Repair of periorbital soft-tissue injuries and lacrimal system in NOE injuries

1. Introduction

Patients who suffer orbital fractures frequently sustain equally severe injuries of the periorbital soft tissues, primarily the eyelids and lacrimal (drainage) system. Meticulous repair of the soft-tissue injuries is as important as accurately reconstructing the bony defect.

Avulsive injuries as seen in dog bites and high-energy trauma can provide unique challenges to the reconstructive surgeon.

2. Classification of eyelid lacerations

Introduction

When evaluating a patient with an eyelid laceration, there are two crucial determinations: first, whether it is a partial or full-thickness laceration, especially involving the lid margin, and second, whether the lacrimal canalicular system is damaged or transected by the injury.

Partial thickness

In this type of injury, the anterior lamellar structures of the eyelid (skin and orbicularis muscle) are damaged, but the laceration usually extends to involve areas of the eyelid margins. The key to managing this type of laceration is a precise realignment of the eyelid margin, to include skin, muscle, and tarsal plate so there is no discontinuity in the lashes or contour deformity of the lid margin.

Full thickness

A full-thickness laceration is defined as a complete disruption of the anterior and posterior lamellar structures of the eyelid.

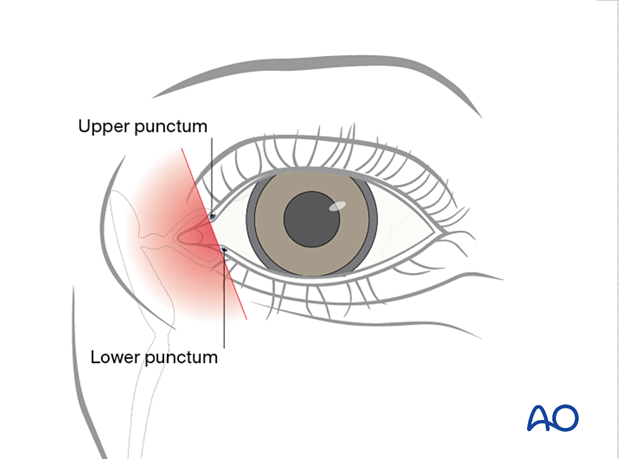

It is most important to determine if the canalicular system is involved. By definition, any laceration medial to the upper or lower punctae involves the canalicular system with rare exceptions. These injuries can be further subdivided into monocanalicular or bicanalicular injuries. Most monocanalicular injuries can be managed by techniques that intubate and stent that canaliculus. Bicanalicular lacerations will need a technique that places a stent through the entire system from the punctum to the nasolacrimal duct. Several commercial lacrimal intubation systems are available which provide the items necessary for a complete canalicular intubation from the punctum through the entire nasolacrimal duct, exiting in the nose. The technique we show can be applied utilizing any of these devices.

There can be more than one full-thickness laceration simultaneously in a single eyelid where one involves the canalicular system and the other does not.

Full-thickness (without canalicular involvement)

By definition, a full-thickness eyelid laceration without canalicular involvement is located lateral to the punctum.

Full thickness (with canalicular involvement)

Lacerations involving the canalicular system can damage one or both canaliculi. If both canaliculi are disrupted, a bicanalicular intubation is required for treatment. If only one of the two canaliculi is involved, only monocanalicular intubation may be sufficient for treatment. The circumstances where monocanalicular intubation may not be sufficient include high energy injuries or injuries with a significant avulsive component, such as dog bite injuries. If contusion injury and crushing of the non-divided canaliculus is presumed, intubation of both canaliculi is preferred to stent the non-divided canaliculus.

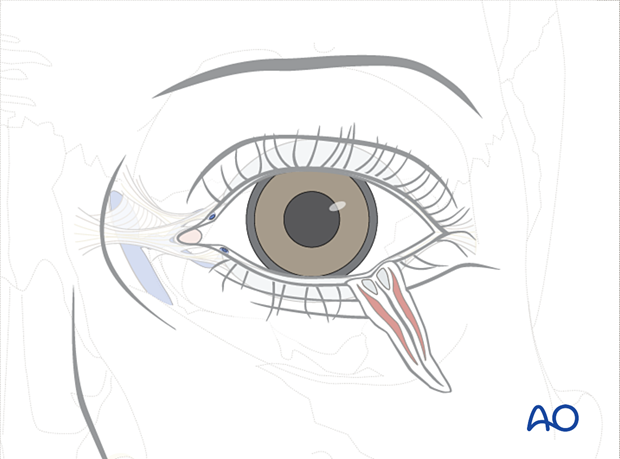

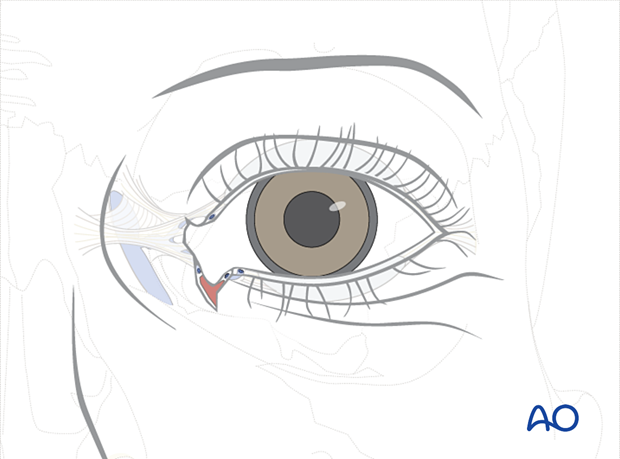

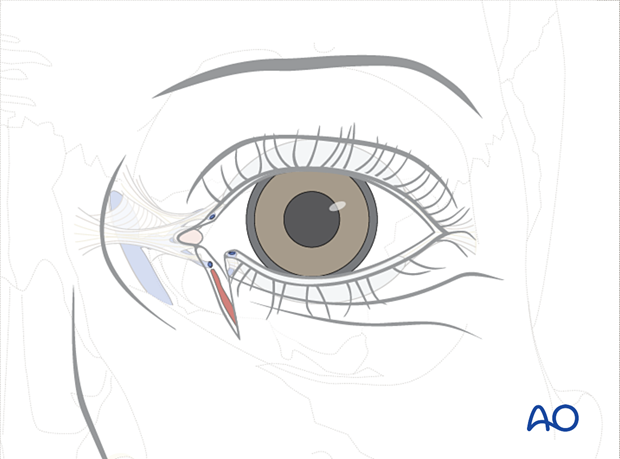

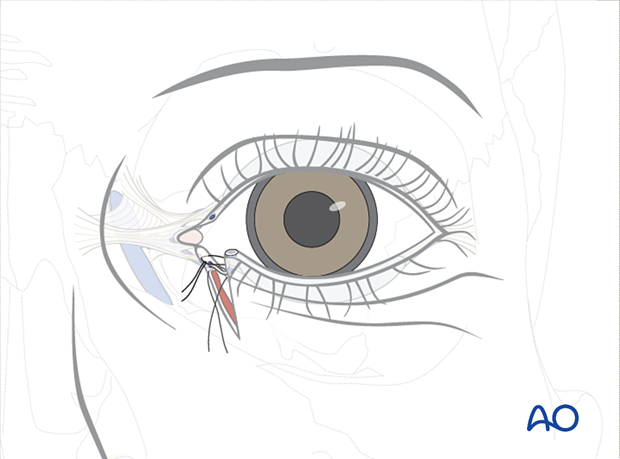

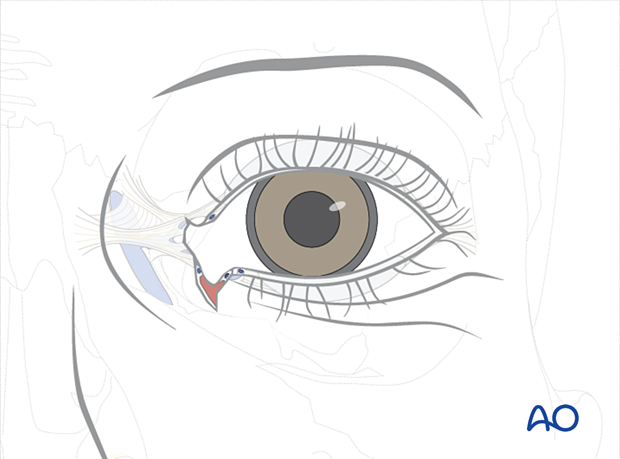

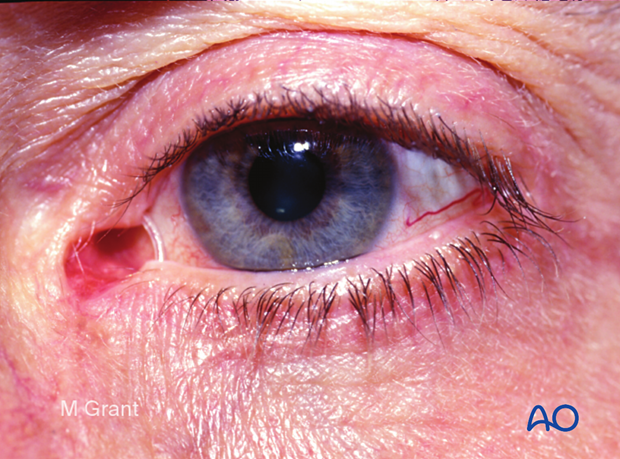

This illustration shows monocanalicular involvement.

