Panfacial fractures (sequencing of repair)

1. Introduction

Sequencing of repair

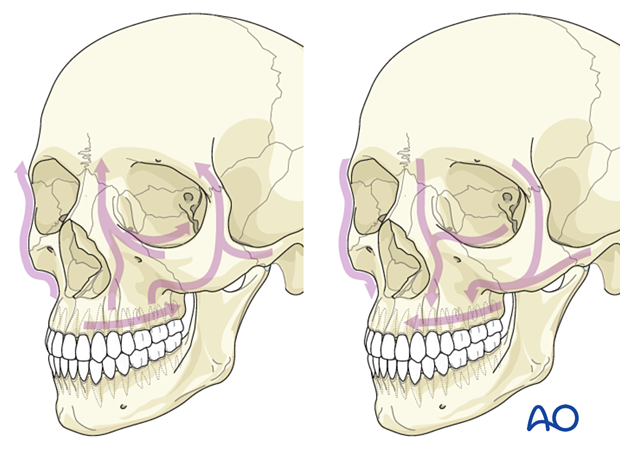

There are several schools of thought for organizing the repair of panfacial fractures:

- Bottom-top, outside-in

- Top-bottom, inside-out

- Beginning in the upper or lower face with the occlusion or frontal bone and progressing through the frontal and upper midface unit or the occlusion and the mandible and then linking them at the Le Fort I level

The determination of ideal sequencing of a complex panfacial trauma to establish a facial frame in all dimensions can be the greatest challenge to a craniomaxillofacial surgeon because panfacial fracture results in a lack of reliable bony and soft tissue landmarks. Failure to achieve proper reduction results in a posttraumatic facial deformity. Sequencing serves as a guide for stepwise management and assists in achieving facial symmetry.

Timing of repair

Timing of repair should proceed as soon as clinically feasible. The two published timings for the organization of repair of panfacial fractures are early and late intervention. Late intervention allows deformity and dislocation to heal in the wrong position and soft tissue to mold and scar over dislocated facial bones. Late intervention fixes the deformity, and it may be difficult to reestablish the preinjury form and appearance. Late intervention can cause secondary injury to the weakened soft tissue, and it is more complex as fracture callus formation and fibrous tissue may compromise functional and esthetic outcomes.

Early stabilization of fracture segments restores symmetric preinjury facial contours. Of course, life-threatening injury should be given priority.

