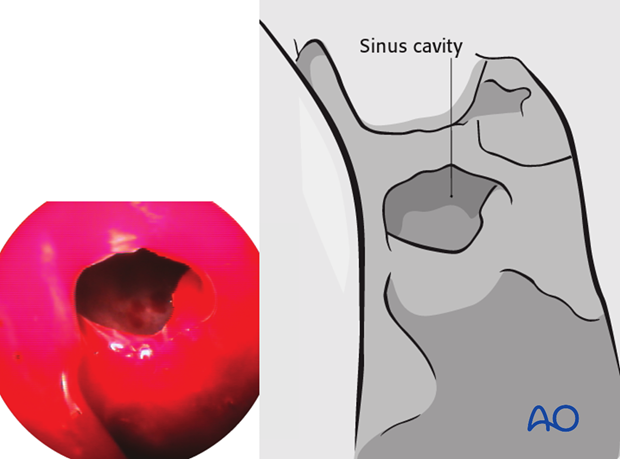

Resection of the bone on the inferomedial aspect of the mucocele provides a pathway for drainage of the mucocele into the nose. Intraoperative navigation assists the surgeon to more safely enlarge the opening without violating the orbital or intracranial cavities. The opening should be made as large as possible to minimize the risk of postoperative stenosis and obstruction, which can result in recurrent mucocele formation.

Case example I

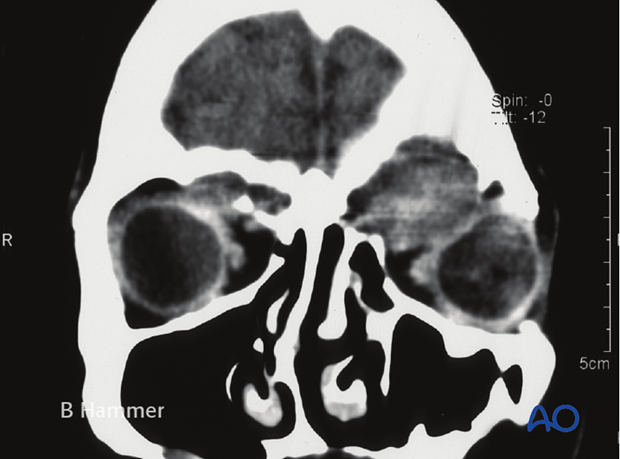

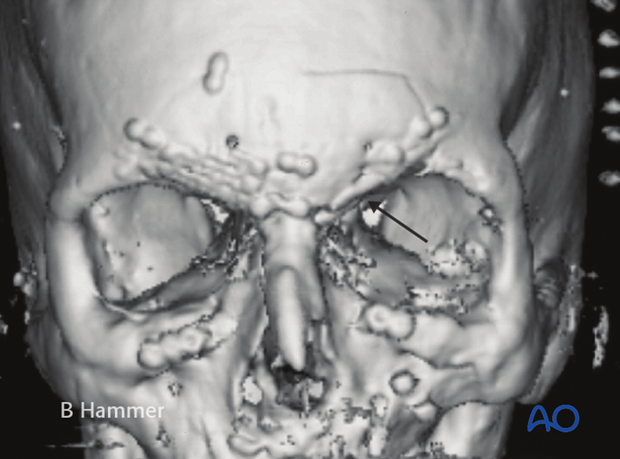

A 60 year old female with frontoethmoid mucocele with proptosis, hypophthalmos, in an only seeing eye. The mucocele has also resulted in:

- A bony orbital deformity

- Globe compression and deformity

While there appears to be very limited access from the nasal cavity, this is quite adequate for transnasal endoscopic drainage of the mucocele.

Endoscopic photograph demonstrating decompression of the mucocele and suctioning of its contents.

Endoscopic transnasal view from the nose into the mucocele.

Two years postoperatively, the mucocele cavity continues to drain and be well aerated. The bony deformity has also improved significantly.

The hypophthalmos and proptosis have resolved.