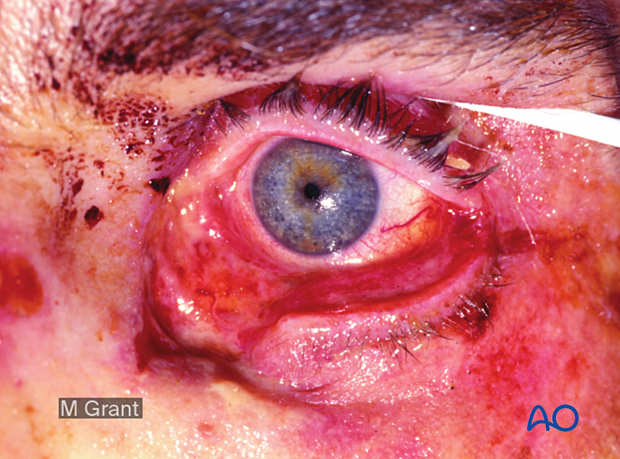

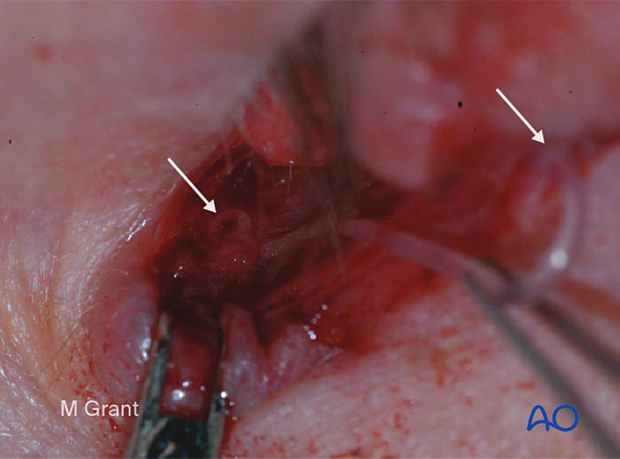

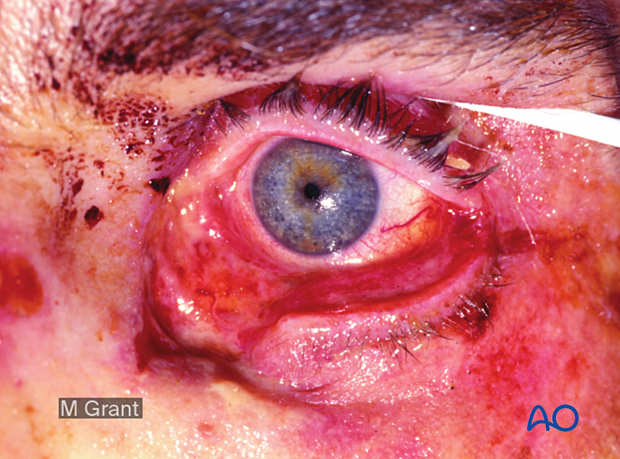

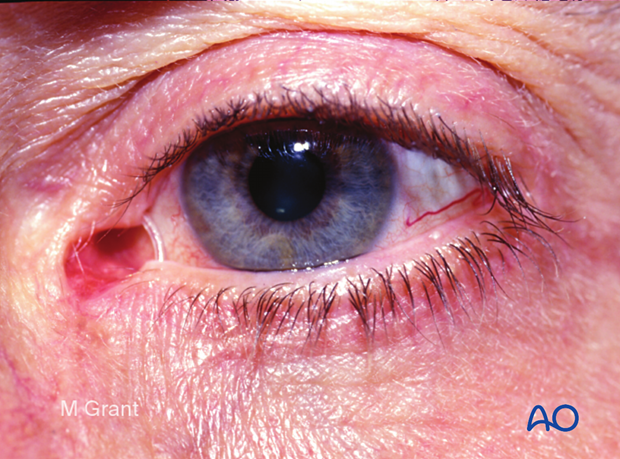

This clinical photograph illustrates inferior canalicular disruption with a significant avulsive soft-tissue injury to the lower eyelid and upper cheek. This is a typical example of a monocanalicular injury that may be best handled by bicanalicular intubation.

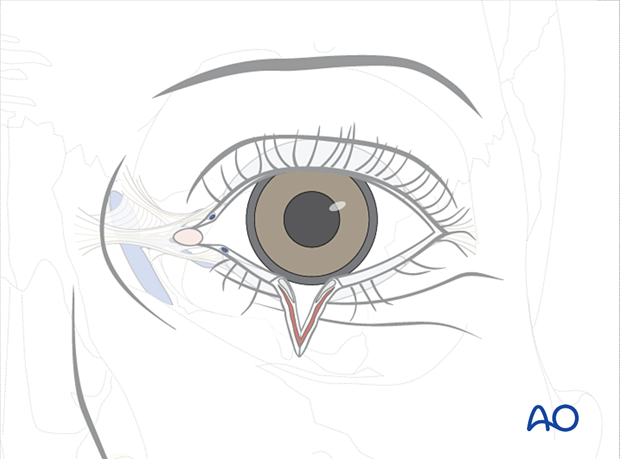

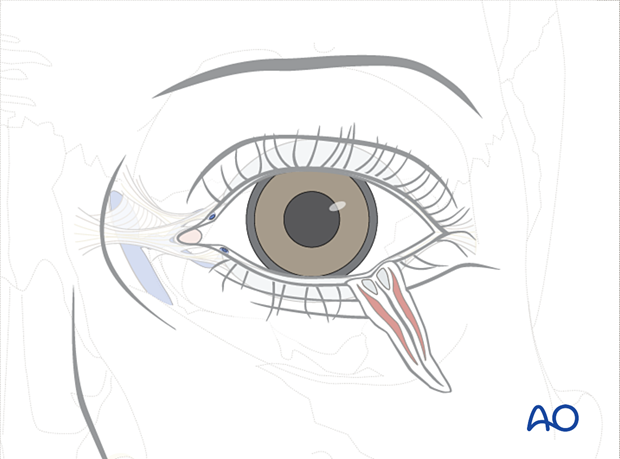

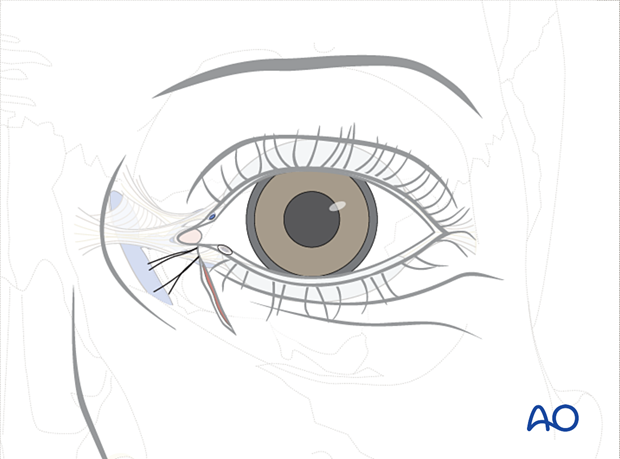

This illustration shows a bicanalicular involvement.

3. Repair: Partial thickness

In this type of injury, the anterior lamellar structures of the eyelid (skin and orbicularis muscle) are damaged, and the laceration extends to the eyelid margin. Accurate anatomic realignment of the margin is the most important principle in treating this injury. Before closure, the edges of the wound should be carefully debrided of any devitalized tissue or foreign material.

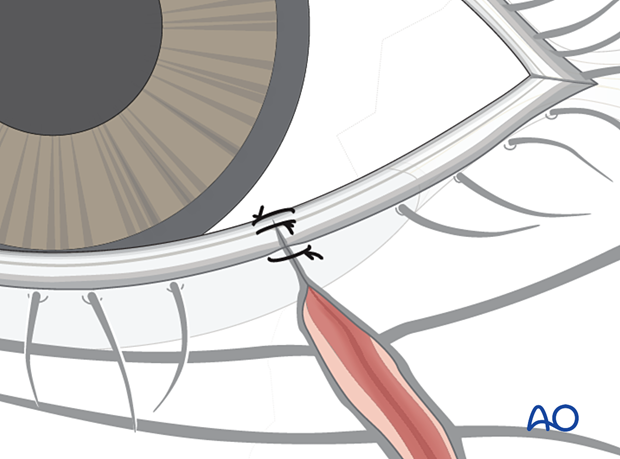

The eyelid margin is anatomically realigned, typically with two 8.0 sutures oriented perpendicular to the direction of the laceration. The sutures are placed such that one is anterior to the cilia, and one is posterior.

Some surgeons prefer three sutures at the lid margin:

- One in the mucosa margin

- One at the Gray line

- The third at the cilia

The skin is closed with multiple interrupted monofilament sutures. Deep closure of the soft tissue preliminarily aligns the skin with fine absorbable sutures in the deep layers of muscle, mucosa, and soft tissue.

