Frontal sinus fracture, posterior table

Anatomy

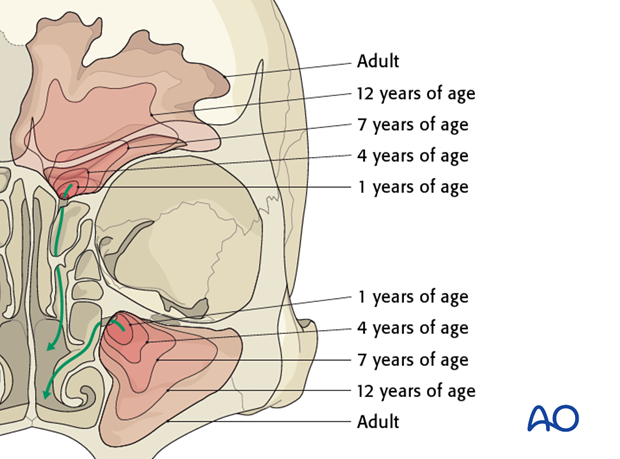

Evolution over age

The frontal sinus is generally absent at birth. At one year the anterior ethmoid air cells begin to invade the frontal bone. Frontal sinus growth is then complete at approximately 15 years of age.

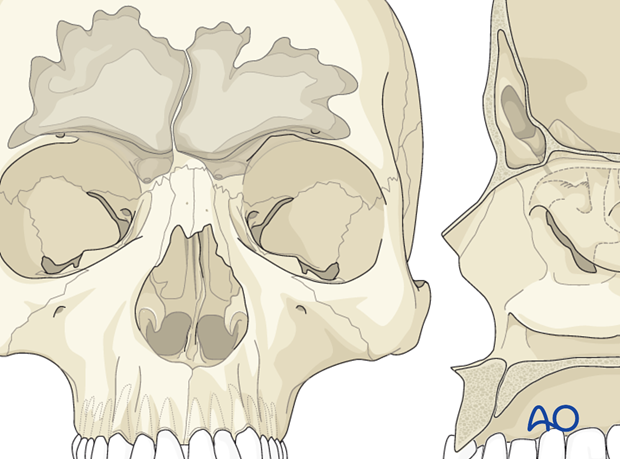

The frontal sinus is irregularly shaped and scalloped at its margins. Asymmetry of the sinus is the rule rather the exception (10% of individuals have a unilateral sinus, 9% of individuals have a rudimentary or absent sinus).

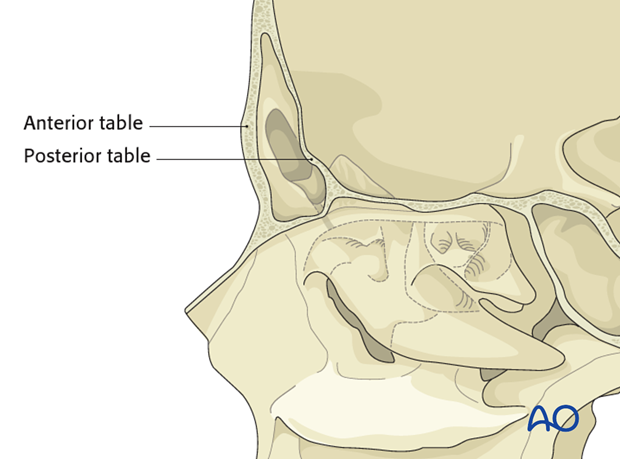

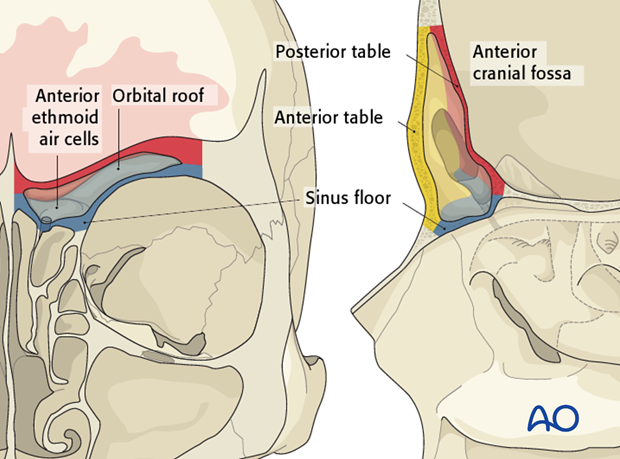

Dimension of tables

The anterior table is thick (2-12 mm) and the posterior table is thin (0.1 – 4 mm).

