Examination of patients with midfacial injuries

1. Introduction

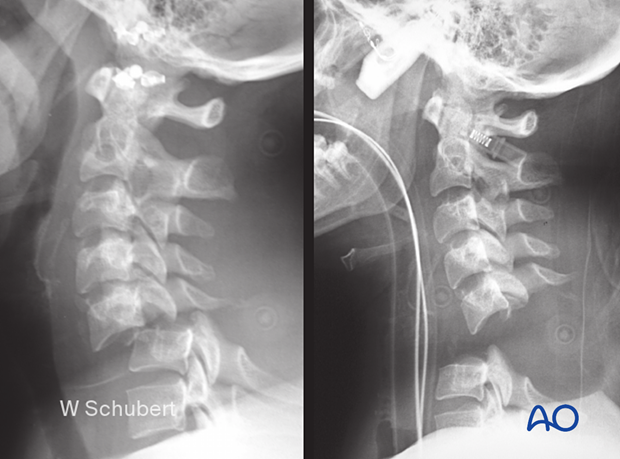

Airway and circulation should have the highest priority. This is followed by an assessment of the patient's neurological, visual, and cervical spine status.

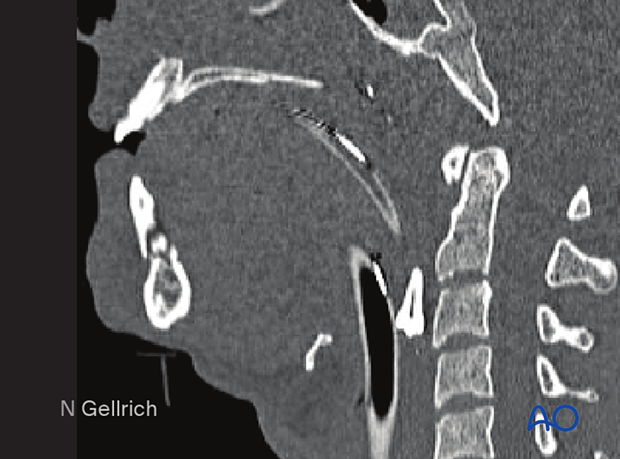

If possible, the patient's medical history should be considered to assess the individual fracture pattern in midfacial fractures. It could reveal preexisting occlusal deformities, nasal,paranasal sinuses, or ophthalmologic pathologies independent of the injury. Often midface fracture patients are admitted to the hospital unconscious and intubated. Particular regard has to be given to foreign bodies obstructing the airway, such as dislocated partial or full dentures or teeth fragments (see x-ray).

Furthermore, hard-tissue considerations, severe bleeding, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage may accompany and aggravate the treatment outcome.

Basic assessment of visual acuity is mandatory in the conscious patient. In the unconscious patient, regular light reflex testing should be performed. The swinging flashlight test should be included to give evidence on optic nerve function (relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)).

2. General considerations

A standard examination protocol is strongly recommended to clinically evaluate possible midfacial injuries, including a full examination of the head, eyes, ears, nose, throat, and neck.

For the experienced surgeon, assessment of midfacial injuries does not take very long.

A standard protocol is presented, which may vary according to regional differences and preferences.

The protocol presented here is regarded as mainly fracture or trauma oriented. It does not replace specialists' examinations (ie, ophthalmologist, neurosurgeon, otorhinolaryngologist, etc).

3. Signs and symptoms of midfacial fractures

Possible clinical signs for midfacial fractures include facial swelling (edema, hematoma, emphysema) (see picture), and deformity.

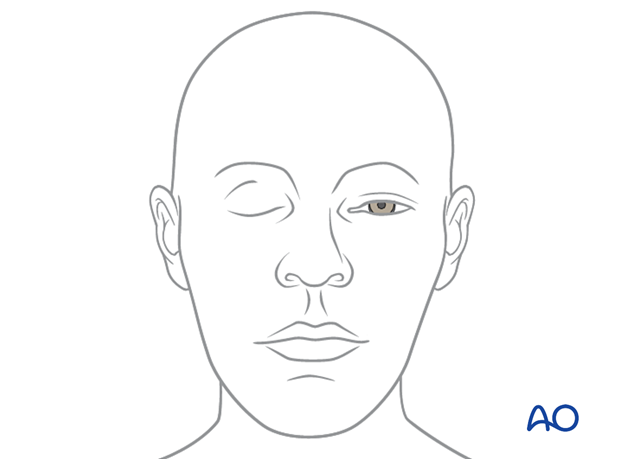

This patient has a bilateral peri-orbital hematoma indicating bilateral orbital fractures.

Other clinical signs for midfacial fractures include the following:

- Subconjunctival bleeding (hyposphagma) (see picture)

- Oronasal bleeding

- Palpable and crepitating dislocated bony contour in the periorbital region

- Displacement of the globe (hyper-, hypo-, eno-, exophthalmos)

- Displacement of the medial canthal tendon (depending on the degree of NOE fracture)

- Compromised ocular motility

- Double vision

- Sensory deficit (hypoesthesia, anesthesia, paresthesia) of the trigeminal nerve

- Localized pain

- Occlusal disturbance

- CSF leakage (in case of an anterior skull base or temporoparietal involvement)

4. Instruments for clinical examination

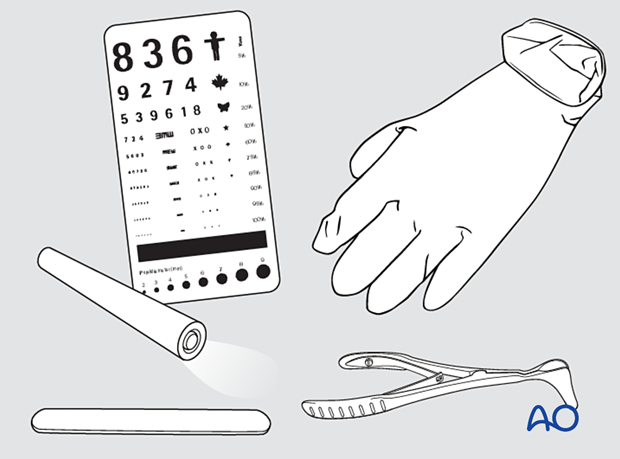

For clinical examination of midfacial fractures, the following instruments are recommended:

- Examination gloves

- Single-use tongue blades

- Examination light

- Visual chart

- Nasal speculum (in case of need for nasal examination)

5. Eye examination

Every patient with orbital fractures should have an ophthalmological evaluation that includes gross visual acuity testing, visual field testing, ocular motility, binocular vision, globe position, pupillary reaction, intraocular pressure testing.

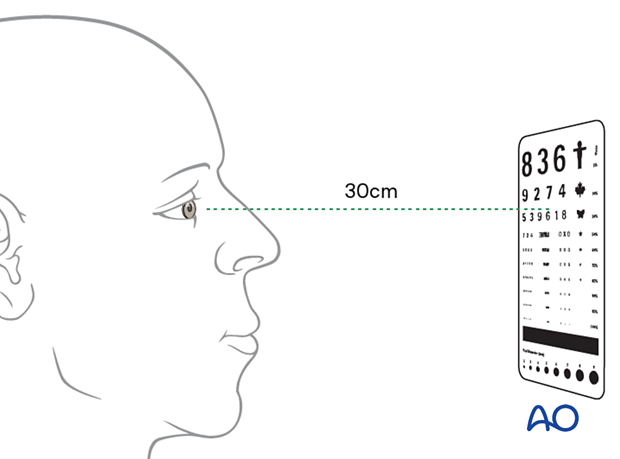

Acuity testing

The illustration shows visual acuity testing.