Case example II

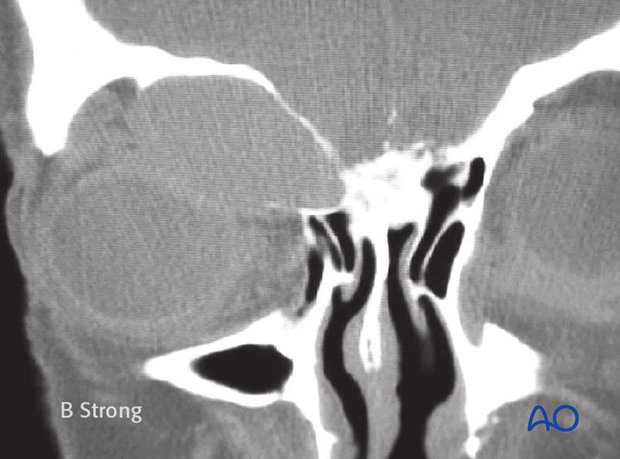

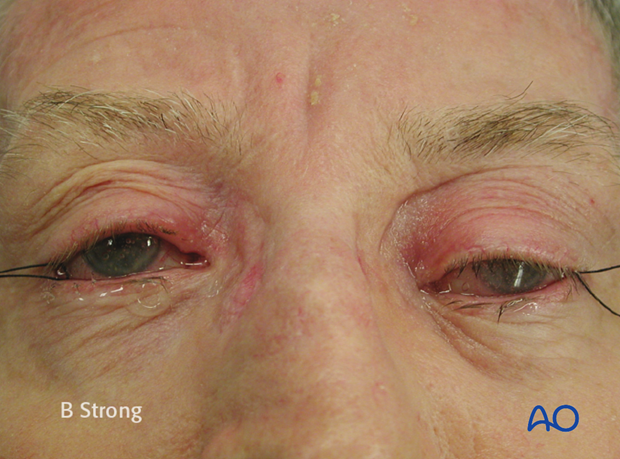

70 year old male with posttraumatic frontoethmoid mucocele, hypophthalmos and exophthalmos.