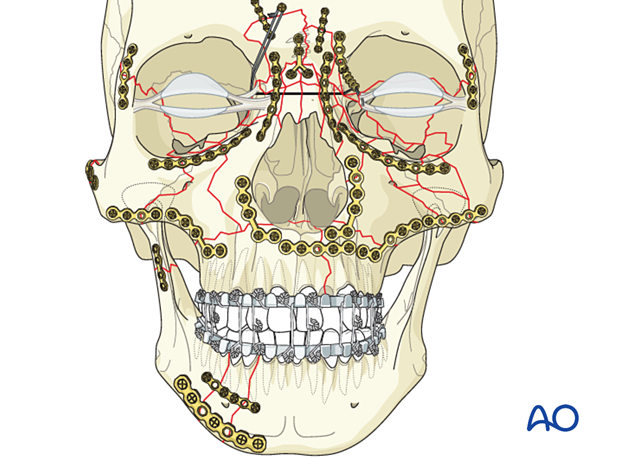

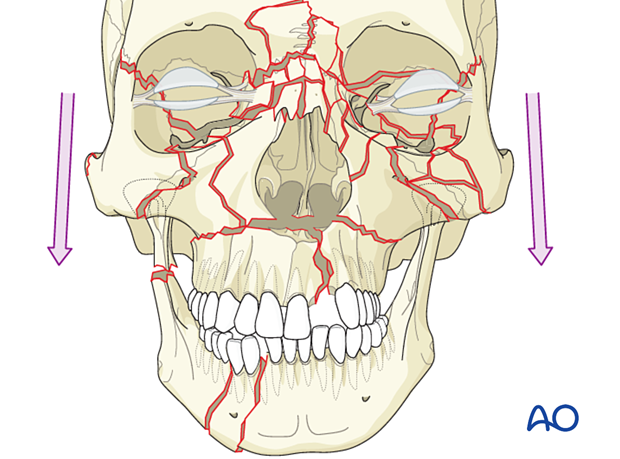

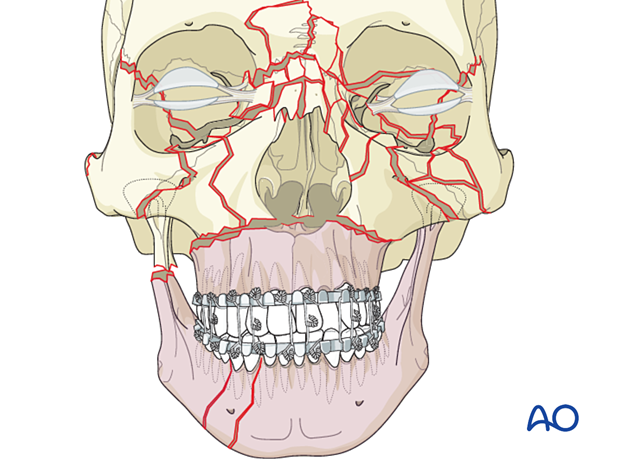

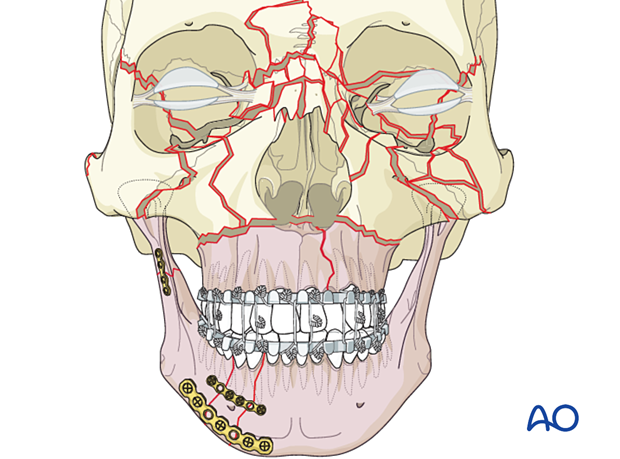

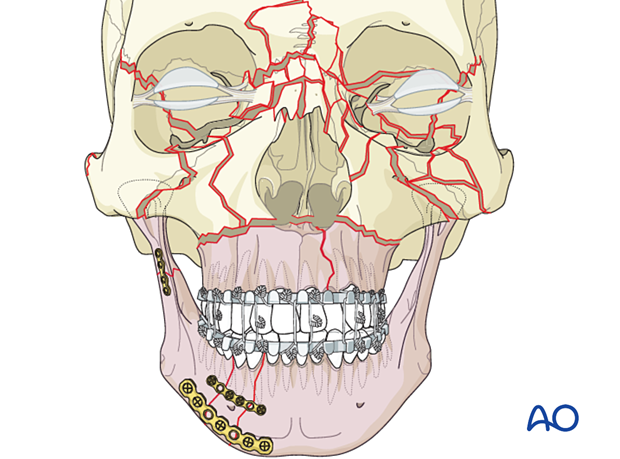

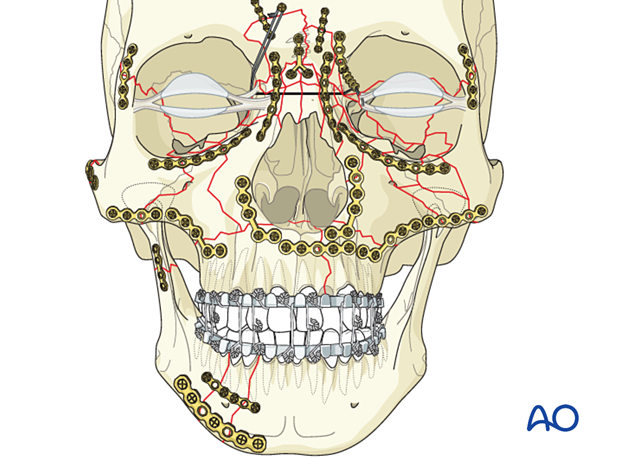

The illustration represents most commonly-seen facial fractures.