The illustration shows the Snell test.

Visual field testing

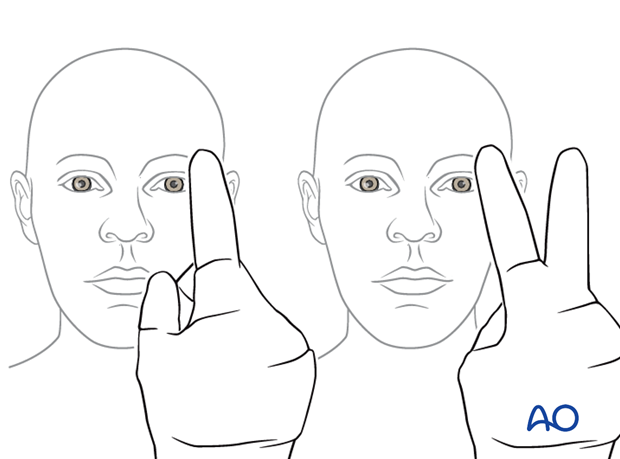

The illustration shows visual field tests.

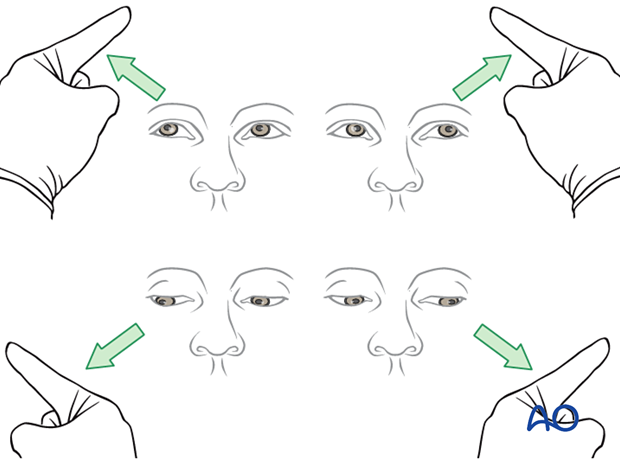

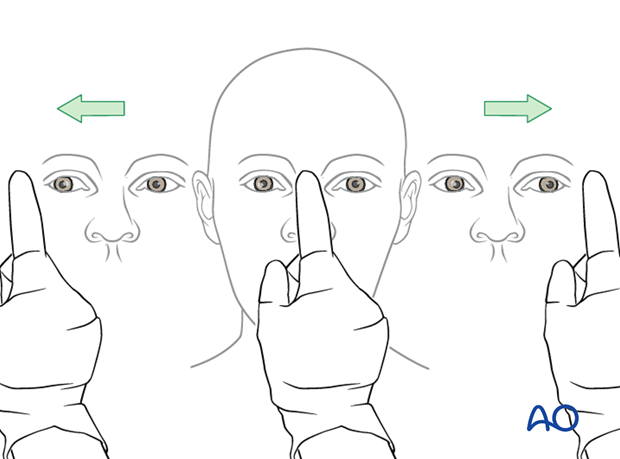

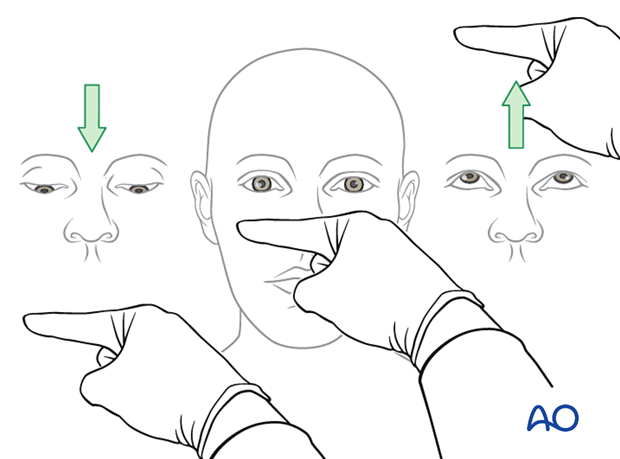

Testing of ocular motility

The illustration shows ocular motility testing.

Examine the patient to check that the extraocular muscles (EOM) are functioning properly.

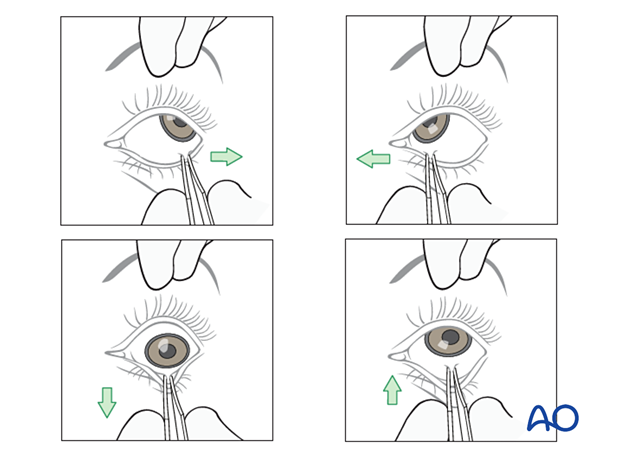

If the extraocular muscles (EOM) are not functioning properly, the surgeon should ensure that no soft tissues are entrapped. It is recommended to perform the forced duction test under sedation, local anesthesia, or general anesthesia.

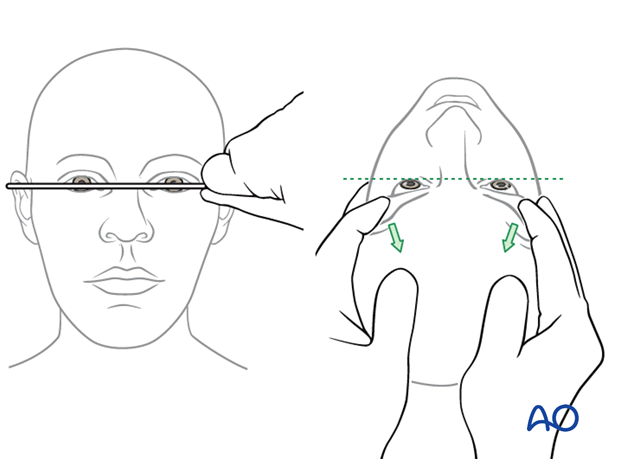

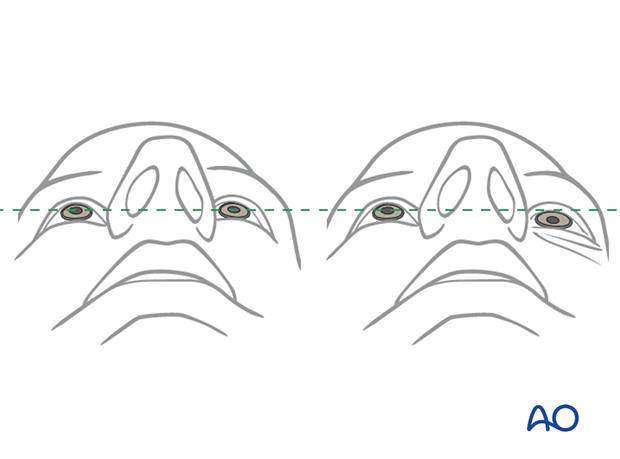

Globe position

Simple testing of the pupil axis is provided using a straight instrument. Additional comparison of light reflexes might be helpful.

The examiner should include an examination from above to evaluate globe position.

Globe position should also be evaluated from below.

The illustration on the right shows a posttraumatic asymmetry of globe position (left enophthalmos).