Anatomic relationships

The frontal sinus has several critical anatomic relationships. These include:

Sinus floor -> orbital roof/anterior ethmoid air cells

Posterior table -> anterior cranial fossa

Anterior table -> frontal contour

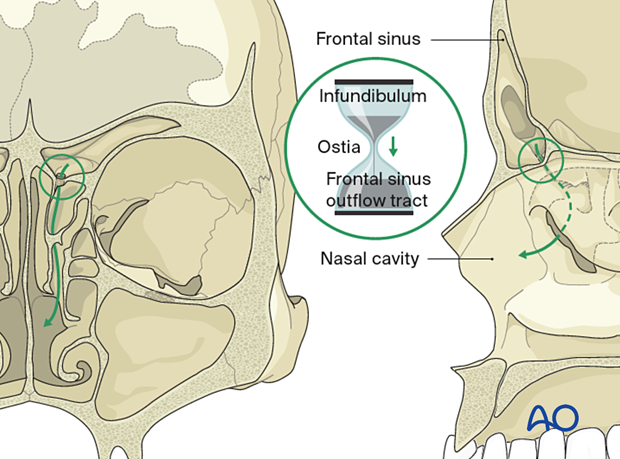

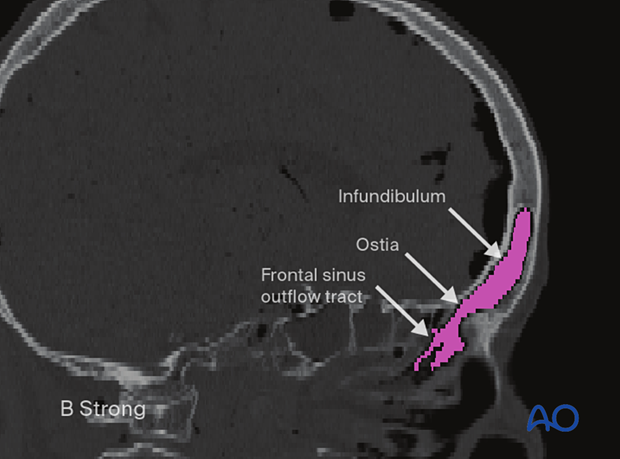

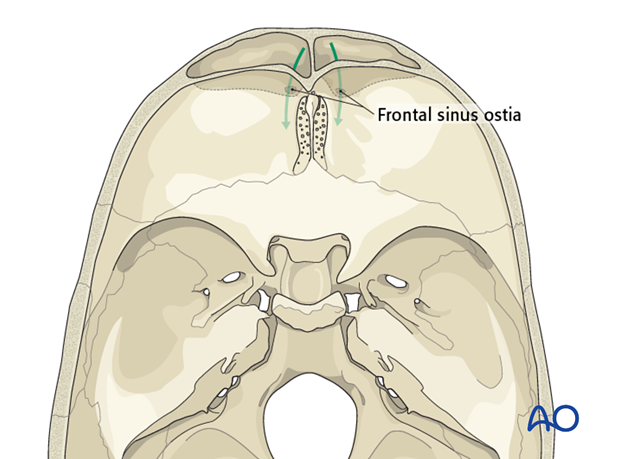

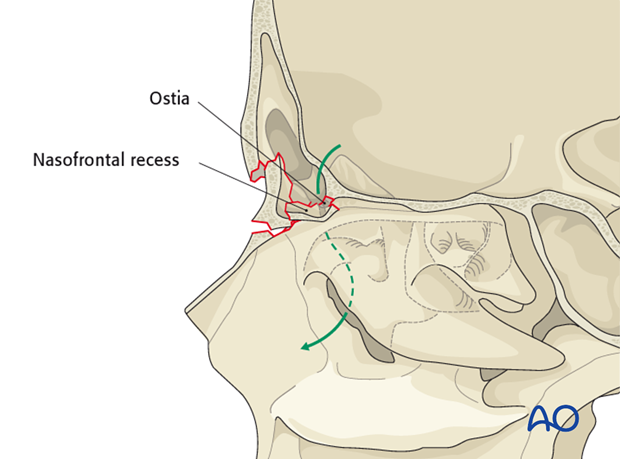

Drainage

The frontal sinus drains via a small outflow tract into the ethmoid sinus/nasal cavity. The outflow tract is hour-glass shaped with the true ostium (3-4 mm) at the narrowest portion.

The infundibulum is above and the frontal recess is below.

Each frontal sinus drainage pathway is located in the posterior, inferior, and medial portion of the sinus.

Frontal sinus fractures

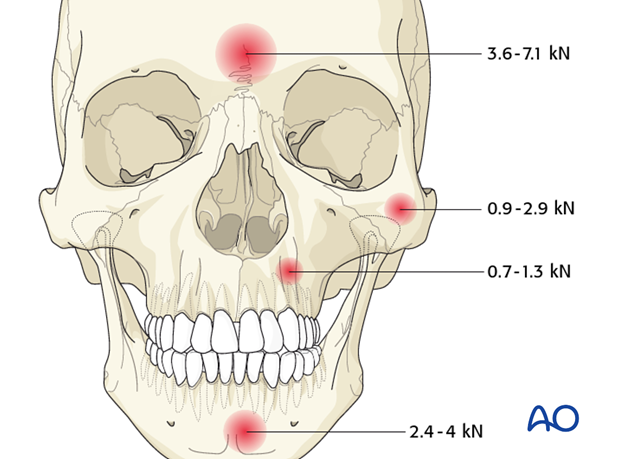

The anterior wall of the frontal sinus is thick and resistant to injury. It requires greater force to fracture than any other facial bone (3.6 – 7.1 kN, Nahum AM (1975) The biomechanics of maxillofacial trauma. ClinPlastSurg; 2:63).

The majority of frontal sinus fractures are the result of high velocity impacts such as motor vehicle accidents, assaults and sports injuries. Patients who sustain frontal sinus fractures often have associated facial fractures and systemic injuries.

The goal of frontal sinus fracture treatment is to create a safe sinus, restore facial contour, and avoid short and long term complications.

Epidemiology

Frontal sinus fractures are relatively uncommon and account for only 5-15% of maxillofacial fractures with a preponderance of male patients.

The most common frontal sinus fractures involve a combination of the anterior and posterior tables with or without frontal recess involvement (about 2/3).

Isolated anterior table fractures account for only approximately 1/3.

Isolated posterior table fractures are extremely uncommon (< 1%).