It represents the following fractures:

- Le Fort I

- Le Fort II

- Le Fort III

- Frontal sinus

- Nasal

- Bilateral NOE

- Bilateral zygoma

- Bilateral orbit including the medial and lateral wall, and orbital floor and roof

- Simple sagittal split of the palate

- Segmental mandibular body/parasymphyseal

- Unilateral fracture of the condylar process

2. Principles

Goal

The goal is to restore the anatomy of the bone in three dimensions, stabilizing the maxillofacial buttresses by rigid fixation wherever necessary. The buttresses provide resistance to external forces and give structural support by absorbing the forces acting on the facial skeleton.

One of the most significant advances in managing panfacial fractures is the recent use of 2D and 3D CT scans, which enable surgeons to perform pre-operative and virtual surgical planning to achieve optimal esthetic and functional outcomes. This allows individual assessment of injuries and is a prerequisite for optimal diagnosis, planning, reduction, and outcome control.

Radiographic evaluation should not be restricted to 3D views since multiplanar 2D views also show critical features that are important for treatment.

The rapid prototyping or 3D printing of skull models after virtual surgical planning has further enhanced the craniomaxillofacial surgeon’s ability to achieve an optimal surgical outcome.

Three options for sequencing

There are three options for sequencing:

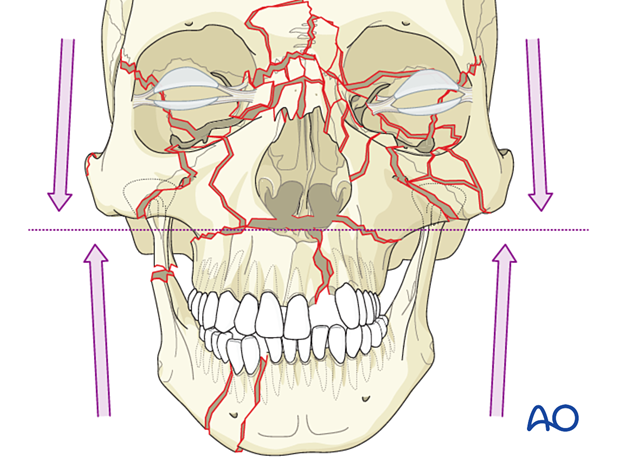

- Reestablish the maxillo-mandibular unit as the first major step of the sequencing (bottom-up).

- Start with reduction and fixation at the calvarium level and proceed in a caudal direction (top-down).

- Divide the face into upper and lower halves (at the Le Fort I level) and begin either with MMF in the lower face unit or with the frontal bone in the upper facial unit.

Once the maxillomandibular unit is established, most surgeons start from the calvarium and proceed in a caudal direction with reduction and fixation.

It should be noted that with this second option of sequencing, the reestablishment of the proper maxillomandibular unit is still very important but may be achieved later in the case.

Open reduction proceeds through each unit, and the two units are linked finally at the Le Fort I level.

Reestablishing the maxillo-mandibular unit as a first priority

In the following description, we focus on the first sequencing method, reestablishing the maxillomandibular unit as the first priority.

The first step is to focus on the reestablishment of the maxillomandibular unit.

If there is a Le Fort type fracture but no sagittal split of the palate and no mandibular fracture, the maxillomandibular unit's reestablishment should be fairly simple, using arch bars and MMF.

If there is a Le Fort type fracture, no sagittal split of the palate, and mandibular fractures, the establishment of the correct mandibular dental arch configuration can be obtained using the intact maxillary dental arch through MMF.

A discussion of multiple mandibular fractures is provided in the CMF Mandible module.