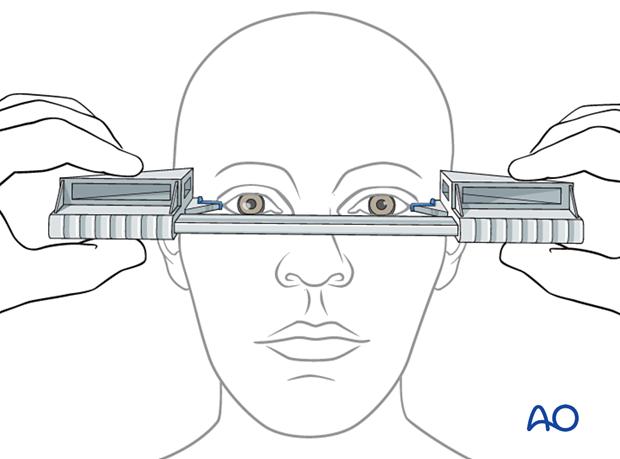

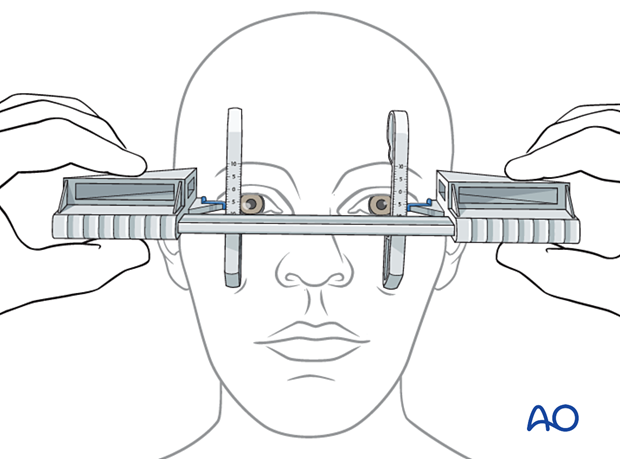

This instrument is only reliable for measuring the sagittal globe position correctly in a side-to-side comparison if the lateral orbital rim is intact and not displaced. In these cases, the amount of en- or exophthalmos can be measured reliably.

A Hertel exophthalmometer is misleading in case of acquired or congenital asymmetry of the lateral orbital rims (see above). A Naugle exophthalmometer is preferred in these cases since the referring structure is not the lateral orbital rim but the frontal and infraorbital structures.

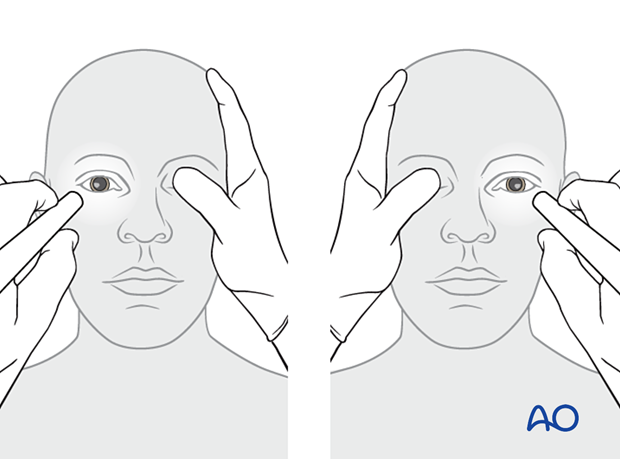

Pupillary reaction

A light is used to assess the pupillary reaction.

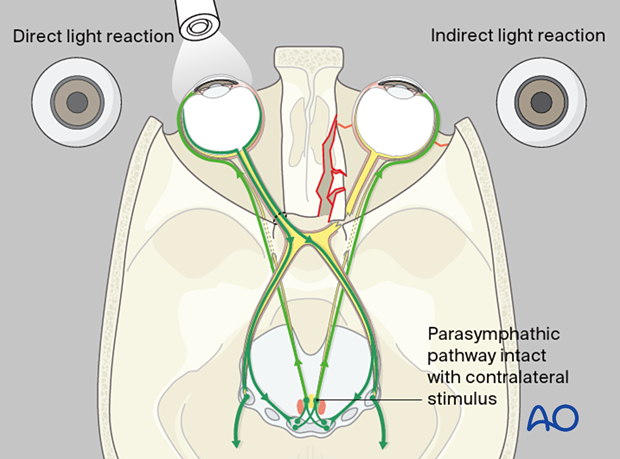

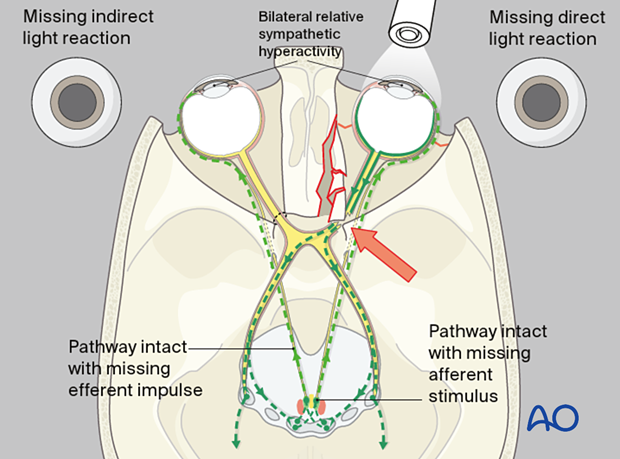

Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

A relative afferent pupillary defect can be detected with light moving from one pupil to the other. In a conscious or unconscious patient with no drug-related compromise of pupillary function, this test provides a reliable assessment of whether an afferent disorder of the visual system is present.

When neither the RAPD nor the pupillary reaction test can be performed, a Visual evoked potential (VEP) may be appropriate.

The illustration shows the optic nerve with impingement at the orbital apex. There is no indirect light reaction of the unaffected right eye (Marcus Gunn pupil).

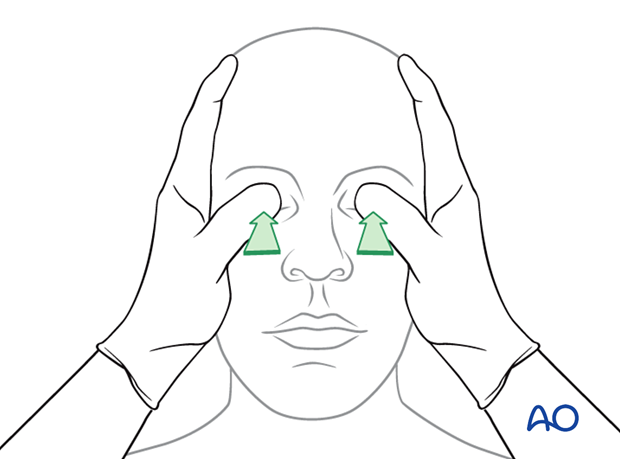

Gross digital intraocular pressure testing

The illustration shows gross digital intraocular pressure testing.

If a patient has sustained significant periorbital trauma, an ophthalmologist's examination should be performed pre- and postoperatively. It should include an examination of the anterior chamber to rule out a hyphema.

The exam should also include a bright light exam with dilation of the pupil for a complete examination of the retina. Special consideration should be made to rule out retinal detachment by careful examination of the optic nerve using a bright light examination with a dilated pupil.

Severe exophthalmos due to retrobulbar bleeding may need immediate surgical intervention to decrease the intraorbital pressure. Preoperative radiological assessment is mandatory in cases of pulsating exophthalmos, which is typical for carotid-cavernous-sinus fistula.