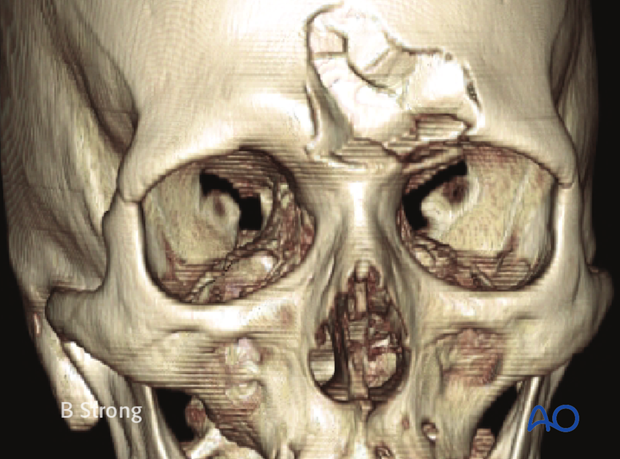

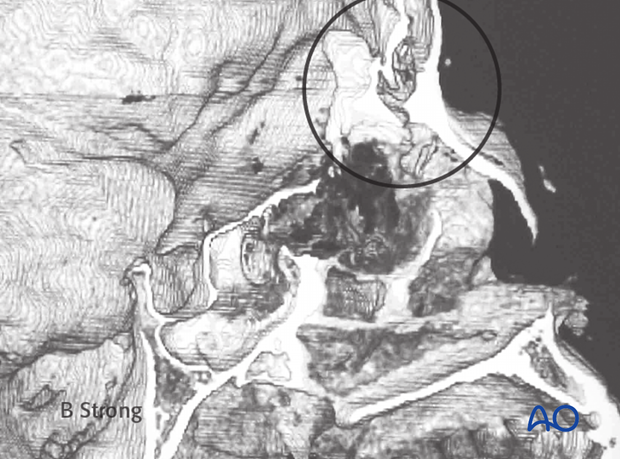

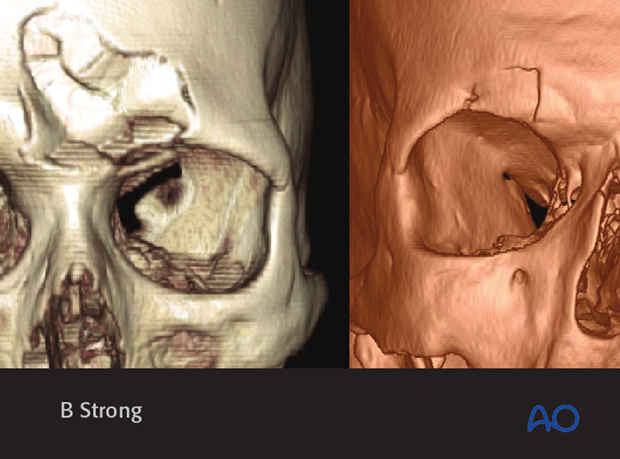

This 3D CT reconstruction shows an isolated anterior table fracture.