If there is a Le Fort type fracture with a sagittal split of the palate, and no mandibular fractures, the mandibular dental arch may be used as a guide in reestablishing the occlusion and width of the maxillary dental arch with the placement of arch bars and MMF.

The recommended sequence for this portion of the palate treatment depends on whether it is a simple or complex (comminuted) palatal fracture.

Refer to the treatment pages for simple and comminuted palatoalveolar fractures for more information on the treatment of these injuries.

If there is a Le Fort type fracture and a sagittal split of the palate together with mandibular fractures, the reestablishment of the disrupted dental arches' proper width is more complicated. The surgeon must reconstruct one dental arch and use it as a template for the other. The palate can be stabilized with open reduction and is utilized as a template for patterning the mandibular dental arch and occlusion.

This can be done in two ways: either through anatomic reduction or by using model surgery on dental casts and fabricating splints.

It can also be done with virtual surgical planning, and splints can be fabricated by rapid prototyping or 3D printing (CAD-CAM).

Anatomic restoration of the maxillary dental arch by surgical open reduction consistently gives the most accurate results and forms a pattern for the width of the mandibular dental arch. Model surgery and dental splints start with an approximation of maxillary and mandibular normal width and are generally not as accurate as open reduction of the palate as a guide to mandibular width.

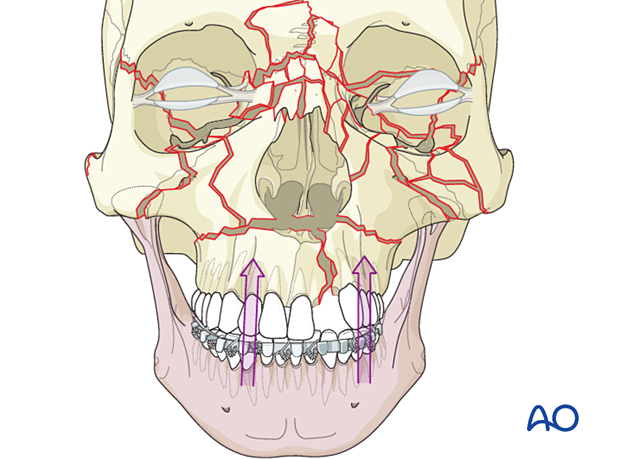

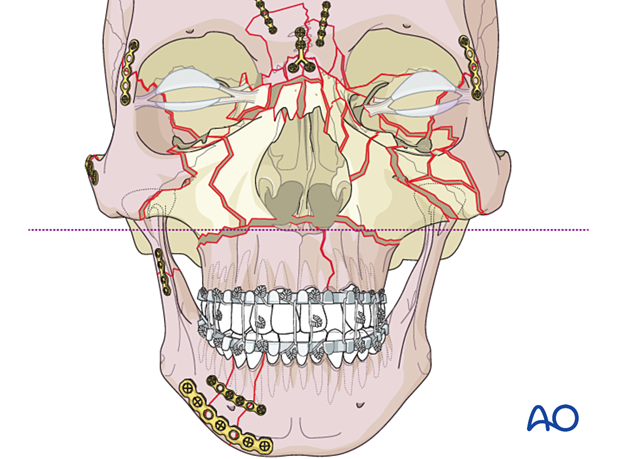

In the illustration, the mandible was anatomically reconstructed and used to restore the maxilla's width through MMF (first option).

A second, less accurate, option involves taking dental impressions, making dental casts, and from these models, arriving at a determination of width of the maxilla and the mandible. This determination is seldom as accurate as anatomic reduction with internal fixation beginning with the maxilla.

In these complex cases, segmentation of the maxillary and the mandibular dental models is used to recreate the fractures and perform “model surgery” to determine the dental arch form and pre-morbid occlusion and contour of the maxillary and mandibular arches.

Once the maxillary and mandibular model surgery has been performed, palatal and/or mandibular splints are fabricated for use during surgery.