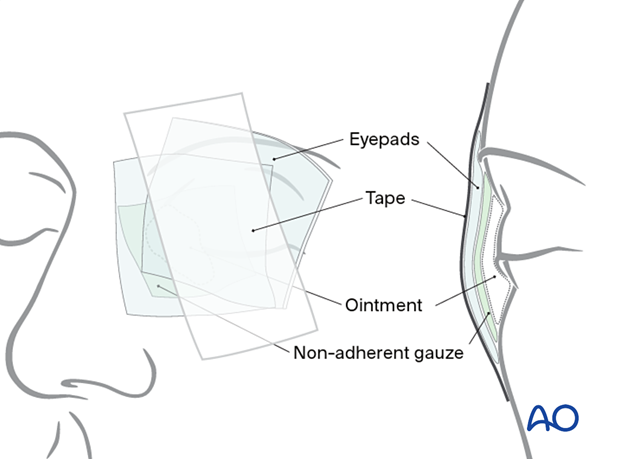

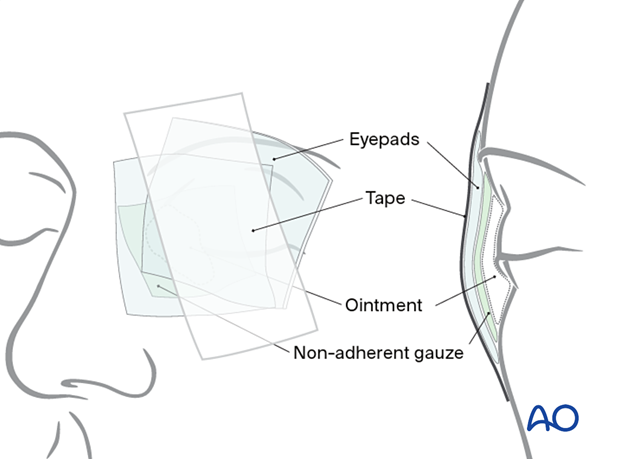

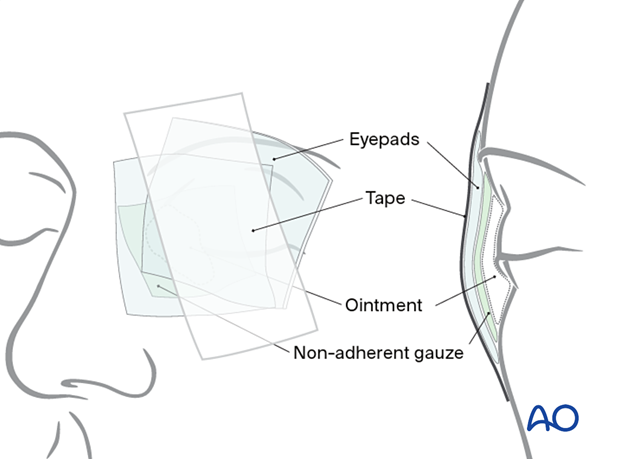

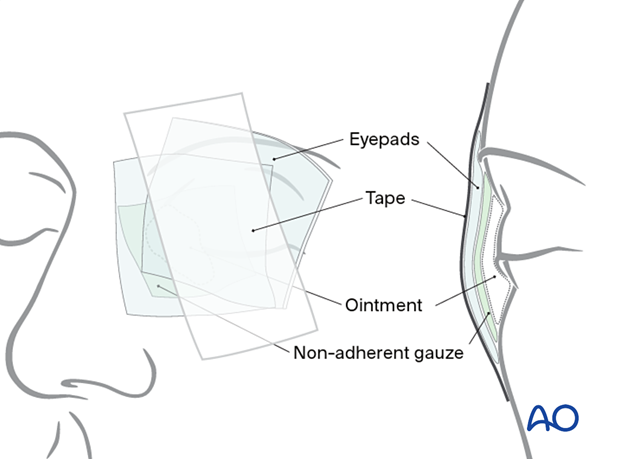

Aftercare

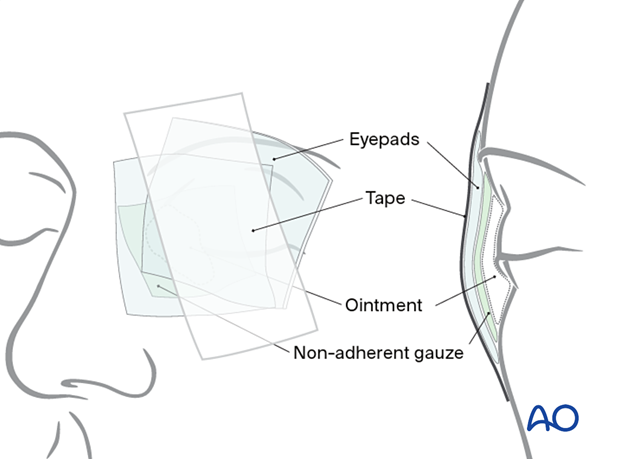

Typically, the wound is dressed with an ophthalmic ointment, which should be pH controlled relative to the needs of the surface of the eye. Some ointments contain a combination of steroids and antibiotics, and their use should be determined versus blend ointments such as Lacrilube®. The eye is patched shut for 24 hours with a non-adherent gauze pad, protected by a layer of ointment impregnated gauze such as Xeroform®. A Frost suture can be utilized for superior traction and taped above the brow to ensure eyelid closure. This suture can be placed through skin and muscle alone and need not go through the tarsal plate or lid margin as inadvertent disruption of either structure can occur with a cutting needle. Once the patch is removed, a bland or combined steroid/antibiotic ointment is prescribed for 10–14 days. These ointments are protective and are thick enough to blur vision. The patient must be warned of this effect. Alternatively, lubricating eye drops can be used to facilitate vision, but they provide less protection. Generally, cutaneous sutures are removed at postoperative day 7–14. Eyelid margin sutures are removed carefully at day 10–14, as healing is slow, depending on wound tension and soft-tissue edema.

4. Repair: Full-thickness (without canalicular involvement)

In contrast to a partial thickness laceration, both the anterior and posterior lamellar structures of the eyelid are violated in a full-thickness laceration. Anterior lamellar structure includes the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle. The posterior lamella includes the tarsal plate or orbital septum and the conjunctiva. Complete eyelid transections can be caused by sharp or blunt injuries. If these are avulsive or crushing forces, considerable shredding of soft tissue may occur.

Debridement of devitalized soft tissue should be completed; however judicious skill is required when doing so.

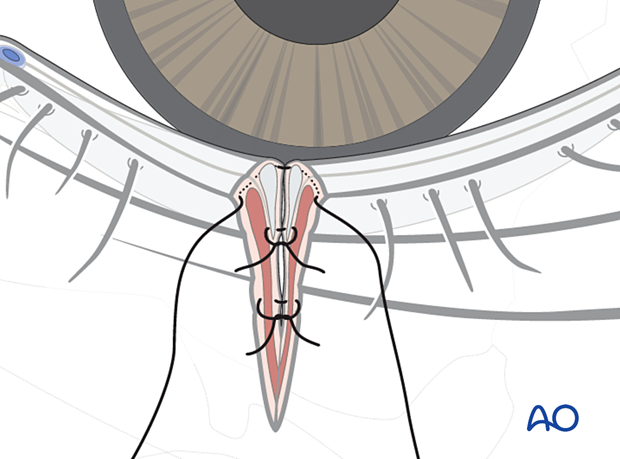

The initial step in treating these injuries is re-approximation of the conjunctiva followed by the tarsal plate. This is accomplished by placing two or three 6.0 slow-resorbing monofilament sutures through the tarsus with the knots tied anteriorly. The number of sutures placed will depend on the location and orientation of the laceration. For example, a central oblique laceration will require three or more sutures to stabilize the tarsal plate; but lacerations at the nasal or temporal aspect of the eyelid rarely need more than two.

Following stabilization of the tarsal plate, the surgeon should anatomically realign the several structures of the eyelid margin.

This is best accomplished with three 7.0 or 8.0 monofilament sutures oriented perpendicular to the direction of the laceration. Generally, two sutures are placed anterior to the cilia, and one is placed posteriorly. Three sutures are typically required to control the rotation of the margin due to the remaining tarsal instability.

Lastly, the skin edges are carefully debrided of any devitalized tissue. The skin and orbicularis are precisely closed with internal and external multiple interrupted monofilament sutures. Deep closure of the orbicularis muscle is accomplished, and closure of the orbital septum (if involved) must also be performed.

Aftercare

Typically, the wound is dressed with an ophthalmic ointment, which should be pH controlled relative to the needs of the surface of the eye. Some ointments contain a combination of steroids and antibiotics, and their use should be determined versus blend ointments such as Lacrilube®. The eye is patched shut for 24 hours with a non-adherent gauze pad, protected by a layer of ointment impregnated gauze such as Xeroform®. A Frost suture can be utilized for superior traction and taped above the brow to ensure eyelid closure. This suture can be placed through skin and muscle alone and need not go through the tarsal plate or lid margin as inadvertent disruption of either structure can occur with a cutting needle. Once the patch is removed, a bland or combined steroid/antibiotic ointment is prescribed for 10–14 days. These ointments are protective and are thick enough to blur vision. The patient must be warned of this effect. Alternatively, lubricating eye drops can be used to facilitate vision, but they provide less protection. Generally, cutaneous sutures are removed at postoperative day 7–14. Eyelid margin sutures are removed carefully at day 10–14, as healing is slow, depending on wound tension and soft-tissue edema.