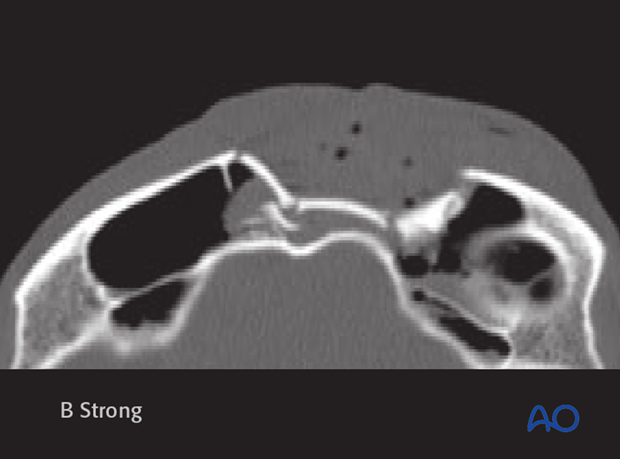

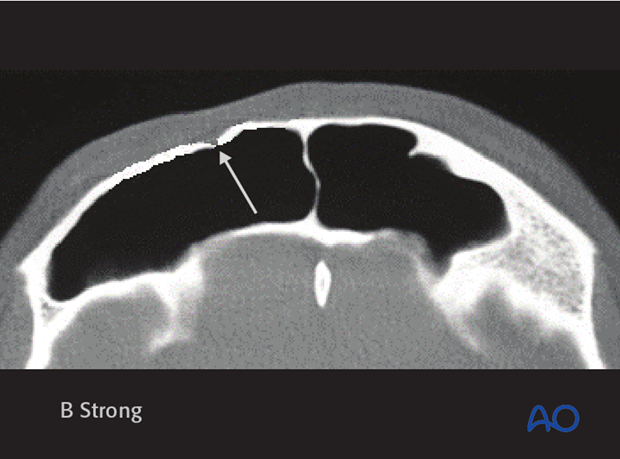

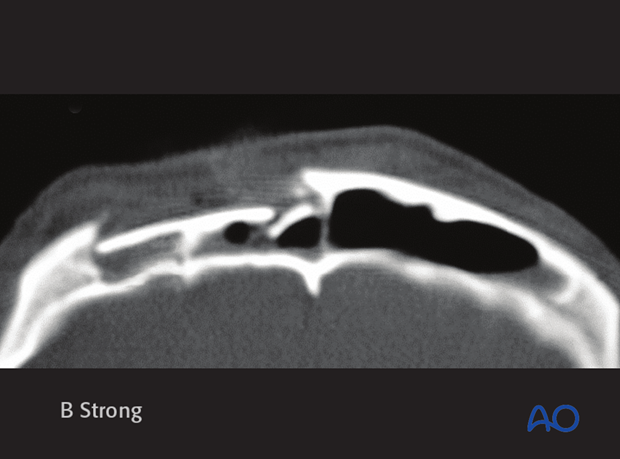

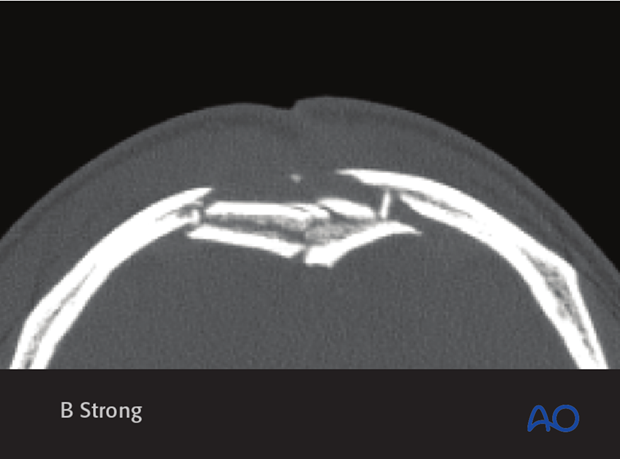

Axial CT slice of the same patient.

Clinical evaluation

A focused exam of the frontal sinus should include evaluation for any contour deformity and/or frontal lacerations and neurosensory deficits. Conscious patients should be questioned for the presence of clear nasal drainage or salty posterior nasal drainage that might be indicative of a CSF leak.

Examination of deep wounds should be performed under sterile technique, as these can be through and through injuries. The prognosis for such severe injuries is significantly worse and more aggressive management is indicated.

A high resolution CT scan with axial, coronal, sagittal and 3-D reconstruction is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Radiologic diagnosis: CT scan

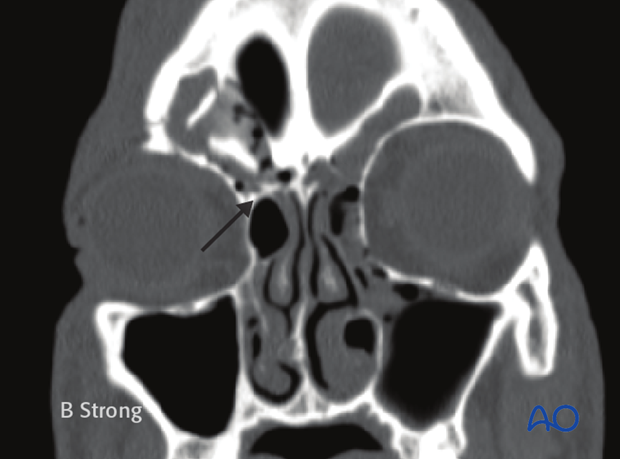

Coronal CT images can be used to document frontal recess injuries.