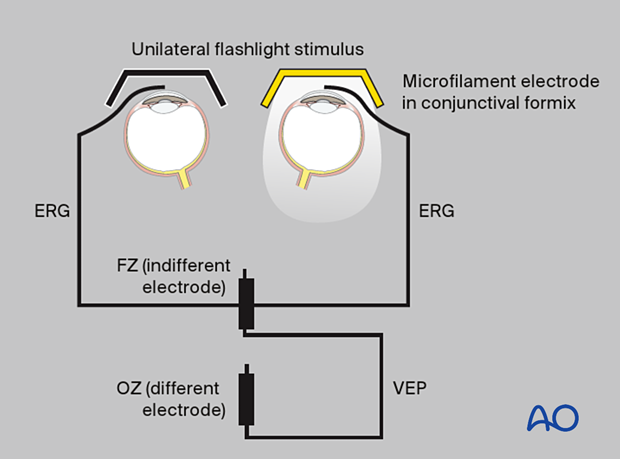

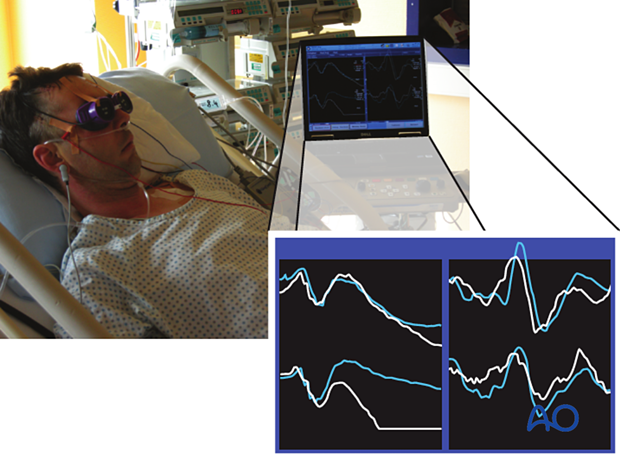

Visual evoked potential (VEP)

Although this technique has been available for decades, it is not yet part of the clinical routine.

Especially in an unconscious patient where no reliable information on RAPD is available, electrophysiological testing can be performed in the emergency room, on the ward, or even intraoperatively if an electrophysiological setup for this testing is available. An electroretinogram (ERG) together with a VEP must be recorded for each eye. The ERG is essential to prove that the retina functions and generates an appropriate electrical signal transduced via the optic nerve toward the visual cortex (VEP).

The stimulator consists of goggles or a light source that stimulate one eye at a time. In the author's experience, the signal is averaged out of 100 singly recorded evoked potentials recorded in parallel for the retina (ERG) and the cortex (VEP). Each series of recordings takes 100 seconds. For each eye, the recording process must be repeated to validate the evoked potentials. Later, the amplitude and latency of the electrical visual responses can be analyzed. This examination should be performed by an experienced electrophysiologist.

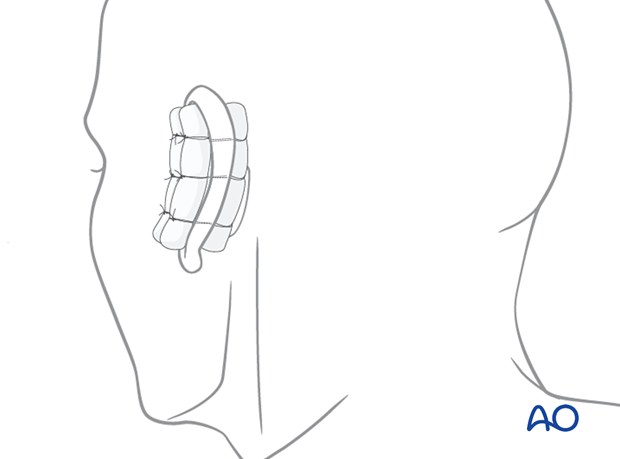

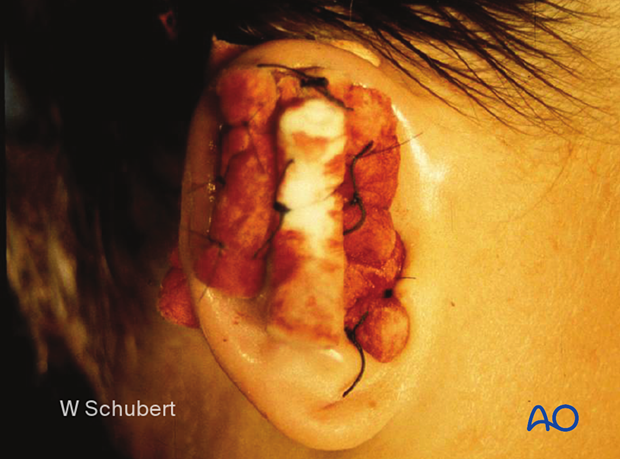

6. Ear examination

Examine the ear for a hematoma of the auricular cartilage. If there is a hematoma, it must be drained, and a "through-and-through" bolster dressing is recommended. This is to prevent the permanent deformity resulting in a “cauliflower ear”, with possible compromise of the external canal.

Bolster sutures are used in a "through-and-through" manner to prevent reaccumulation of the hematoma.

Many different materials can be used for a bolster dressing. In this case, dental rolls have been used.

Examine for blood and CSF leakage (which may be seen with a skull base fracture).

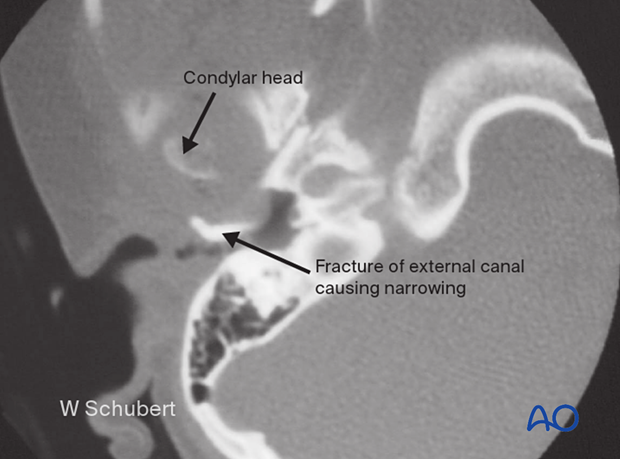

Examine for laceration or collapse of the external canal.

Examine the tympanic membrane for rupture or a hemotympanum (involve otorhinolaryngologist for examination).

This CT shows a child following impact on her mandibular symphysis, driving the condylar head into the external ear canal. The patient presented with narrowing of the canal and hemotympanum.