This technique may also be considered if either the palatal fracture(s) or mandibular fracture(s) are very complicated, but the other portion of the maxillomandibular unit is intact. The surgeon may choose to use dental impressions and models with any complex fracture involving the dentition where proper premorbid occlusion is uncertain.

A digital impression can also be taken with an intraoral scanner (optical scan) that is then transferred to the computer software, where virtual surgery can be performed to reestablish the premorbid occlusion. This is a complex process not readily available in many centers.

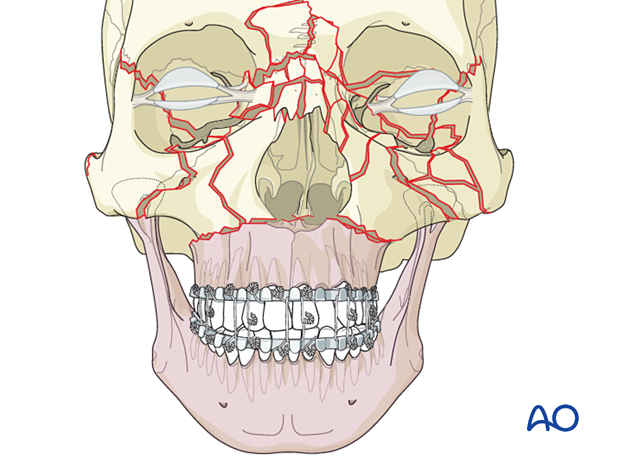

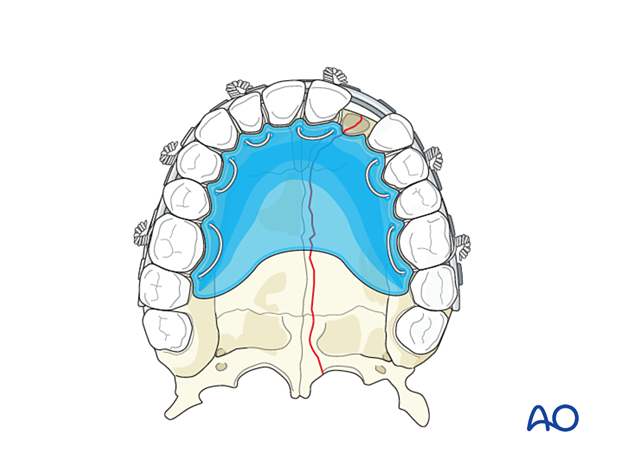

The illustration shows an example of a palatal splint that has been prefabricated after model surgery. Circumdental wires are ligated to the arch bars to restore the maxillary arch form.

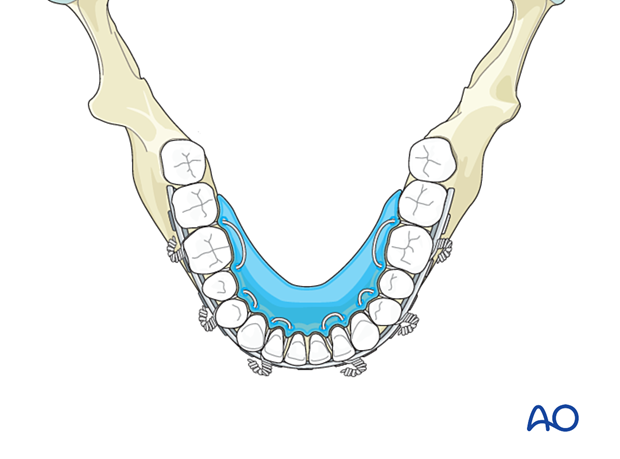

If a mandibular lingual splint is needed, it is fabricated and fixed to the mandible, using arch bars and wires.