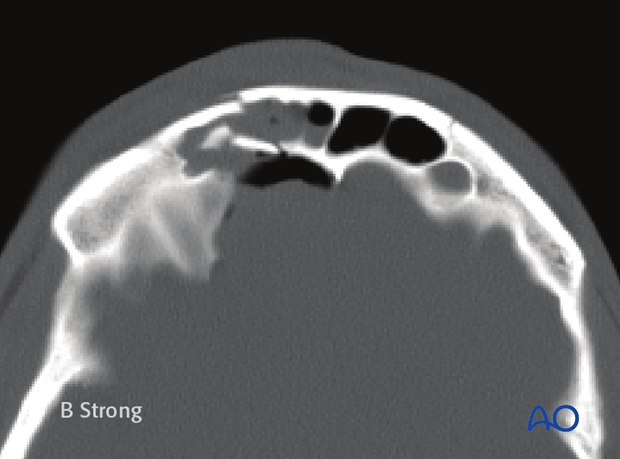

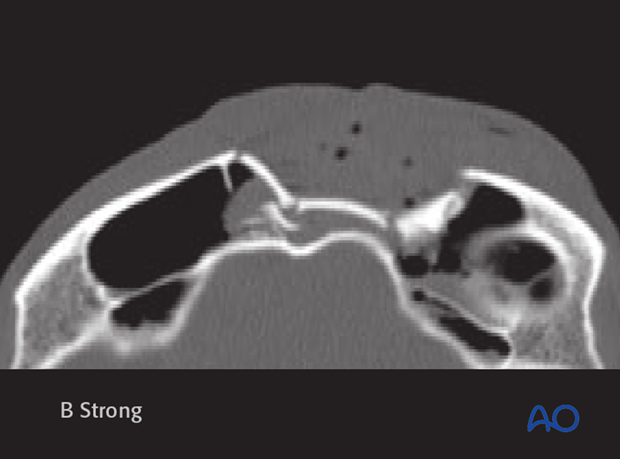

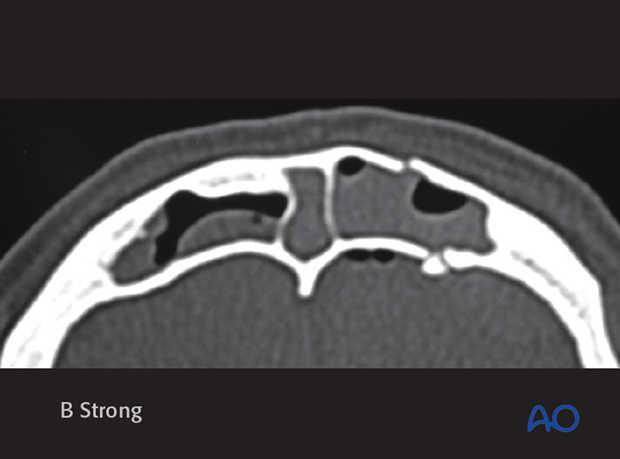

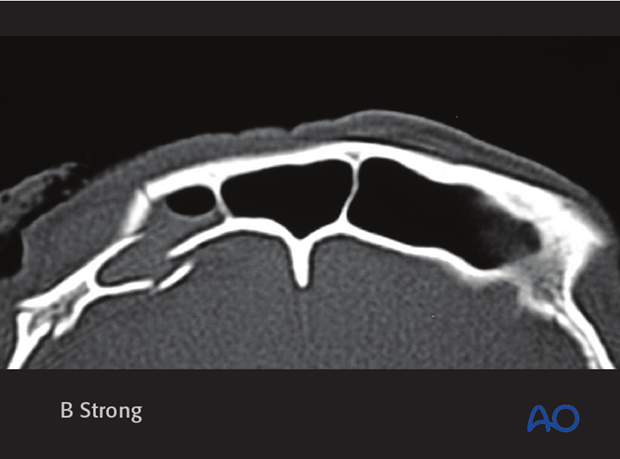

Axial CT images can be used to document anterior and posterior table injuries.

Sagittal CT images can be used to document frontal recess, anterior table and posterior table injuries.

3-D reconstruction can be used to document the spatial orientation of the displaced bone fragments.

Classification

Frontal recess involvement

A frontal recess injury involves the floor of the frontal sinus and the outflow tract. It may also involve the anterior skull base.

Anterior table fractures

Fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus vary from minimally displaced to severely displaced/comminuted depending upon the severity of the trauma and size of the sinus.

Minimal displacement

Less severe trauma may result in fractures of the anterior table which are minimally (as illustrated) or nondisplaced.

Moderate displacement

As the traumatic force increases, fracture segments are displaced more significantly.