7. Nasal examination

Examination of the nose starts with inspection for swelling or asymmetry, followed by palpation. Characteristic signs for nasal fractures are:

- Pain

- Bleeding

- Swelling

- Compromised nasal airway

- Crepitation

- Palpable bony dislocation

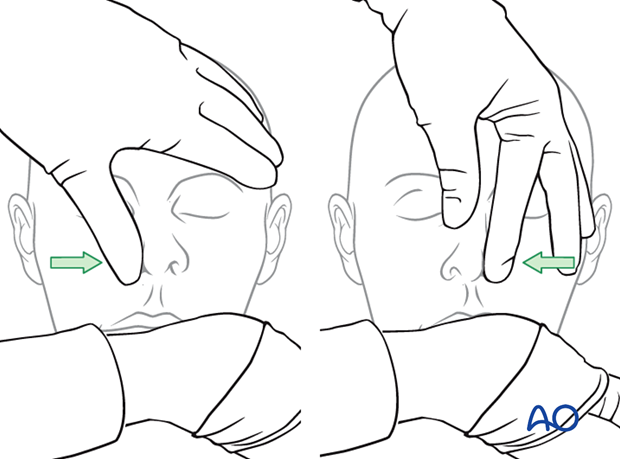

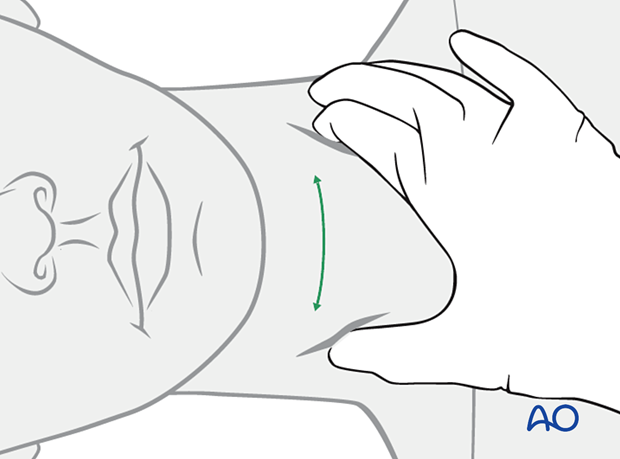

The illustrated testing of the nasal airway passage (see illustration) is a simple method to gather information on the nose's internal patency function and septal or turbinate injuries.

If the nasal airway passage is compromised, the reason must be investigated.

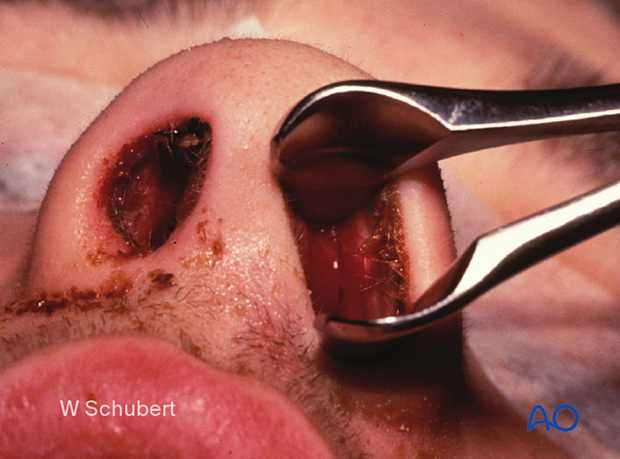

Nasal inspection using a speculum with appropriate light (headlights are recommended) allows for examining the nasal cavity. Additional nasal endoscopy should be performed if further clinical examination of more posterior nasal structures is indicated.

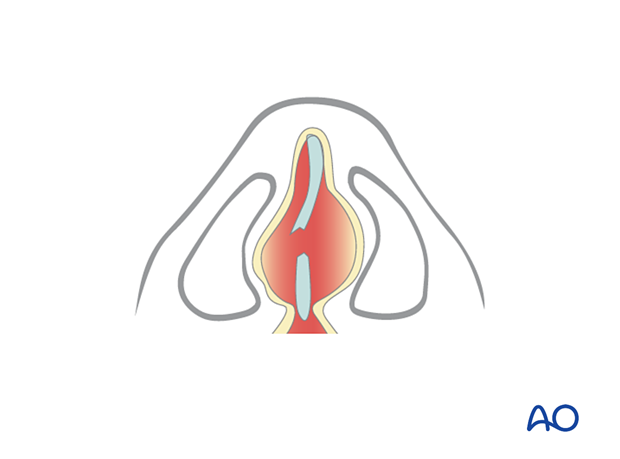

It is very important to rule out and treat any septal hematoma, as these must be drained to avoid infection and septal perforation. Nasal packing or internal nasal splints are inserted to prevent recurrence of the hematoma.

This clinical photograph shows a septal hematoma.

The clinical photograph shows delayed drainage of septal hematoma resulting in infection. This patient did not present to the emergency room until one week after sustaining nasal trauma.

An undetected septal hematoma may also result in neocartilage formation, resulting in widening of the septum and narrowing of the nasal airway.

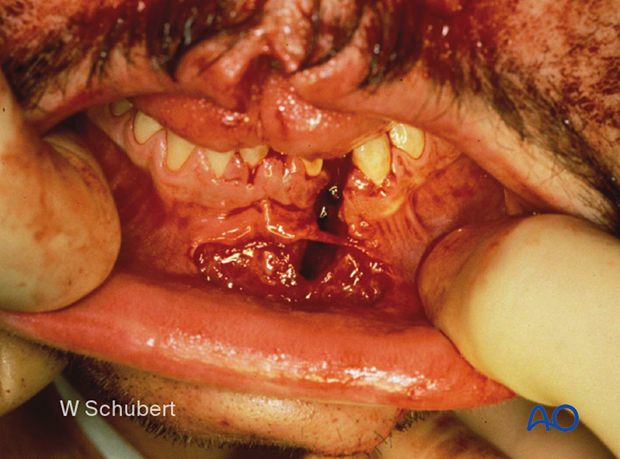

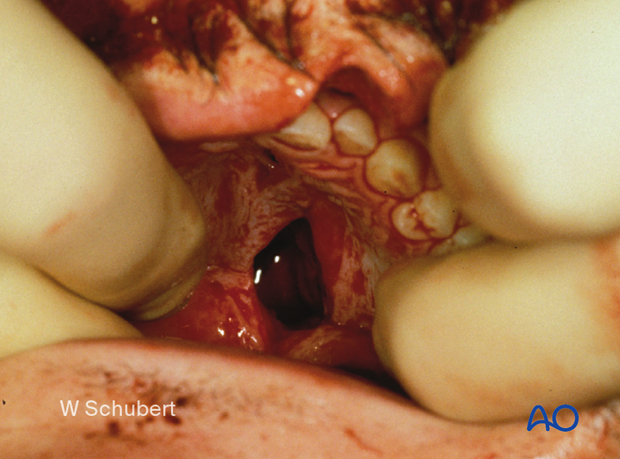

8. Oral/throat examination

Intraoral inspection

Look for:

- Open fractures

- Asymmetries

- Hematoma

- Lacerations of soft tissues and gingiva (including salivary ducts)

- Foreign bodies

- Avulsed and luxated teeth

- Malocclusion

- Occlusal irregularities

Intraoral palpation

Intraoral palpation should include the following:

- Bimanual manipulation of mandibular and maxillary segments, gingiva, and teeth to identify dental mobility or mobile fragments

- Palpation of bony steps at the zygomaticomaxillary buttress

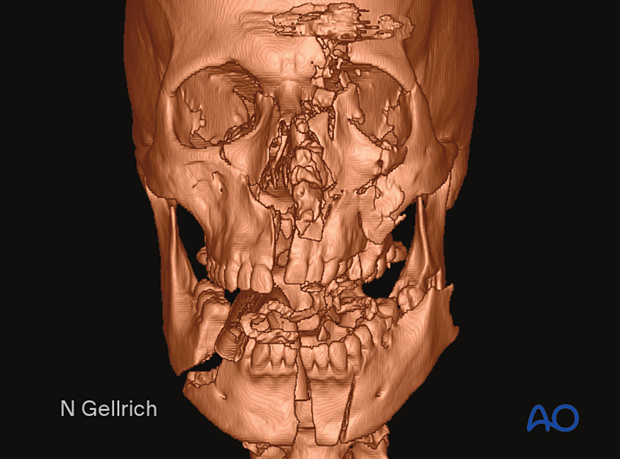

This panfacial fracture shows a characteristic anterior open bite deformity commonly associated with Le Fort fractures (rule out bilateral condylar fractures, which can also lead to an anterior open bite). Multiple dentoalveolar injuries are present.

