Emergency treatment

Indications

Emergency treatment in midfacial fractures may be indicated in the following cases:

- Partial or complete visual loss due to direct or indirect optic nerve trauma

- Severely increased intraocular pressure

- Acute space-occupying lesion (eg, retrobulbar hematoma, emphysema)

- Severe shift of orbital content

- Entrapment of eye muscle (particularly in pediatric patients)

- Severe nasal or oral bleeding

- Full-thickness midface lacerations with open wounds (with and without severed branches of the facial nerve)

- Severed parotid duct (Stenson's duct)

Globe rupture and intraocular trauma

There are a variety of possible injuries affecting the globe that may require immediate ophthalmological treatment.

Retrobulbar hematoma

A pressure increase in the periorbital region due to retrobulbar hematoma can cause significant injury of the neurovascular structures with eventual loss of vision.

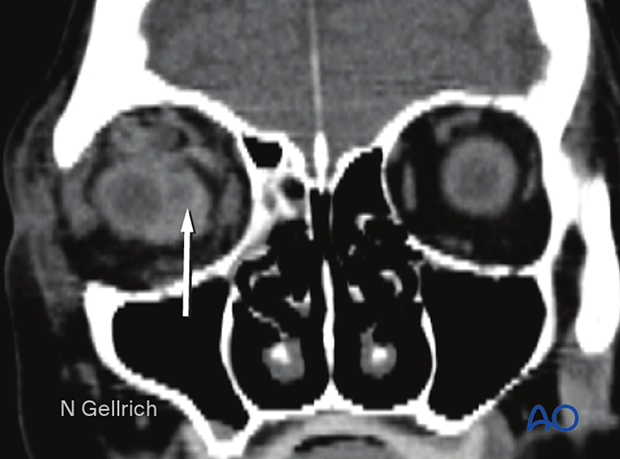

Coronal view, the arrow shows the collection of the blood (hematoma).

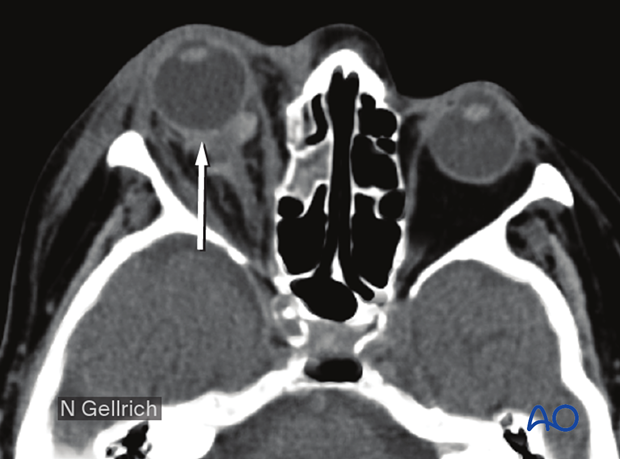

Axial view of the same patient, the arrow shows the collection of blood (retrobulbar hematoma) and proptosis of the right globe.

If a retrobulbar hematoma leads to a tense, proptotic globe, emergency decompression should be considered.

If a retrobulbar hematoma in a cooperative patient results in blindness, the time window to release the intraorbital pressure is limited to around one hour measured from the onset of blindness. This could mean urgent treatment under local anesthesia, even in the emergency room before further imaging. The standard treatment is a lateral canthotomy which may be accompanied by detaching the upper and lower lid attachment from the frontal process of the zygoma.

Transcutaneous transseptal incisions may help evacuate the hematoma and release the periorbital pressure. Transconjunctival pressure release can accompany the lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis.

An exception may be pulsating exophthalmos which may be a sign of carotid-cavernous sinus fistula. A fistula of this nature requires preoperative imaging of the neurovascular system, and the involvement of a neurosurgeon and an interventional radiologist.

Emphysema

Severe emphysema might significantly raise intraorbital pressure. If this compromises visual function or endangers the orbital contents, orbital decompression must be considered. Drug protocol may include antibiotics and decongestive nasal drops.

Patients with sinus fractures in the periorbital region should not finger-obstruct the nasal airway during nose blowing to avoid creating additional emphysema by blowing air into the orbit. Maintaining an open nose and mouth minimizes transmission of air into the orbit.

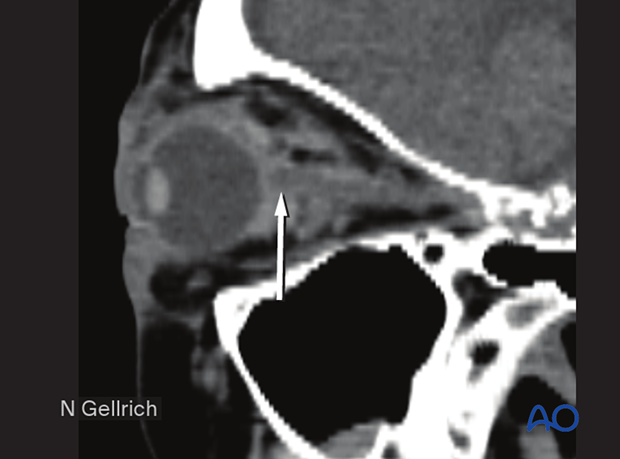

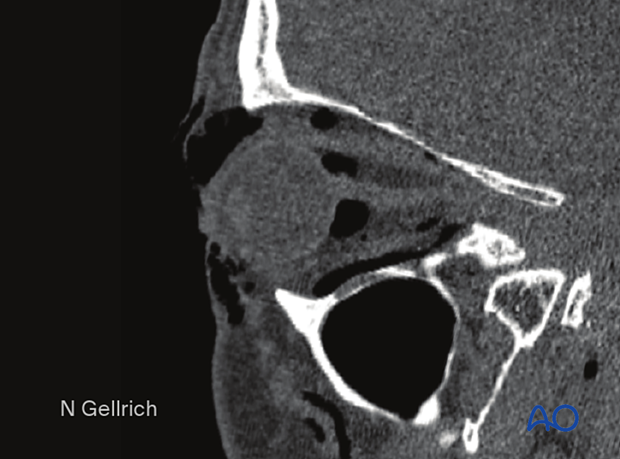

The sagittal image shows severe periorbital emphysema.