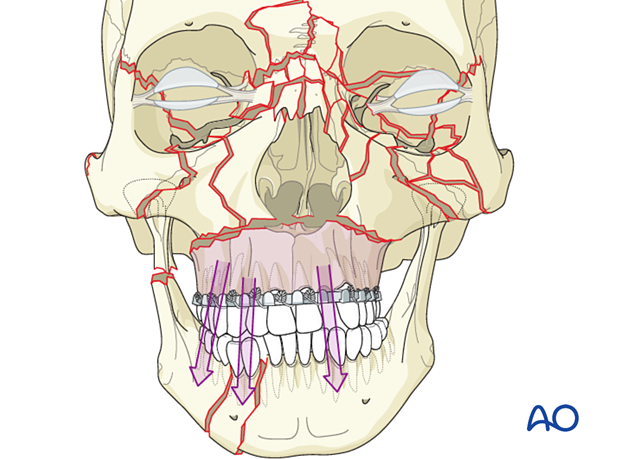

The illustration shows an example of a lingual mandibular splint that has been prefabricated after model surgery. Circumdental wires are ligated to the arch bars to restore the mandibular arch form.

In cases where there are condylar fractures, open treatment of these fractures will restore proper mandibular height and chin position.

In this illustration, the mandible was reduced and fixed and then used as a guide for reducing the palate.