5. Repair: Full-thickness (monocanalicular intubation)

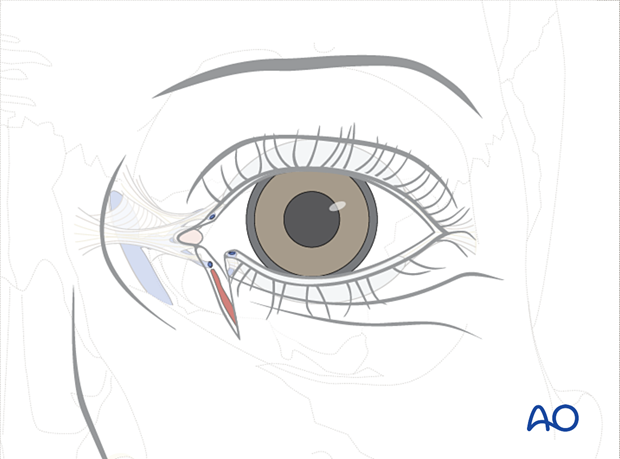

The punctum, proximal, and distal segments of the involved canaliculus should be identified. In simple monocanalicular injuries, it is reasonable to proceed with monocanalicular intubation alone.

By convention, the punctum is the most proximal point of the lacrimal drainage system, and the nasolacrimal duct is the most distal point.

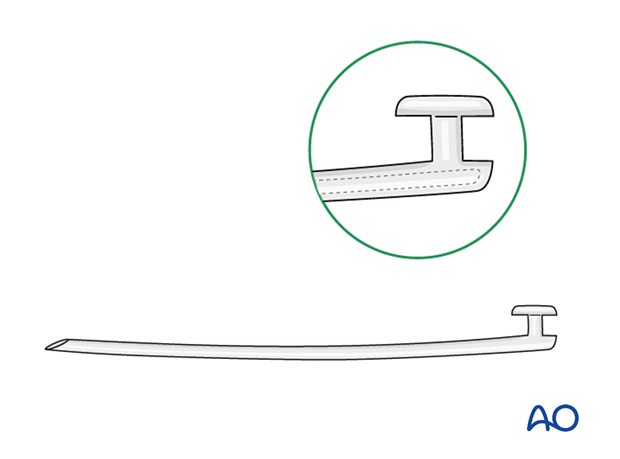

Monocanalicular intubation may utilize a specially designed stenting system, as illustrated. Alternatively, a bicanulicular stenting system can be modified for unilateral use and taped or sutured to the skin of the eyelid or nose.

While the stent is in place (typically 4–6 weeks), the canaliculus may be partially or completely blocked. During this period, patients may note excessive tearing (epiphora).

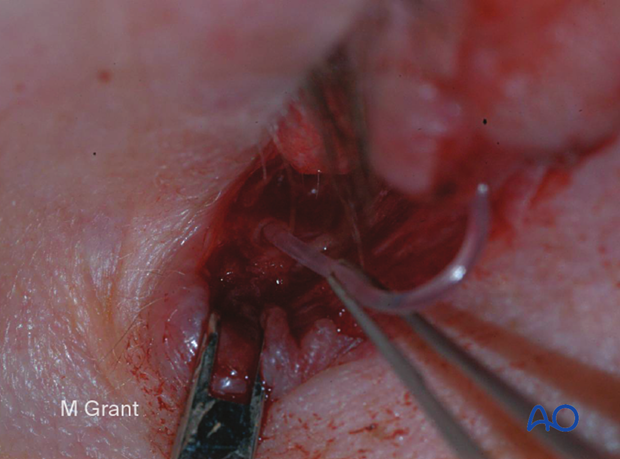

This clinical photograph shows the distal segment of the inferior canaliculus within the laceration. This can often be difficult to identify but typically looks like a white/opaque structure highlighted by the darker background.

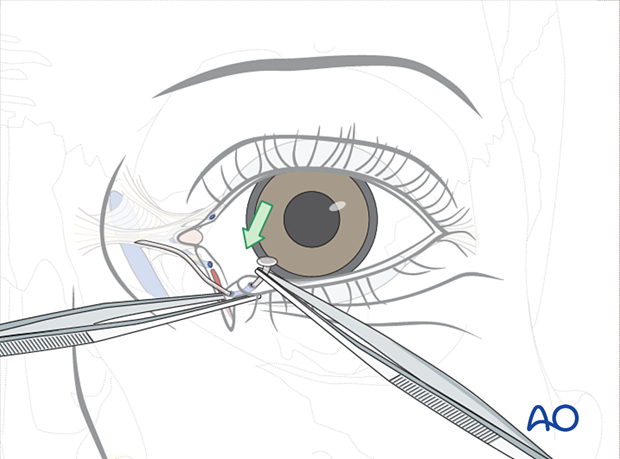

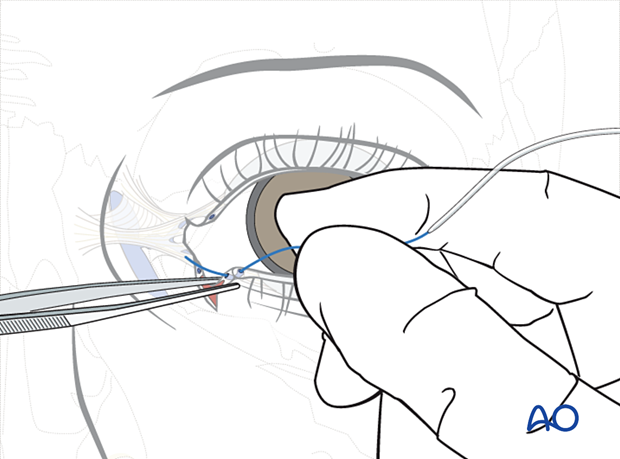

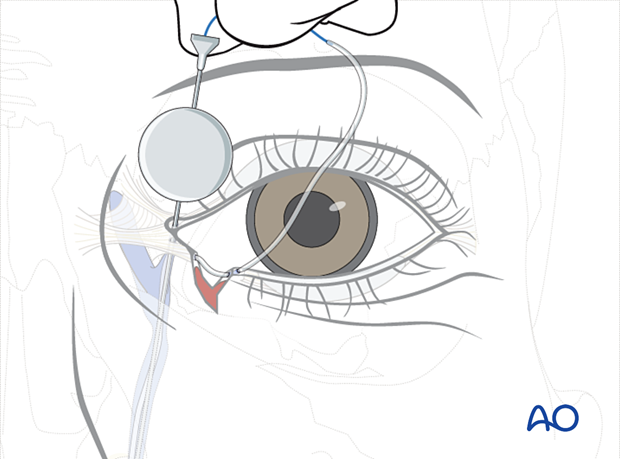

A monocanalicular stent is threaded through the punctum and externalized through the proximal lacerated segment of the involved canaliculus.

The proximal segment is identified, and the stent is placed into the proximal segment.

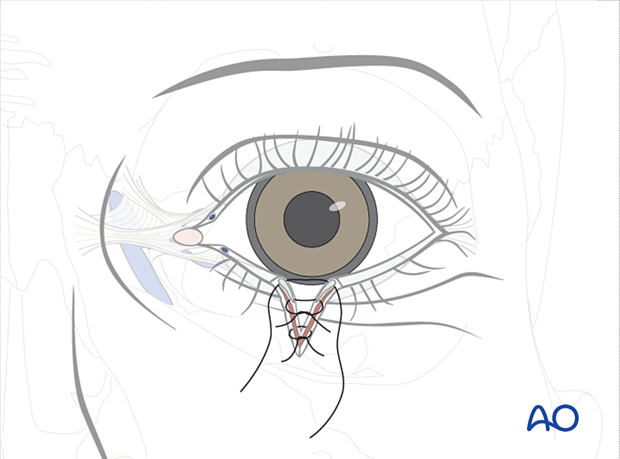

Two 6.0 monofilament sutures are placed but not tied, one superior to the canaliculus and one inferior. The canaliculus may be individually approximated with absorbable sutures under magnification.

The inferior suture is tied first, followed by the superior suture. This will reconstruct the canaliculus and reapproximate the eyelid. One or more lid margin sutures may be required as necessary to realign the lid margin.

The skin is closed with multiple interrupted sutures.

Aftercare

Typically, the wound is dressed with an ophthalmic ointment, which should be pH controlled relative to the needs of the surface of the eye. Some ointments contain a combination of steroids and antibiotics, and their use should be determined versus blend ointments such as Lacrilube®. The eye is patched shut for 24 hours with a non-adherent gauze pad, protected by a layer of ointment impregnated gauze such as Xeroform®. A Frost suture can be utilized for superior traction and taped above the brow to ensure eyelid closure. This suture can be placed through skin and muscle alone and need not go through the tarsal plate or lid margin as inadvertent disruption of either structure can occur with a cutting needle. Once the patch is removed, a bland or combined steroid/antibiotic ointment is prescribed for 10–14 days. These ointments are protective and are thick enough to blur vision. The patient must be warned of this effect. Alternatively, lubricating eye drops can be used to facilitate vision, but they provide less protection. Generally, cutaneous sutures are removed at postoperative day 7–14. Eyelid margin sutures are removed carefully at day 10–14, as healing is slow, depending on wound tension and soft-tissue edema.

This clinical photograph shows the patient after suture removal at ten days. The patient will return 4–6 weeks following the repair for removal of the stent.

6. Repair: Full-thickness (bicanalicular intubation)

In more severe eyelid trauma, including most avulsive monocanalicular injuries and all bicanalicular injuries, bicanalicular intubation is required. Below, we illustrate a technique that can be utilized with either type of injury using any of the commercial systems currently available.