Entrapment of eye muscle (especially in children)

Usually, there is no need for emergency treatment in orbital floor/medial wall fractures unless there is visual compromise, hemorrhage, ie, retrobulbar hematoma, or displacement significant enough to compromise lid protection for the globe.

In some younger patients, the so-called trap-door phenomenon can occur, in which there is a danger of necrosis of the entrapped rectus muscle within a few hours, necessitating immediate release of entrapped tissues.

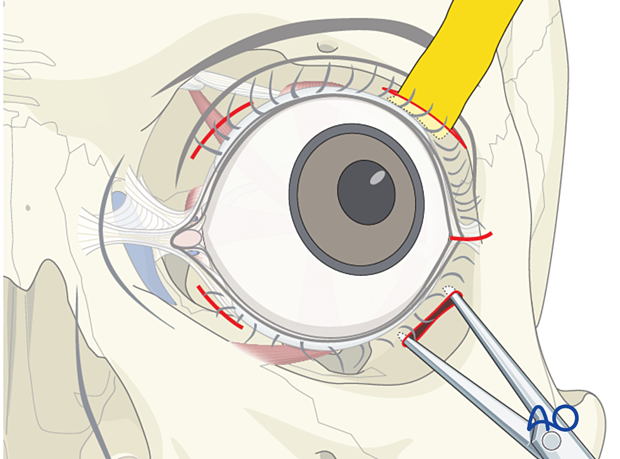

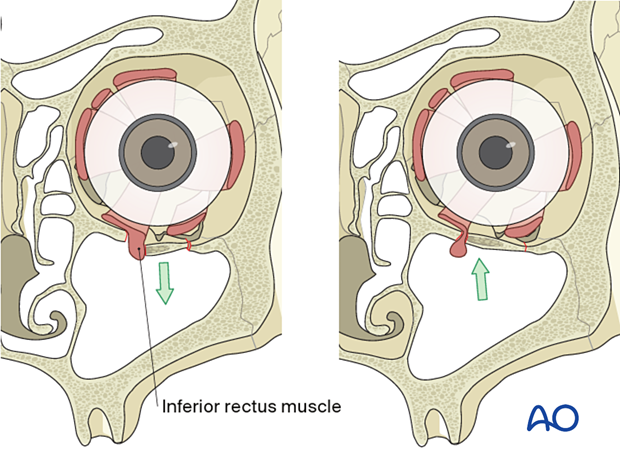

The inferior rectus muscle is the most common ocular muscle to become entrapped with an orbital floor fracture (trap-door phenomenon), and this may not be visible on conventional x-rays. Clinical examination provides evidence of significantly impaired ocular movement. Entrapment is often associated with severe ocular pain on attempted range of motion, as well as nausea and vomiting, especially in children.

A high-resolution CT scan is necessary to show the entrapment of the muscle. Entrapment requires urgent freeing of the incarcerated muscle to prevent necrosis.

The illustration shows the entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle (trap-door phenomena). Less commonly, in fractures of the medial orbital wall, the medial rectus muscle may become entrapped.

Bone fragments affecting the optic nerve

Special attention must be paid to the posterior third of the orbit and the bony optic canal. Bony dislocations in these anatomical areas are more likely to be associated with traumatic optic nerve lesions.

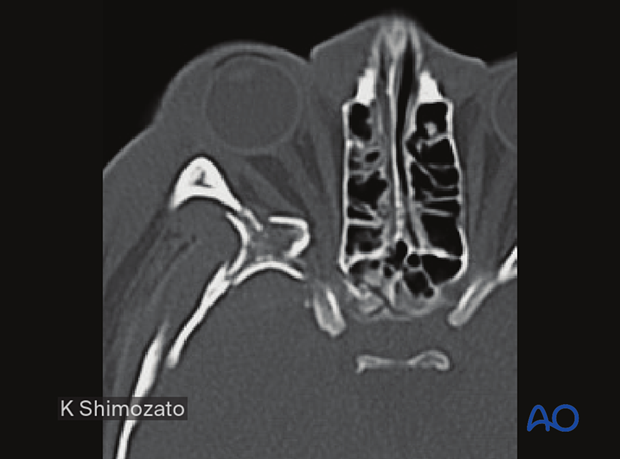

This axial CT scan in the plane of the optic nerve shows multiple fractures of the lateral orbital wall and the greater wing of the sphenoid of the right side. Stretching and compression of the right optic nerve are present. Fractures where fragments displace the posterior third of the orbit bones are associated with optic nerve impairment.

Severe bleeding

In case of severe bleeding, the following options should be considered:

- Assessment of current medical treatment for anticoagulation such as Coumadin, Aspirin, or other antiplatelet medication

- Compression by nasal packing, balloon tamponade, or direct compression

- Electrocautery if a clear bleeding source can be identified

- Control and adjustment of blood pressure

- Interventional embolization when other methods fail

- In some cases, fracture reduction may be required to reduce bleeding

- Intranasal inspection

- Angiography with possible super-selective interventional embolization