Summary

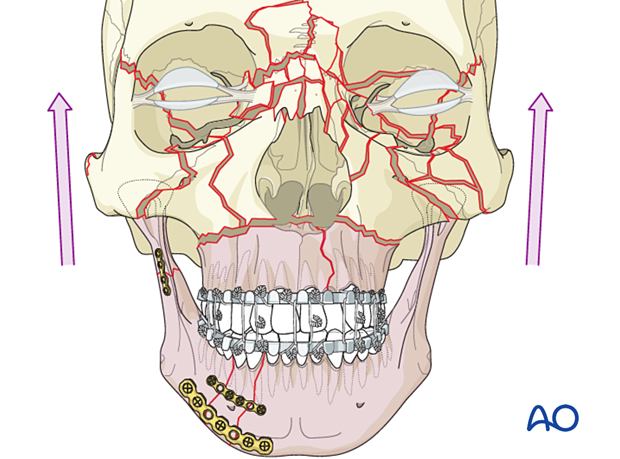

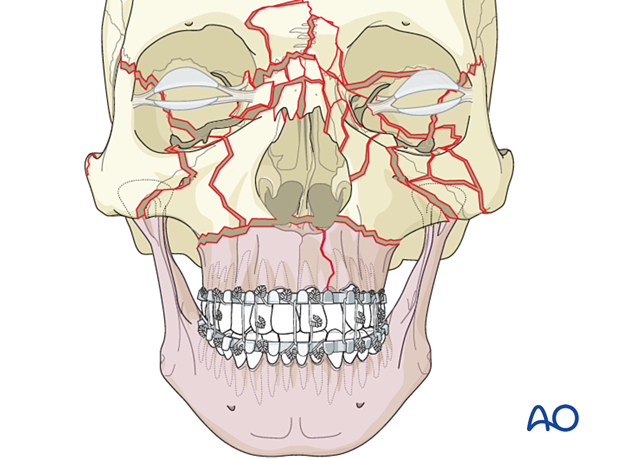

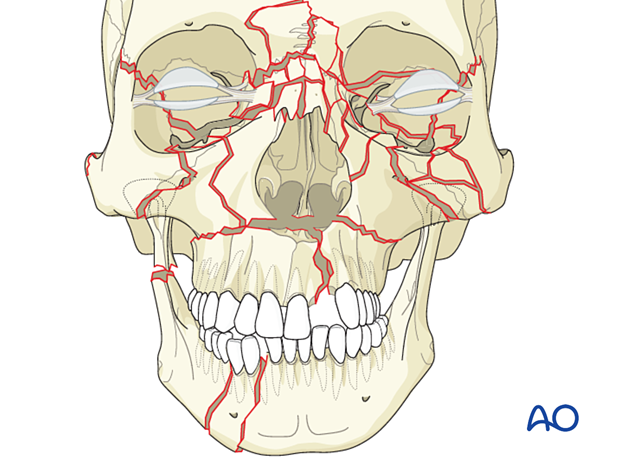

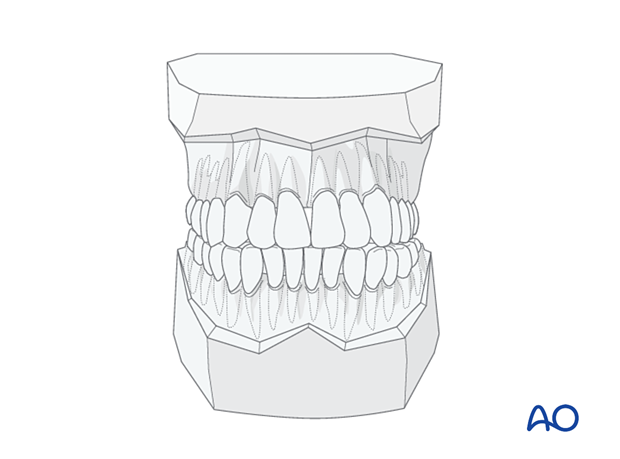

The proper maxillomandibular unit has been restored with the proper premorbid occlusion with a combination of the modalities described.

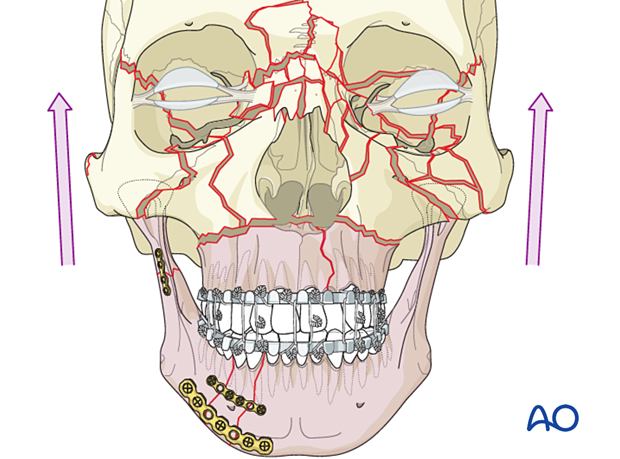

The next step is to reduce and fix the remainder of the midface, starting from the calvarium and working in a caudal direction. (Refer to top-down procedure for details).