The clinical photograph shows an additional full-thickness lip laceration which commonly accompanies palate fractures.

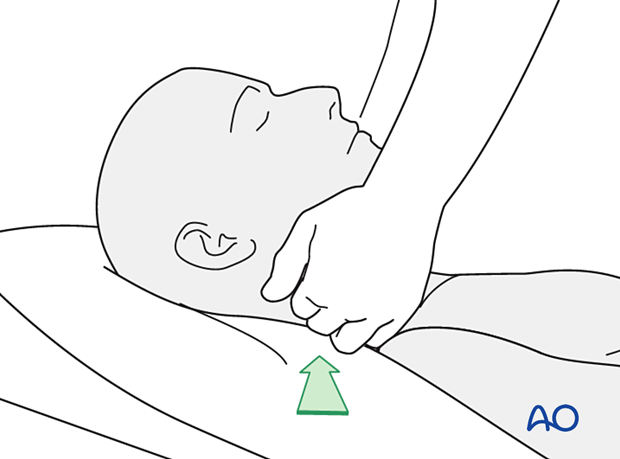

9. Neck examination

Palpate the posterior neck for any signs of cervical spine trauma.

This shows a patient with a severe cervical spine injury.

Palpate the anterior neck for signs of laryngeal trauma. A missed laryngeal fracture can result in soft-tissue swelling and a hematoma, resulting in rapid loss of the patient's airway. Placement of an endotracheal tube may be difficult or dangerous if a patient has a large hematoma. ICU observation of the airway and possible emergency tracheostomy should be considered. Elective intubation for midface surgery should be delayed.

If a laryngeal fracture is suspected, obtaining a CT of the neck is recommended. This CT demonstrates a fracture of the thyroid cartilage.

Examine for any significant penetrating neck trauma or laceration.

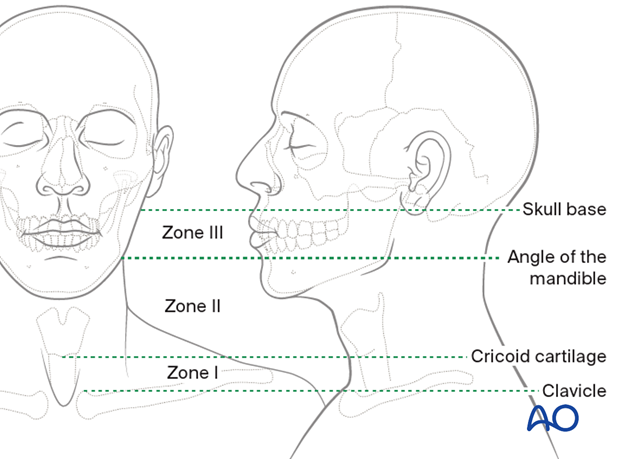

Zones of penetrating neck trauma:

- Zone I: From clavicle up to the level of the cricoid cartilage, it is treated as an upper thoracic/neck injury

- Zone II: From cricoid cartilage up to the angle of the mandible, it is considered an upper neck or face injury

- Zone III: From above the mandible angle up to the skull base, it is treated as a facial injury but may include the skull base, frontal bone, or brain

10. Sensory and motor examination of the face

Examine the function of the facial sensory nerves, branches of the trigeminal nerve (supraorbital nerve, infraorbital nerve, and mental nerve).

Branches of the cervical nerves such as the greater auricular nerve may also be involved.

Examine the function of the facial motor nerves (frontal (temporal), zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and the cervical branch of the facial nerve). The most important branches to check are the zygomatic and the marginal mandibular.

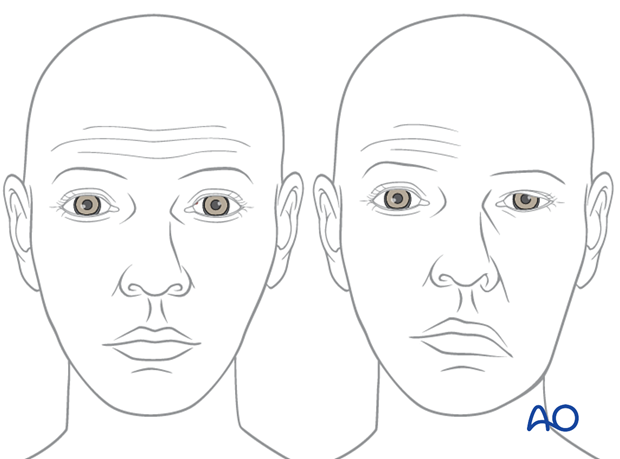

The illustration shows injury to the orbital and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve, resulting in an inability to close the left eye.

The illustration shows absence of function in the left depressor muscles, resulting in lower lip asymmetry due to marginal mandibular nerve damage.

The illustration shows injury to the left temporal branch resulting in significant brow ptosis, inability to wrinkle the forehead, and possible visual field impairment with upward gaze.

11. Fracture palpation

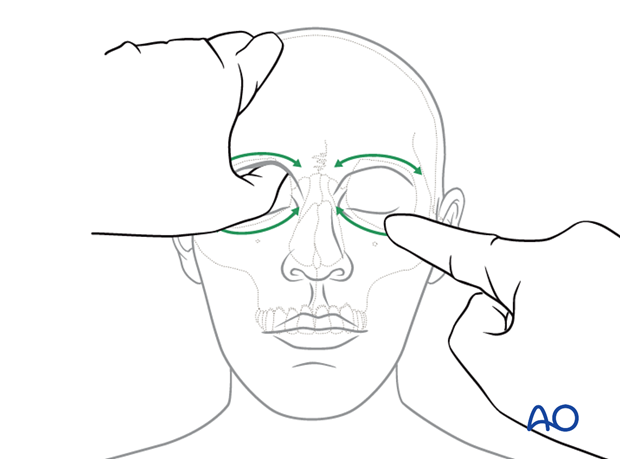

The midface and frontal cranium should be palpated to detect bony irregularities, step-offs, crepitus, and sensory disturbances.

It is crucial for decision-making to ensure that one hand stabilizes the skull so that the examiner's contralateral hand can provide movements that can be assessed.

The illustrations show the midfacial skeleton's step-wise examination focusing on fracture end movement at the infra- and supraorbital rims.

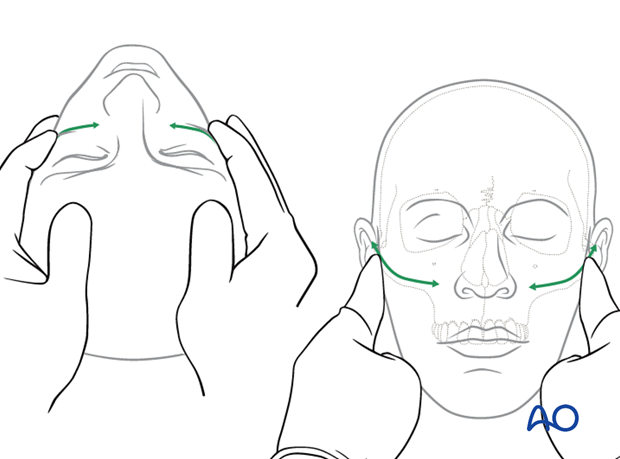

This illustration shows palpation of the nasal bones.

This illustration shows palpation in the region of the zygomatic complex and zygomatic arch.