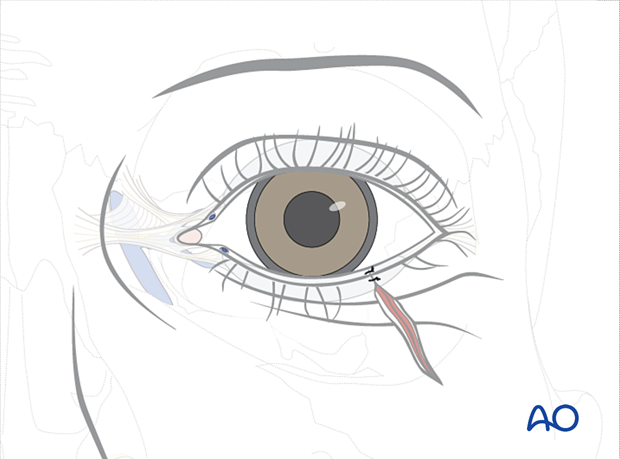

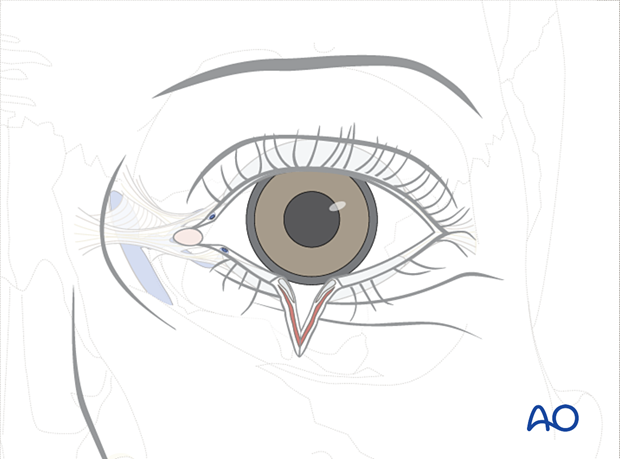

In this example, the patient has sustained an inferior canalicular laceration with significant soft-tissue damage. This type of injury will require bicanalicular intubation to stent both lacrimal canaliculi to achieve optimal results.

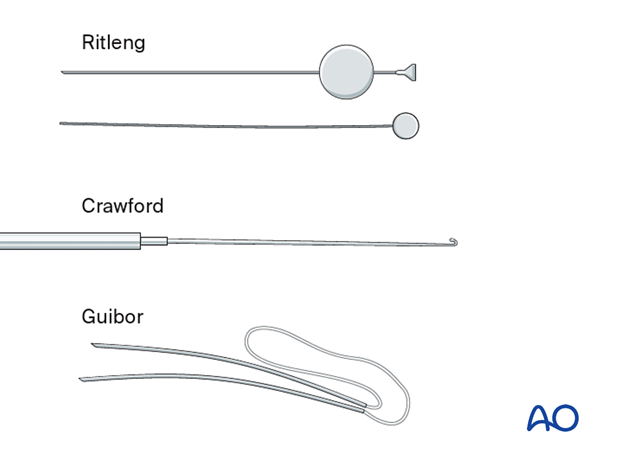

Several commercial systems exist, including the Ritleng, Crawford, Guibor, and Jones.

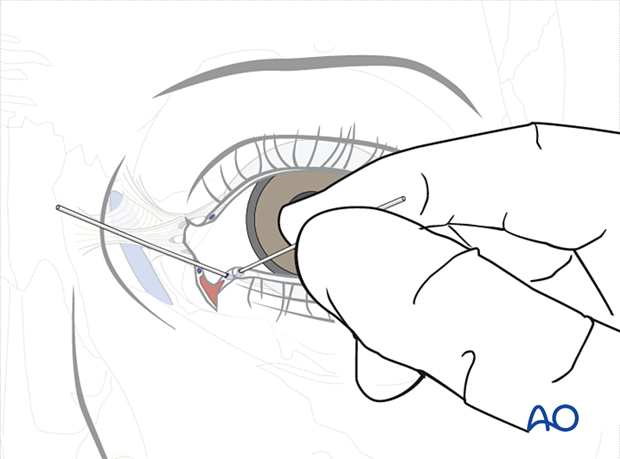

Every canalicular intubation requires precise identification of the punctum and the proximal and distal ends of the involved canaliculus. It is usually advisable to dilate the lacrimal punctum with a lacrimal dilator prior to instrumentation of the canaliculus. The surgeon can then proceed with the intubation of the system and the repair. We will utilize the Ritleng system in this example, but the general technique is applicable for all.

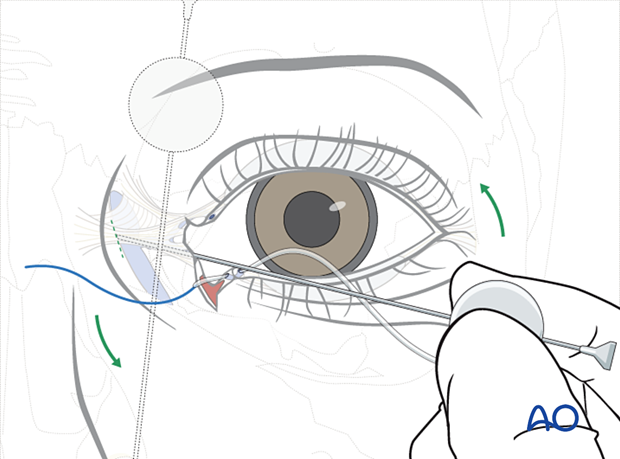

First, the lacrimal punctum is dilated, and the stent is then passed through the punctum and externalized through the proximal segment within the laceration.

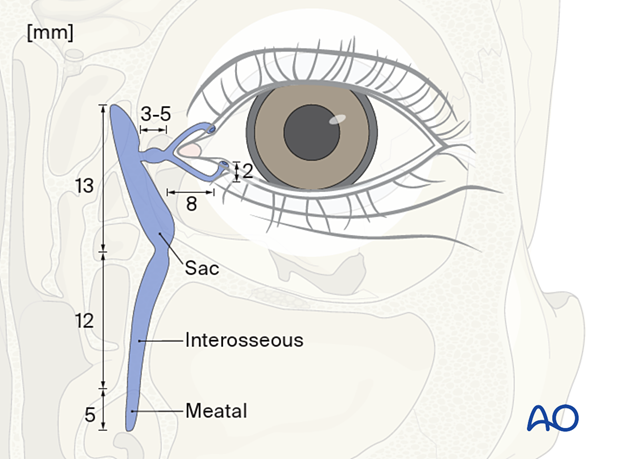

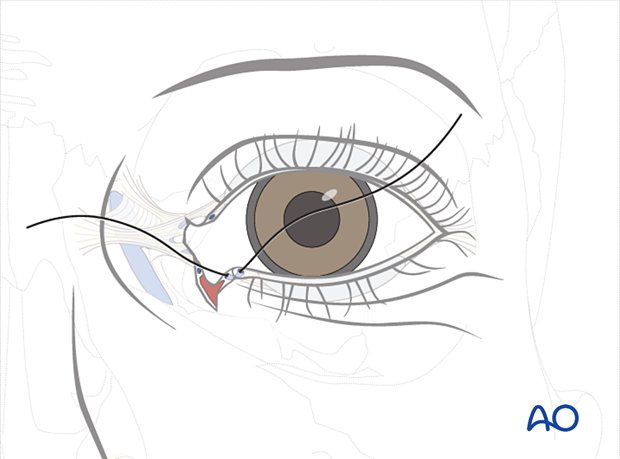

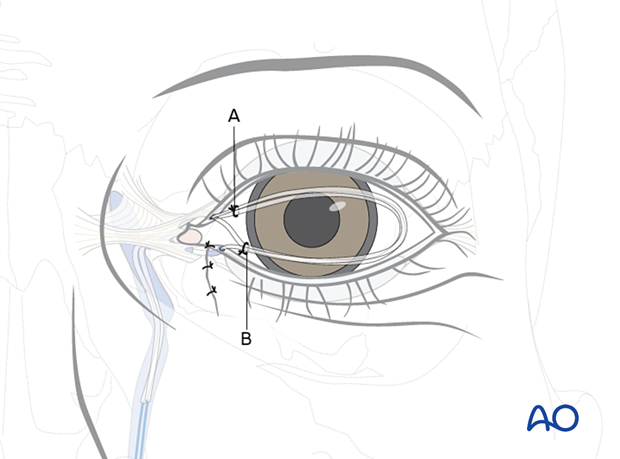

This illustration shows the anatomic shape of the lacrimal drainage system.

Note that there is a vertical segment in each canaliculus before the more horizontal component that goes to the common canaliculus. The direction of the nasolacrimal duct then proceeds inferiorly to descend into the nasal cavity where it exits beneath the inferior turbinate.