Severe comminution

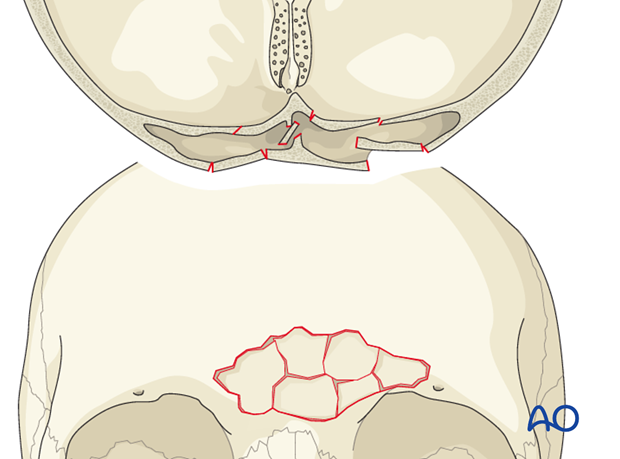

The most severe anterior table injuries result in comminution of the anterior table bone.

Posterior table fracture

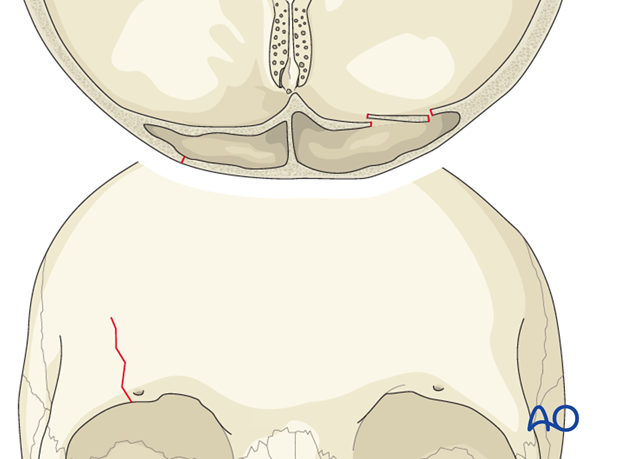

Posterior table fractures carry a higher risk of intracranial injury because they create a communication with the intracranial space. The degree of fracture displacement gives some insight into the severity of the injury. While there is no commonly agreed upon classification for displacement, many authors have used the width of the posterior table (0.1 mm – 4 mm) as a “measuring stick” to describe displacement because it is readily visible on axial CT-scans.

Isolated posterior table fractures are extremely uncommon.

Small displacement

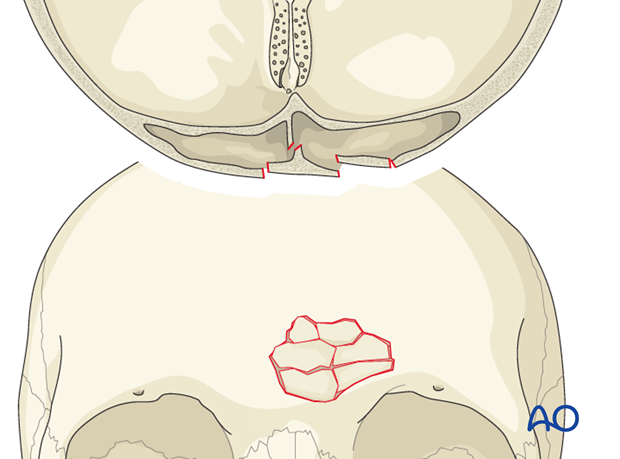

Less severe posterior table injuries may result in minimal or no displacement.

Large displacement

More severe injuries often result in displacement and/or comminution of the posterior table.

Moderate to severe comminution

The most severe injuries result in severe comminution of both the anterior and posterior tables, with an increased risk of intracranial injury.

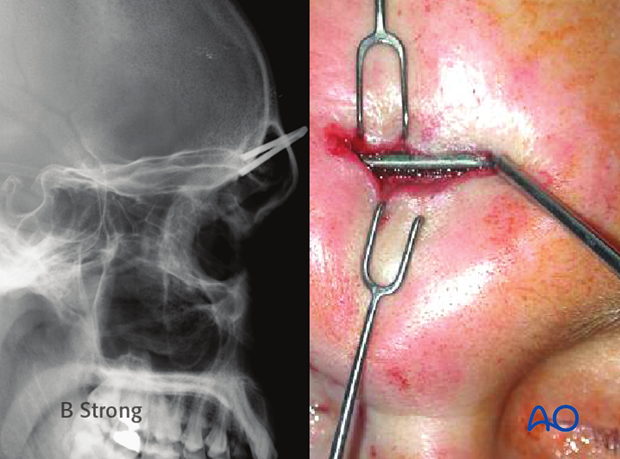

Penetrating injury

Penetrating injuries can result in either anterior table or anterior/posterior table fractures, with varying degree of comminution. These injuries can be quite focal and endoscopy can be helpful in delineation of the surgical management required.