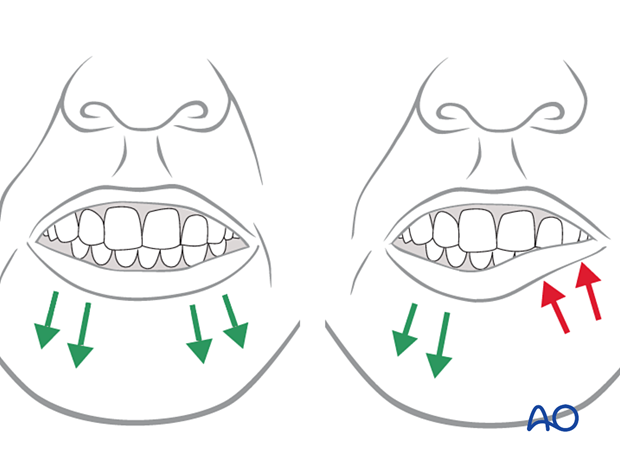

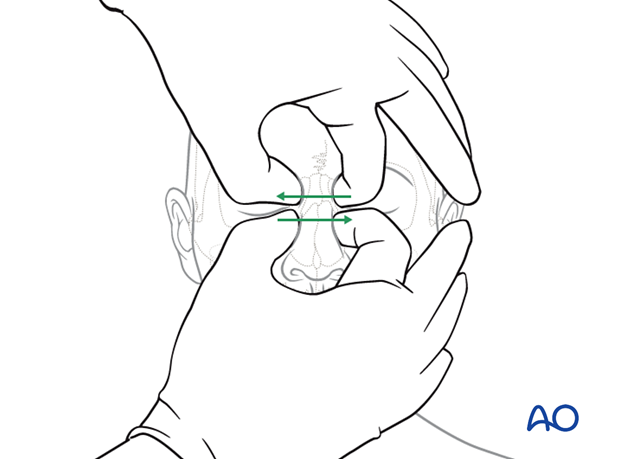

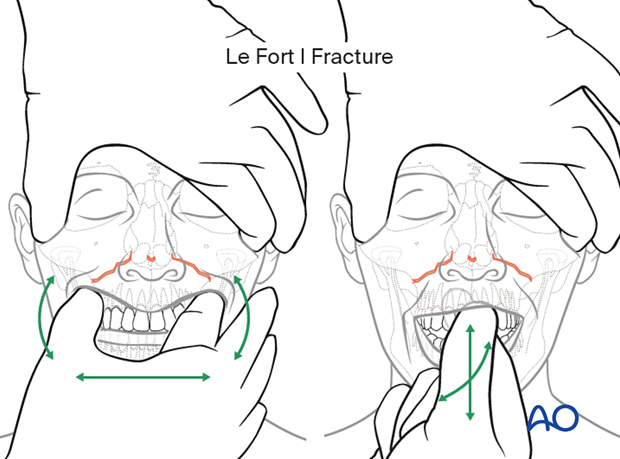

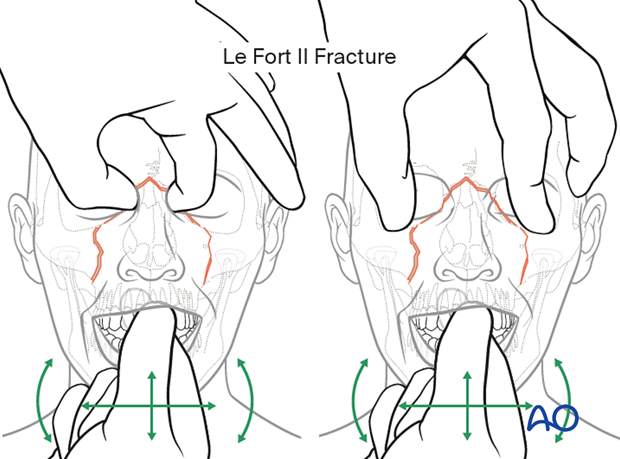

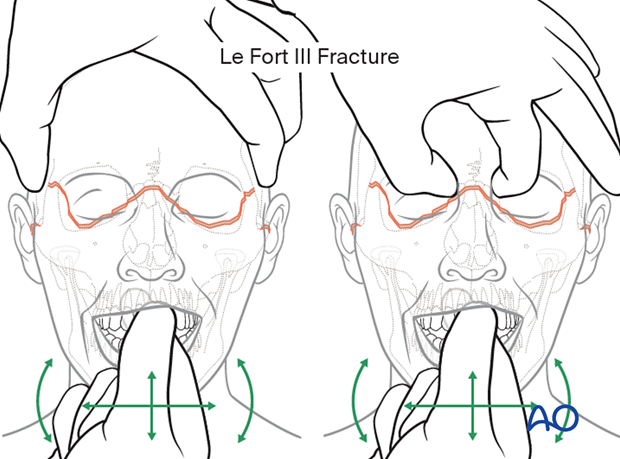

This illustration shows testing for mobility of the maxilla.

Mobility of the midface may be tested by grasping the anterior alveolar arch and pulling forward while stabilizing the patient with the other hand.

The level of a Le Fort fracture (ie, I, II, III) can often be determined by noting midface structures that move in conjunction with the anterior maxilla.

This illustration shows testing for mobility of the central midface.

This illustration shows testing for mobility of the midface.

12. Radiological findings

Before CT imaging, 2D x-rays had been considered adequate for pre- and postoperative diagnostics in orbital floor fractures. One of the great weaknesses of plain film is that although it reveals the fracture, it does not always show the degree of fracture displacement.

With CT and CBCT imaging, the surgeon can better define fractures, the degree of fracture displacement, and the need for accurate reduction.

CT or cone-beam-based radiological examination should be performed to assess the individual type and extent of a fracture.

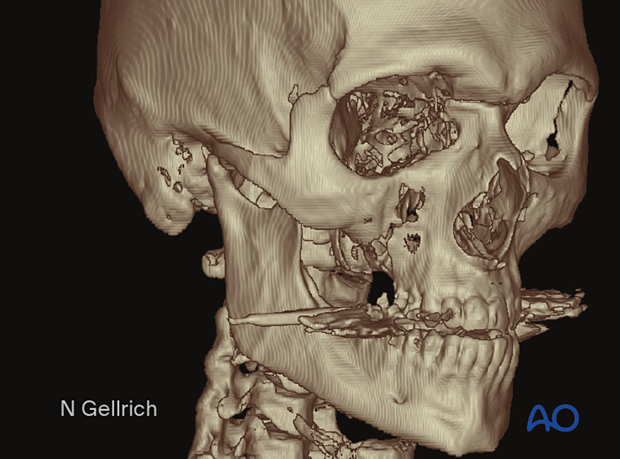

This 3D CT scan shows a panfacial fracture, but it may not reveal the detail obtained in specialized (coronal and sagittal) 2D slices.

CT scanning

Recommended scanning protocol for CT includes:

- 2–3 mm slice thickness (orbital fractures: 1 mm)

- Gantry = 0°

- Hard- and soft-tissue window rendering

- Field of view: complete skull (to visualize possible accompanying fractures or scan for potential donor sites in bone grafting procedures), including the cervical spine

This CT scan shows a 3D image of a Le Fort III fracture.

Note that metal dental fillings produce scatter artifacts.