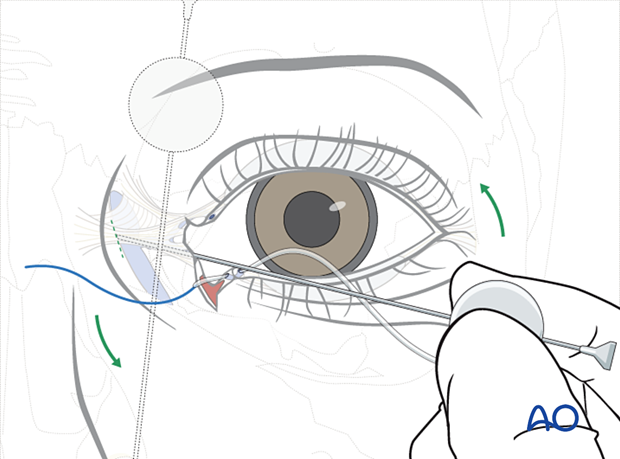

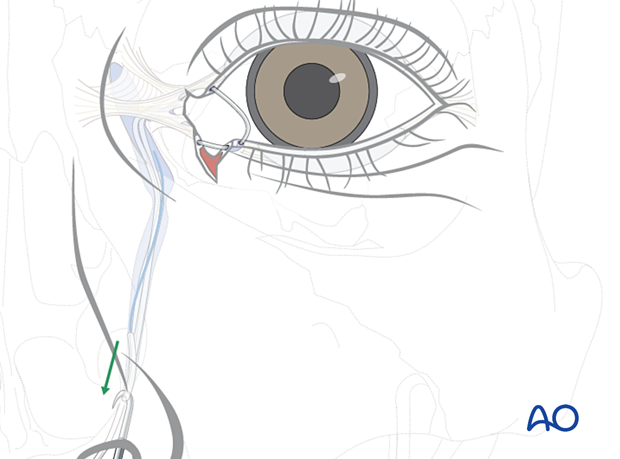

Next, the Ritleng introducer with the stylette in place is passed through the distal segment of the lacrimal duct laceration. The initial passage is advanced parallel to the eyelid through the common canaliculus and into the nasolacrimal duct. A hard stop is encountered and the tip of the Ritleng introducer is turned vertically in the lacrimal sac. This maneuver rotates the Ritleng introducer to a posture 90°superiorly so that it is now oriented perpendicular to the plane of the eyelid and can be advanced through the nasal lacrimal duct and into the nose.

After the stylette is visualized below the inferior turbinate, it is grasped, and the tube is advanced through the nasolacrimal duct. The stylette is now removed. Using a Ritleng hook, a "grooved director", or a hemostat, the stylette is grasped and the stent may be tied and taped to the cheek, exiting from one nostril. This allows for future retrieval from the nose.

If the upper canaliculus is also lacerated (ie, in an injury with bicanalicular involvement), it can be intubated as described for the lower canalicular intubation.

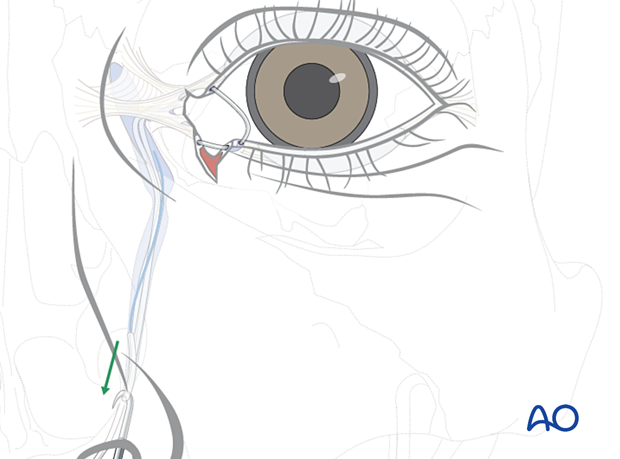

If, as in the illustrated case, the upper canalicular system is intact, then the Ritleng introducer with the stylette in place is advanced through the punctum, the upper canaliculus, and the common canaliculus until a hard stop is encountered. Then, the surgeon’s hand rotates the introducer 90°superiorly, and the Ritleng introducer is advanced through the nasolacrimal duct into the nose.

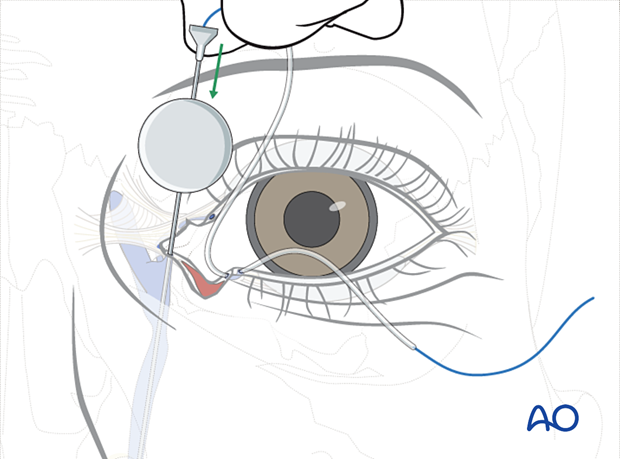

The stylette can be retrieved in the nose. The stent is then retrieved from the nose with a blunt-tipped hook, a grooved director, or a clamp. The stylette is then removed and the tubes tied with a silk suture which can be taped to the cheek adjacent to the nostril.

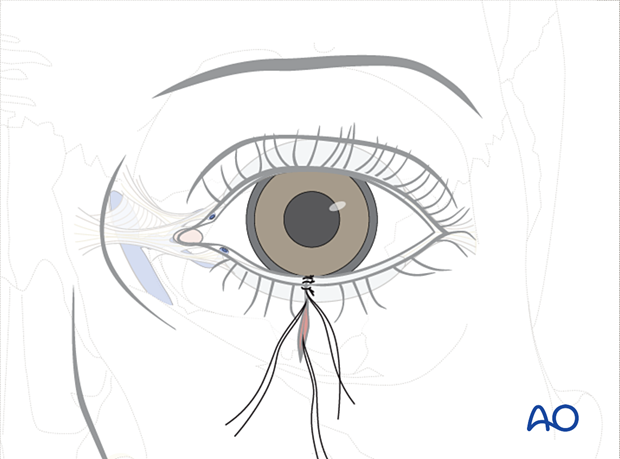

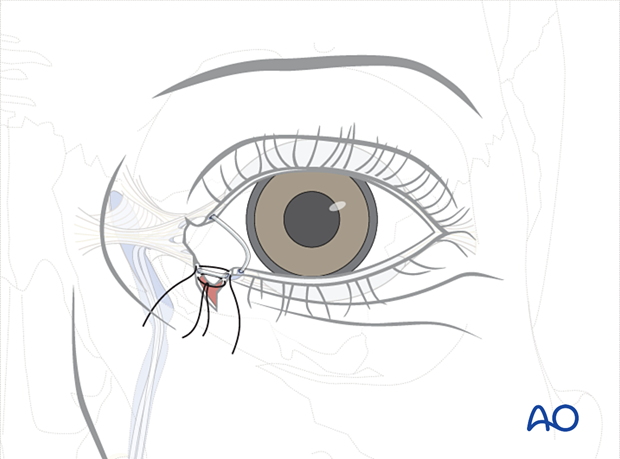

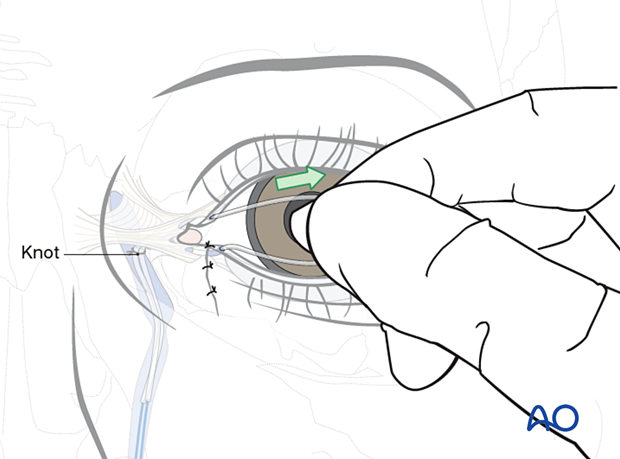

The laceration is closed in layers as previously described.

The inferior suture is tied first, followed by the superior suture. This will reconstruct the canaliculus and reapproximate the eyelid. One or more lid margin sutures may be required as necessary to realign the lid margin.

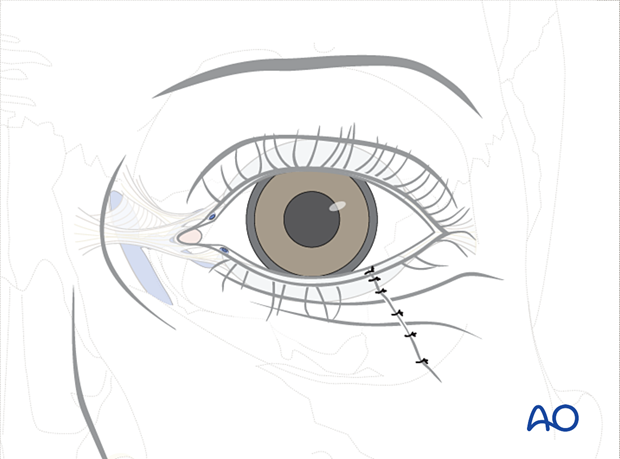

The skin is closed with multiple interrupted monofilament sutures.