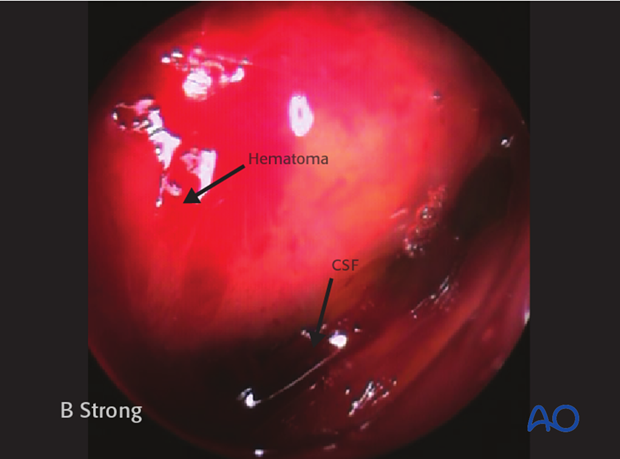

Endoscopic evaluation of penetrating injuries

A 1.0 to 1.2 cm skin incision is placed midway between the medial canthus and the glabella. The incision should be 1 cm inferior to the brow to avoid injury to the supratrochlear neurovascular pedicles. A small gull-wing-shaped incision can be used to avoid scar contracture. Electrocautery on a low setting can be used to expose the underlying bone.

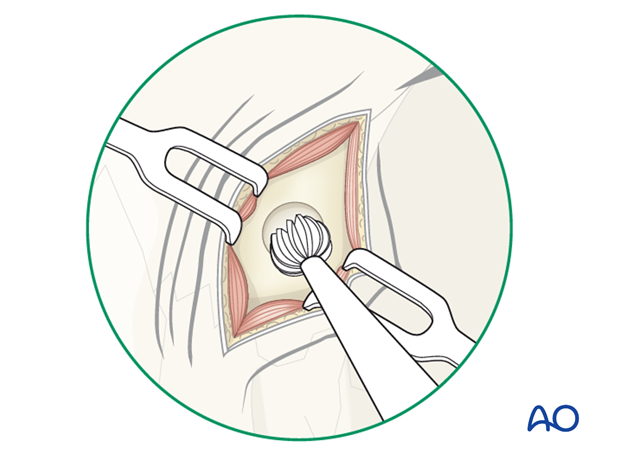

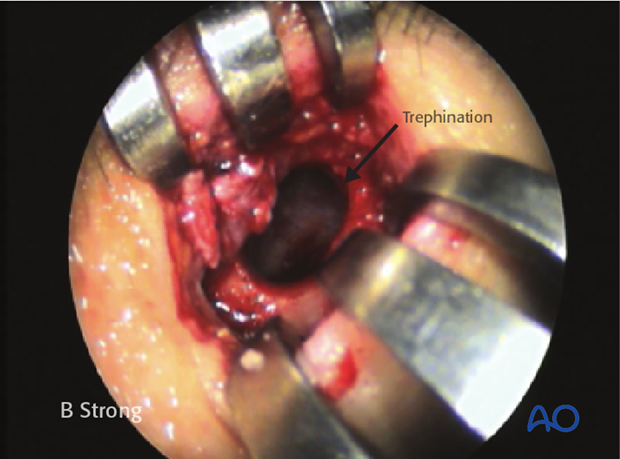

A 4 mm cutting burr is used to make a small frontal sinosotomy (trephination).

A suction is used to free the sinus of any blood or mucus.

The posterior table and frontal recess can then be assessed with a 0° and/or 30° endoscope for evidence of mucosal lacerations, hematomas, or CSF leaks.