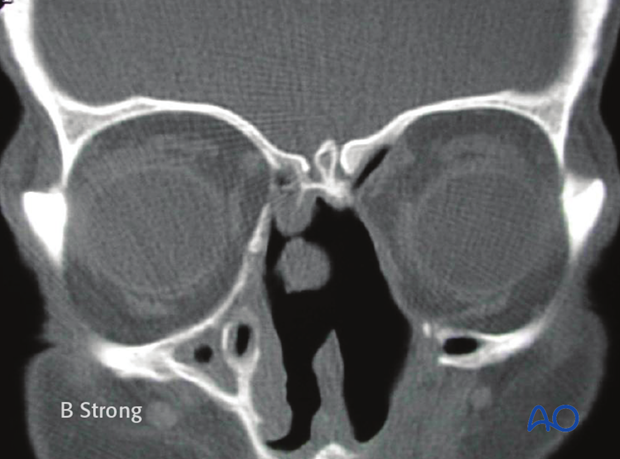

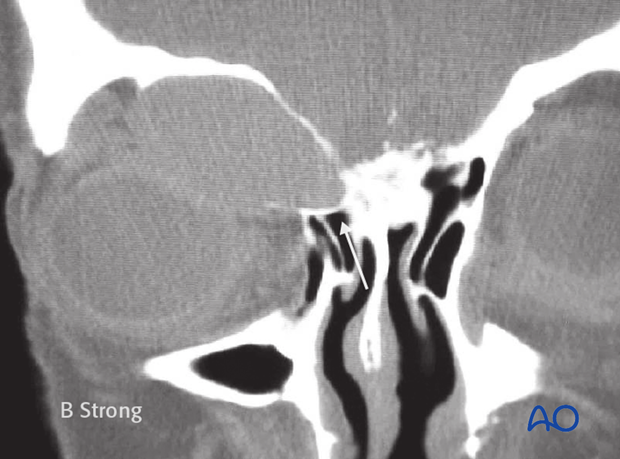

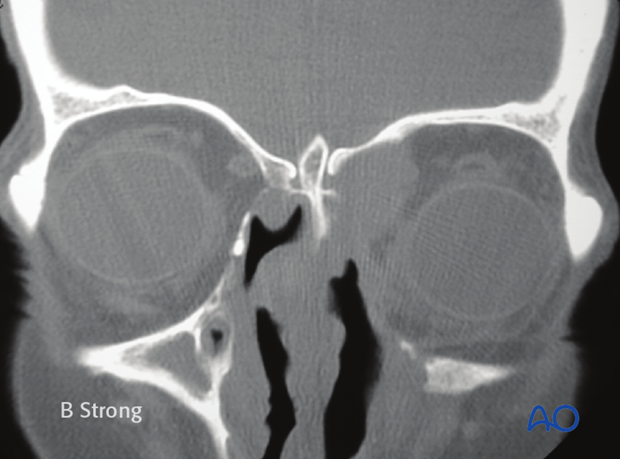

Coronal CT scan of the same patient.

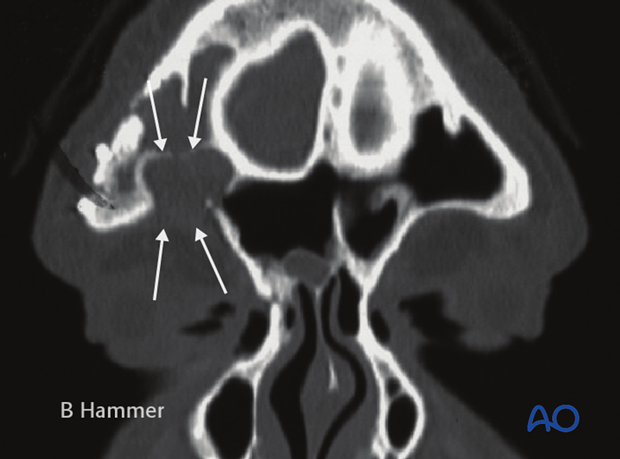

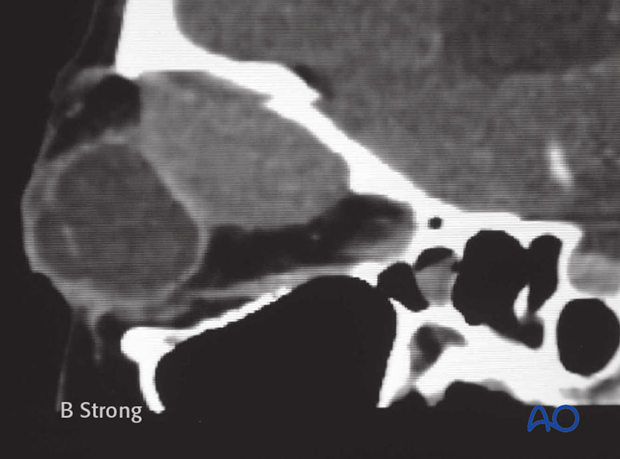

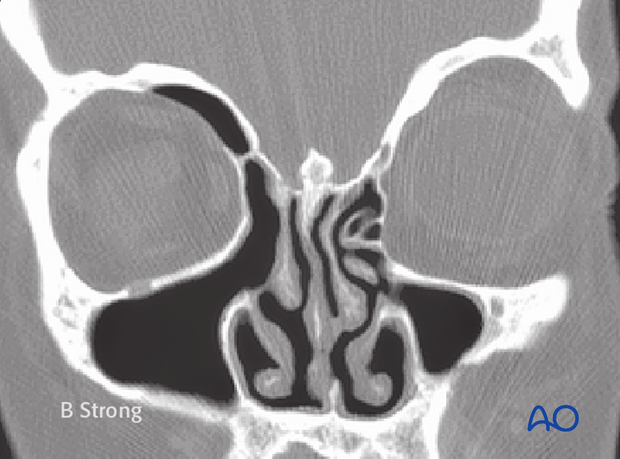

Postoperative CT scan demonstrating complete left ethmoidectomy and drainage of the mucocele.

(Note: Septal perforation seen on CT scan was present prior to endoscopic mucocele decompression.