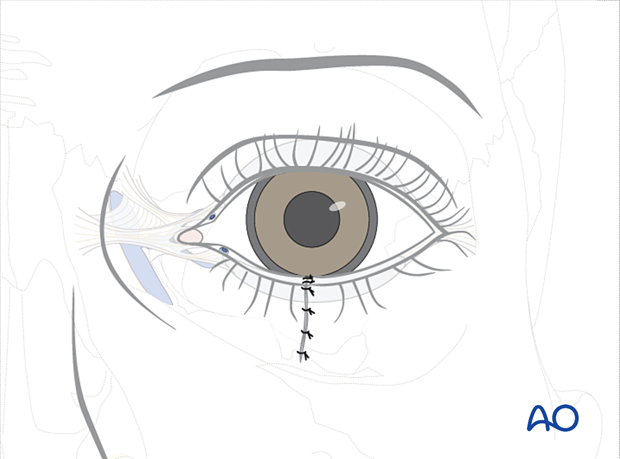

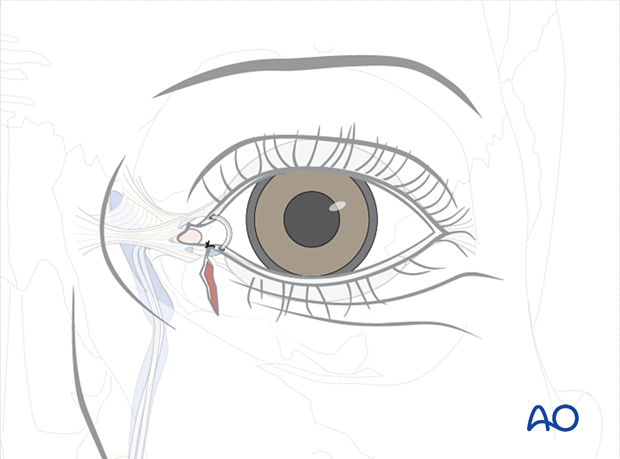

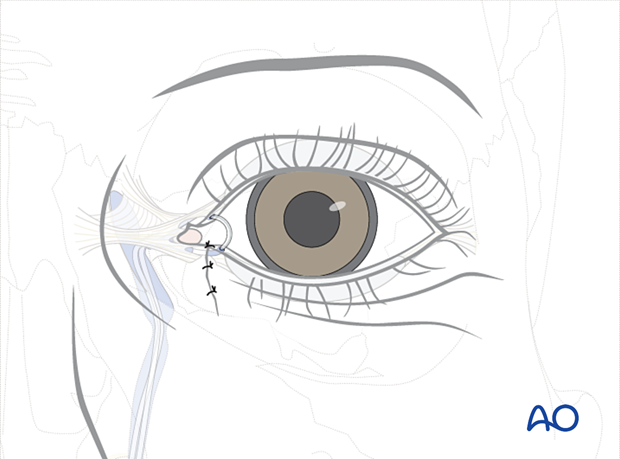

The final part of this procedure is adjusting the tension on the silicone stents. A 6.0 monofilament suture or a silk suture is tied around the silicone tubes at the level of the nostril.

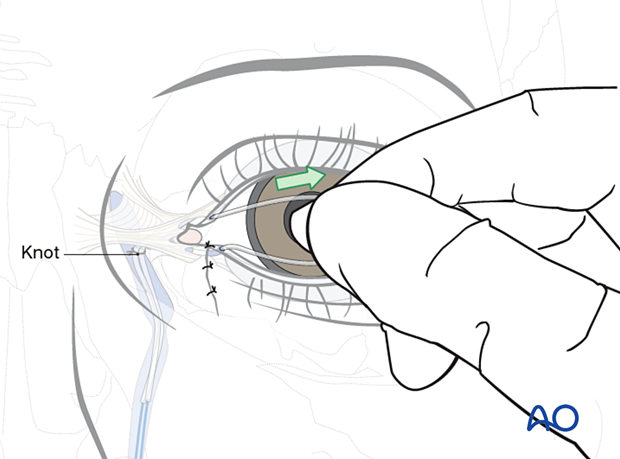

The knot is pulled through the upper canaliculus until a gentle loop is seen at the medial margin of the eyelids. This loop should not exert traction on the lacrimal punctum as it can damage the punctum by extending the laceration due to excess pressure.

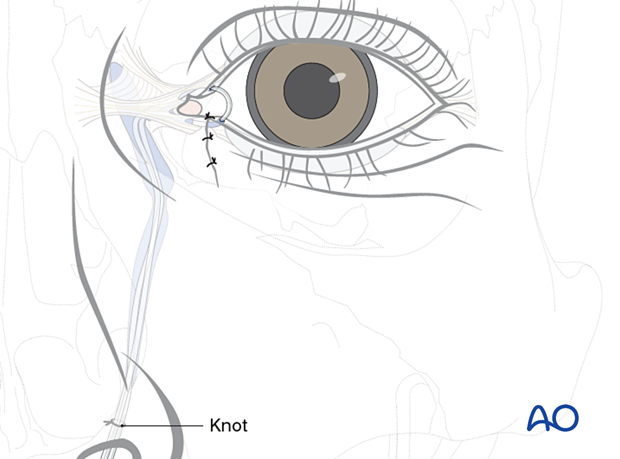

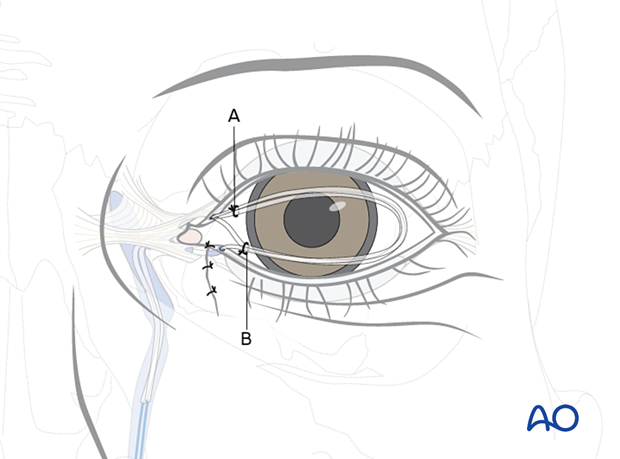

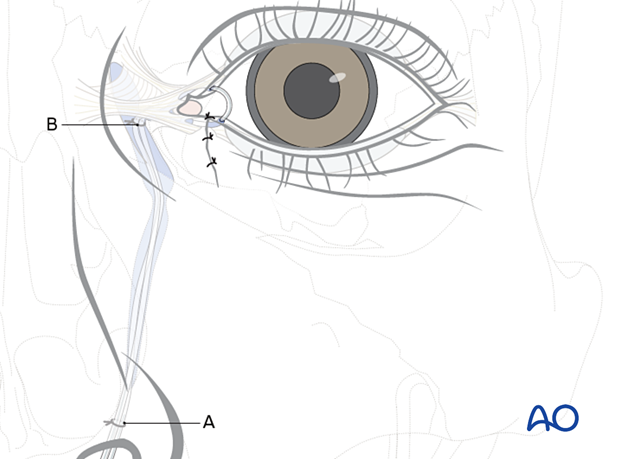

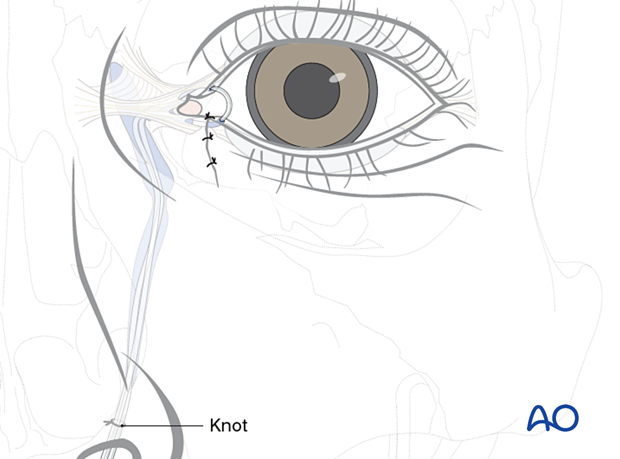

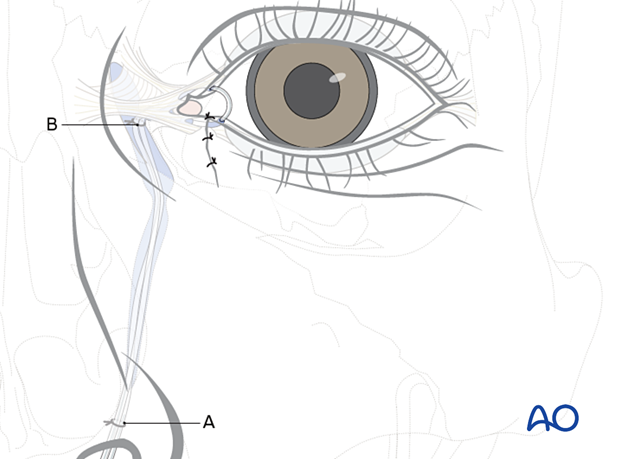

A second knot (B) is tied proximal to the first (A), corresponding to the level of the lacrimal sac. This is typically approximately 1.5 cm above the position at which the tubes emerge from the lower and upper punctae.

The second knot (B) is positioned in the lacrimal sac by pulling the two ends of the stent back through the nose so that the first knot is again placed at the nostril level.

The stents are cut just above the lower knot (A).