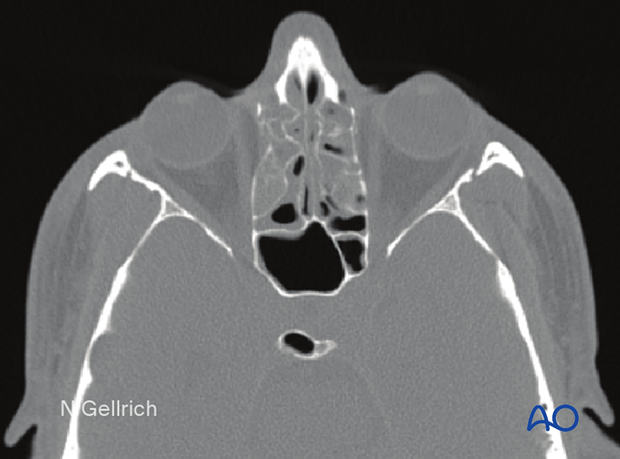

Axial CT scan of the same patient through the upper nose and orbit.

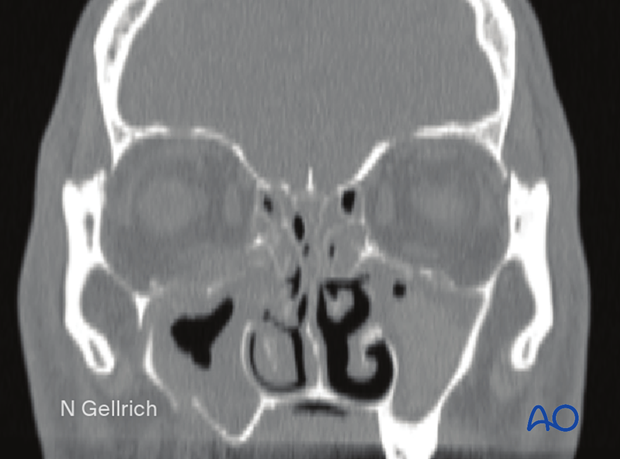

Coronal CT of the same patient imaged at the posterior margin of the globe.

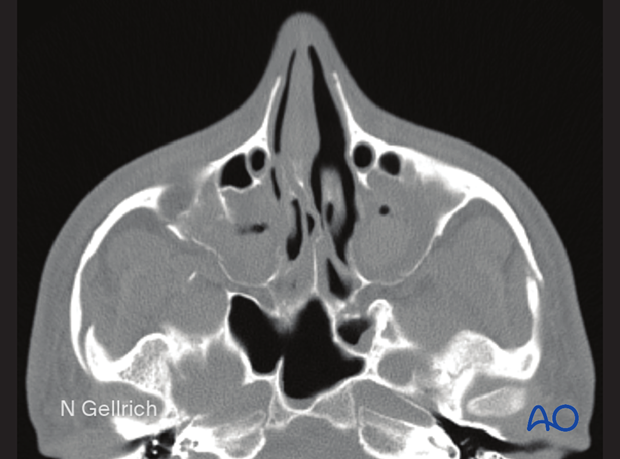

Axial CT through the interior orbital rim and zygomatic arches in the same patient.

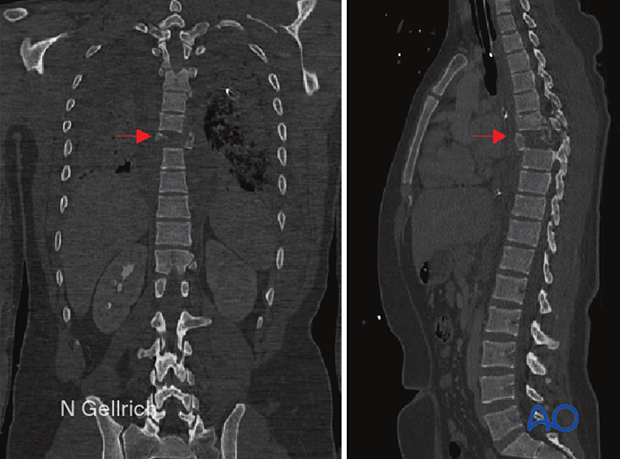

In total body scans of the polytrauma patient, concomitant injuries can be detected.

Obtaining thin axial CT slices allows the surgeon to reformat coronal, oblique, and parasagittal views. The surgeon can also obtain reformatted 3D views.

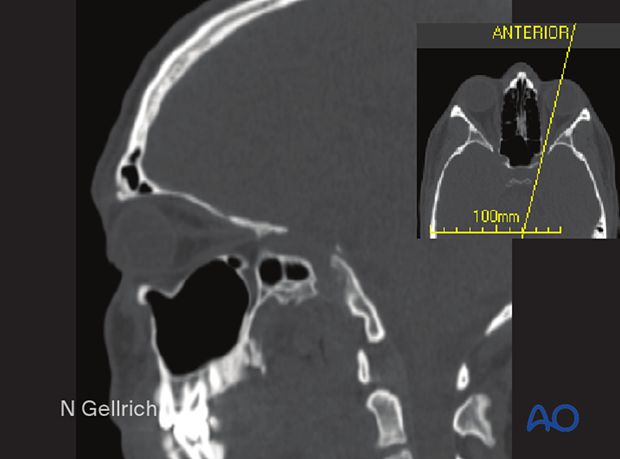

This image shows an oblique parasagittal view in the longitudinal axis of the optic nerve. It provides excellent visualization of the orbital roof, the orbital floor, and the optic nerve. A thorough CT evaluation is considered the standard of care for midface fractures.

Cone-beam technology

Cone-beam technology allows adequate determination of hard-tissue problems but is not equivalent to CT technology in soft-tissue assessment (eg, retrobulbar hematoma). A further limitation of cone-beam technology is a more limited scanning region.

Cone-beam technology is becoming more important for pre-, intra- (3D C-arm), postoperative imaging, and virtual surgical planning.

Because there is less radiation exposure, a cone-beam scan may be more suitable for postoperative control.

13. Conventional imaging (plain x-rays)

Most centers have CT facilities and therefore seldom obtain plain films. Some centers find a postoperative AP and lateral view useful for documenting plate and screw placement.

2D imaging can include the following:

- Waters’ view: This was a plain x-ray used for visualizing sinus fractures before CT became readily available. It offers poor visualization of fractures and does not provide the surgeon with adequate information about fracture displacement.

- Orthopantomogram (OPG): This is a standard view normally used for the mandible, but it can also provide information regarding the midface.

- Lateral view (cephalic).

- Submentovertex view (Jug handle view): For zygomatic arch injuries.

Plain films lack precision for determining the sagittal extent of injuries. Treatment for midfacial fractures based on 2D imaging risks underestimating the severity of the injury. This may result in later deformities such as enophthalmos or hypophthalmos, which can be avoided by careful evaluation of the preoperative CT scan.

14. Radiological diagnosis of midfacial fractures: special considerations

Special scanning procedures might be necessary if the anterior or lateral skull base is involved and, particularly, for detecting or controlling CSF-fistula or aneurysms. Fine slices may be considered for the petrous portion of the temporal bone, particularly when there is paralysis of the facial nerve.

In the event of accompanying dental trauma with missing tooth parts or empty alveolar sockets, it is crucial to determine the missing elements' location. For dislocations of teeth into the jaws, a standard orthopantomogram (OPG) is helpful. If the missing tooth or tooth parts cannot be localized, additional radiographs of the upper and lower airways (including frontal and lateral cervical x-ray, frontal and lateral chest x-ray) and upper and lower gastrointestinal pathways should be considered. Additional endoscopic measures may be considered in retrieving dislocated dental fragments.

15. MRI

MRI might be indicated to assess certain soft-tissue problems such as:

- Optic nerve edema or hematoma

- Ocular muscle disorders (incarceration, hematoma, disruption)

- Intraocular disorders (hematoma)

- Foreign bodies in the orbit

In rare indications, ultrasound may be indicated to detect intraocular or intraorbital disorders, eg, hematoma, or foreign body.