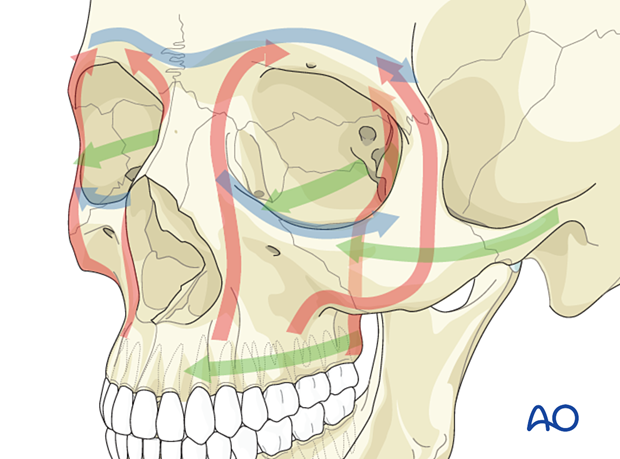

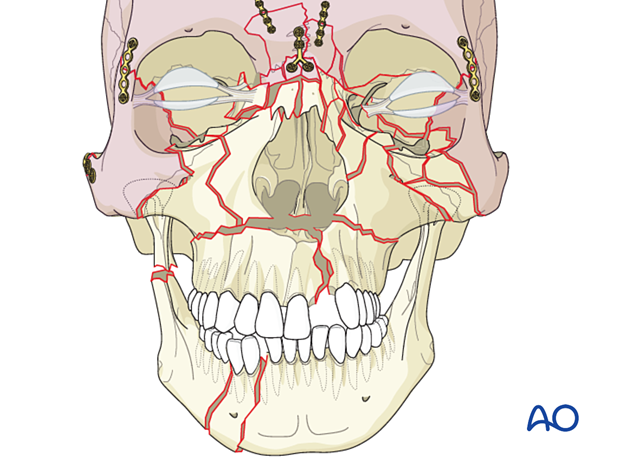

3. Sequencing from the calvarium down

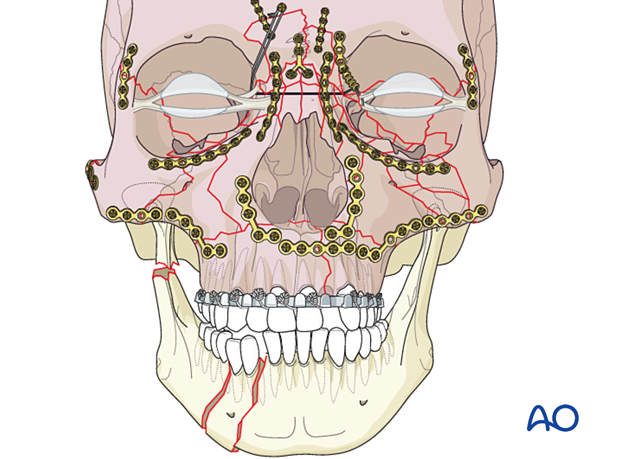

The reconstruction sequence to reestablish midfacial pillars (buttresses) and dimensions starts with the most reliable reference structures and on the side with the least comminution.

The priority is to address any significant calvarial, frontal sinus, and orbital roof fractures. Using the calvarium as the foundation for the remainder of the midface reconstruction, the surgeon progresses from this level down to the Le Fort I level. The fractures at the Le Fort I level are the second to last fractures to be plated.

The zygoma is positioned into its proper three-dimensional position to correctly line up the orbit's lateral wall with the sphenoid's greater wing.

Refer to the treatment page for zygomatic complex fractures for more information on the treatment of these injuries.

The proper alignment of the zygomatic arch and the infraorbital rim must be considered during the reduction of the various fractures.

The completion of the reconstruction of the periorbital areas is performed by addressing the NOE and nasal fractures.

The next step in midface reconstruction is fixation across the Le Fort I level.

If everything has been correctly aligned, the Le Fort I fractures should also align perfectly. If a patient has a malalignment at the Le Fort I level, the surgeon needs to reassess the other fracture alignments and consider a correction.

From an esthetic standpoint, a minimal malalignment at the Le Fort I level is not as noticeable as the orbits' malalignment. The surgeon needs to decide whether the malalignment at the Le Fort I level will be associated with occlusal problems.

The last fractures to be reconstructed are generally the fractures of the orbital walls and orbital floor.

Maxillomandibular fixation is now performed, and the mandibular fractures are repaired.

Any condylar fractures may be treated open or closed depending on the surgeon’s decision.

The occlusion should be rechecked at the end of the case. The surgeon needs to decide whether to leave the patient in MMF depending on the fixation and stability of the fractures, the comminution and complexity of the case, and the presence of an untreated condylar fracture.

4. Divide the face into upper and lower halves and stabilize them at the Le Fort I level

Divide the face into upper and lower halves (at the Le Fort I level) and begin either with the palate and MMF in the lower face unit or with the frontal bone in the upper facial unit proceeding to the NOE and zygoma.

Open reduction proceeds through each unit, and the two units are linked finally at the Le Fort I level.

5. Follow-up and potential complications

A panfacial fracture, in particular, should have good postoperative radiologic documentation of a proper reduction. Rescanning for assessing proper reduction should be considered depending on the nature of trauma.

Panfacial fracture patients need follow-up, which is appropriately coordinated by the CMF surgeon.

Dynamic forces (eg, masticatory function and occlusion), scarring, edema, sensory and motor dysfunction, atrophy, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction, dental problems, and late formation of mucoceles may contribute to unfavorable esthetic and functional outcomes with secondary deformities. In particular, malocclusion should be detected by frequent examination of the occlusion. Some cases are better managed by placing the patient in MMF for a period to ensure undisturbed healing.