Aftercare

Typically, the wound is dressed with an ophthalmic ointment, which should be pH controlled relative to the needs of the surface of the eye. Some ointments contain a combination of steroids and antibiotics, and their use should be determined versus blend ointments such as Lacrilube®. The eye is patched shut for 24 hours with a non-adherent gauze pad, protected by a layer of ointment impregnated gauze such as Xeroform®. A Frost suture can be utilized for superior traction and taped above the brow to ensure eyelid closure. This suture can be placed through skin and muscle alone and need not go through the tarsal plate or lid margin as inadvertent disruption of either structure can occur with a cutting needle. Once the patch is removed, a bland or combined steroid/antibiotic ointment is prescribed for 10–14 days. These ointments are protective and are thick enough to blur vision. The patient must be warned of this effect. Alternatively, lubricating eye drops can be used to facilitate vision, but they provide less protection. Generally, cutaneous sutures are removed at postoperative day 7–14. Eyelid margin sutures are removed carefully at day 10–14, as healing is slow, depending on wound tension and soft-tissue edema.

The bicanalicular stents are left in place for approximately three months. At this point, the stent is removed by cutting the loop between the upper and lower punctum and pulling the stent out through the nostril.

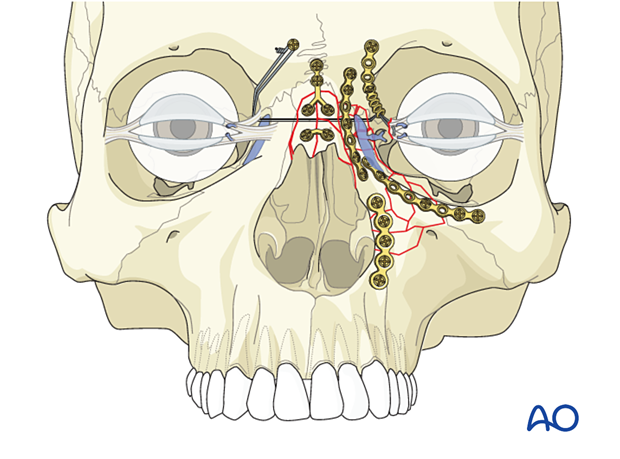

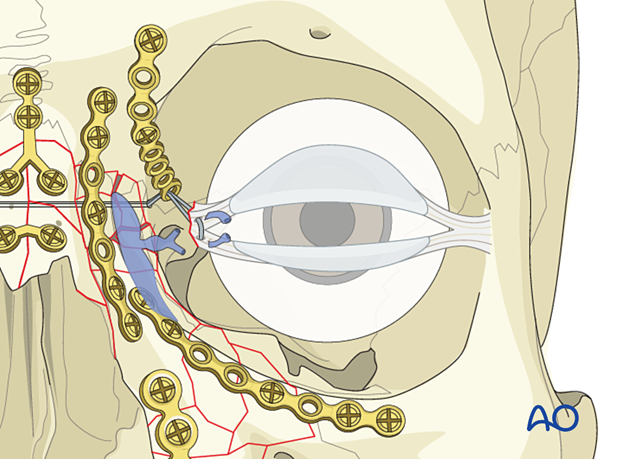

7. Involvement of the lacrimal system in NOE fractures

As in any injury involving multiple structures, appropriate repair sequencing is important. If the surgeon is faced with an NOE fracture with evident lacrimal disruption, reducing the fracture and stabilizing the craniofacial skeleton should precede any attempt to reconstruct the lacrimal system.

Typically, even in comminuted NOE fractures, the medial canthal-bearing fragment is large enough not to disrupt the eyelids and lacrimal system. It is only in high-energy injuries, or injuries with a significant sharp or avulsive component, that the lacrimal system is directly injured by an additional lid laceration.

These patients will have a soft-tissue skin defect or laceration medial to the upper or lower puncta. Patients may exhibit fractures along the path of the nasolacrimal duct.

If transected, the lacrimal canaliculi should be repaired and intubated with a stent.

It has not been shown to be beneficial to try to intubate the nasolacrimal duct at the time of fracture repair in the absence of canalicular lacerations. No particular intervention is routinely required for the nasolacrimal duct other than anatomic repair of the bony fragments. Dacryocystorhinostomy can be completed secondarily in cases with refractory nasal lacrimal duct obstruction.

Below we will outline a method of treating lacrimal system injury in patients with an NOE fracture.

In NOE fractures with a damaged lacrimal system, repositioning the medial canthal-bearing fragment is the first step to execute. This will almost certainly require stabilization with some form of transnasal wiring.

Once this has been accomplished, reconstruction of the lacrimal system can be performed.

The proximal portion of the lacrimal system, the inferior and the superior canaliculi, are identified by placing lacrimal probes within the lumen.

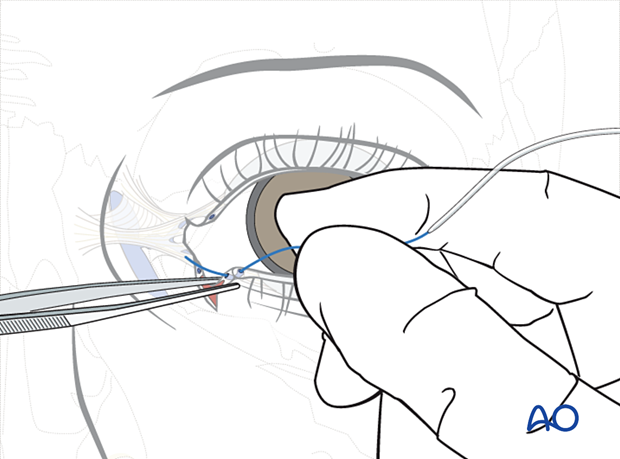

The distal segments of the affected canaliculi are identified within the laceration. 6.0 monofilament sutures are placed but not tied superior and inferior to the affected canaliculi.

The probes are removed.

First, the stent is passed through the punctum and externalized through the proximal segment within the laceration.

Next, the Ritleng introducer with the stylette in place is passed into the distal segment of the laceration and advanced parallel to the eyelid through the common canaliculus (parallel to the eyelid) until a hard stop is encountered. At this point, the tip of the Ritleng introducer is in the lacrimal sac. Next, the surgeon rotates the Ritleng introducer 90°superiorly, so that it is now perpendicular to the plane of the eyelid, and advances the introducer down the nasal lacrimal duct.

The stylette is removed, and the Ritleng stent is advanced through the Ritleng introducer into the nose. Using a Ritleng hook, the stent is retrieved in the nose.

The sutures are tightened, and once the appropriate tension has been achieved, the knots are tied and the sutures trimmed. Any residual skin defect should be closed with interrupted sutures.

The final part of this procedure is adjusting the tension on the silicone stents. To do this, a 6.0 monofilament suture is tied around the silicone tubes at the nostril level.

The knot is then pulled through the upper canaliculus by gentle traction on the silicone tube.

A second knot (B) is tied proximal to the first (A), corresponding to the level of the lacrimal sac. This is typically approximately 1.5 cm above the position at which the tubes emerge from the lower and upper punctae.

The second knot (B) is positioned in the lacrimal sac by pulling the two ends of the stent back through the nose so that the first knot is again placed at the nostril level.

The stents are cut just above the lower knot (A).

Aftercare

Typically, the wound is dressed with an ointment containing a combination of steroids and antibiotics. The eye is patched shut with a non-adherent gauze pad for 24 hours. Once the patch is removed, a combined steroid antibiotic containing eye drops is prescribed for 10–14 days. Generally, cutaneous sutures are removed at postoperative day 7–10, eyelid margin sutures are removed at day 10–14, depending on wound tension and soft-tissue edema.

The bicanalicular stents are left in place for approximately three months. At this point, the stent is removed by cutting the loop between the upper and lower punctum and pulling the stent out through the nostril.

8. Case example: eyelid repair

A 22-year-old female suffered a MVA with multiple lacerations, avulsion, crushing and soft-tissue injury of the left cheek, and upper and lower eyelids.

Some margins of the soft tissue injury were refreshed.

Postoperative clinical picture.

Note that the left lower eyelid has a slight hump in the central area (gentle massaging of the left lower lid area was advised to the patient).

Late postoperative clinical picture.

Note that the lower eyelid hump has been improved.

9. Case example: lower eyelid repair

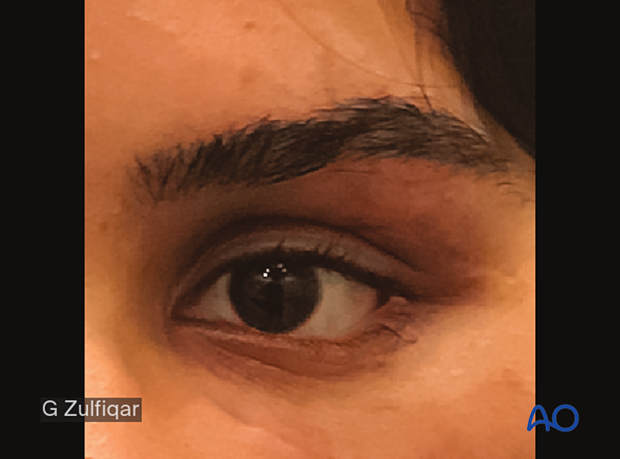

27-year-old male suffered an MVA. Note the disrupted left lower eyelid and the tarsal plate laceration.

Soft-tissue loss is present in the left infraorbital region.

Immediate postoperative clinical picture.

Late postoperative clinical picture.