AOCMF Classification Midface (Level 1 and 2)

1. Introduction

Standardization and benchmarking of treatment options and potential outcomes in terms of quality of life have become a crucial issue within health care systems around the world due to the impact on cost-effectiveness and budgeting.

A universally acknowledged concept of agreed rules and definitions to describe fracture patterns within the craniofacial skeleton has become essential to ensure that like is compared with like in a classification scheme on a continuum from less severe to more and most severe.

The objective of the AO CMF classification for midface and orbital fractures is to provide standardized, validated recording charts as a basis for diagnosis, treatment decisions, surgical management, accurate data collection, and outcome evaluation.

The AO CMF fracture classification project has addressed the need of practitioners for guidelines in the daily care of individual patients and for database and evaluation purposes.

As with any classification, non-essential details were ignored, and certain aspects were left aside to emphasize general rather than individual features of a fracture pattern. This allowed the assignment of a particular fracture to a limited number of possible classes. This abstraction contrasts with fracture mapping in minute detail, which would necessitate copying imaging information into the recording forms.

From a long-term perspective, the categories and groups within the framework of a fracture classification must correlate to injury, severity, and the degree of difficulty of the treatment.

A prerequisite for quality control and establishing evidence-based treatment modalities is the achievement of adequate consistency, intra- and inter-observer reliability, and reproducibility in the initial documentation of trauma cases. A classification proposal requires pragmatic development through an iterative process of pilot and agreement studies under rigorous methodological surveillance and statistical validation.

Once potential problems and ambiguities which cannot be eliminated by a reconfiguration of the classification concept have been identified, these are outlined and illustrated in an instructional compendium. Instructions should facilitate uniform understanding and common language to eliminate misinterpretation.

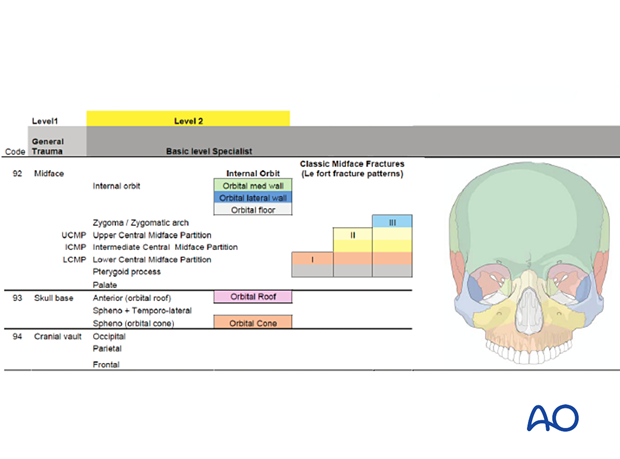

The fracture classification system is organized in four hierarchical levels:

Level 1: Elementary for general trauma assessment

Level 2: Basic for CMF specialty recording

Level 3: Focused modular/subunit CMF specialty recording

Level 4: Research coding

The levels are developed in a stepwise fashion. Levels 1 and 2 for the entire craniofacial skeleton are currently sufficiently complete to undergo validation studies in multi-center clinical settings.

While Levels 1 and 2 refer to the fracture localization, only Level 3 particularly focuses on the fracture morphology (fragmentation, the multiplicity of fractures, the severity of displacement, etc.) within location-specific modules such as the orbit, the anterior skull base, or the cranial vault. Each location-specific module has a similar concept. Level 4 is to be used in the context of future research projects.

The common denominator for the formal Level 1, 2, and 3 fracture classifications is the description of fracture topography, and its morphology based on the analysis of diagnostic x-rays, CT, or large volume cone beam imaging. Multi-plane imaging is advantageous and indispensable for the majority of fracture scenarios.

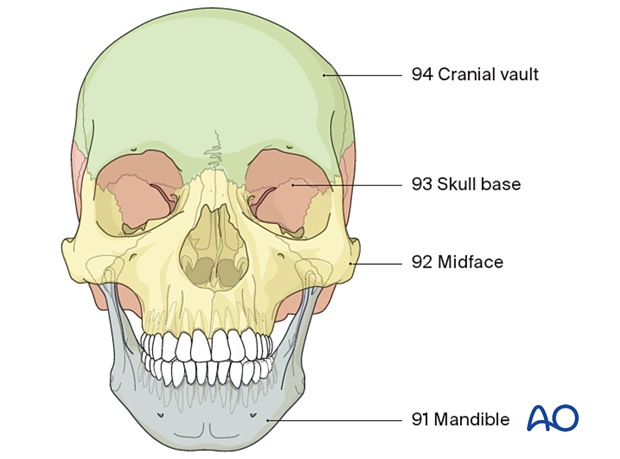

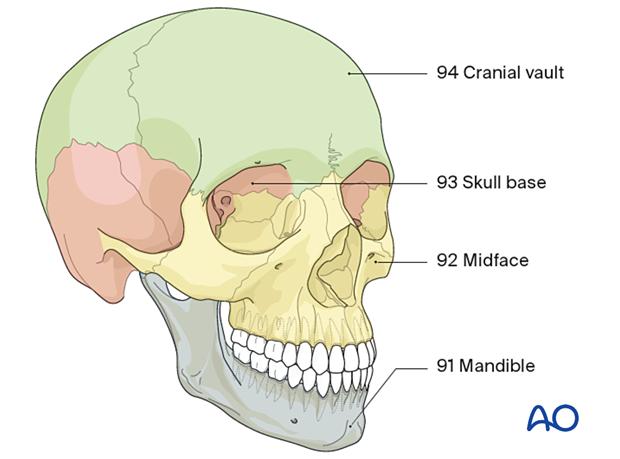

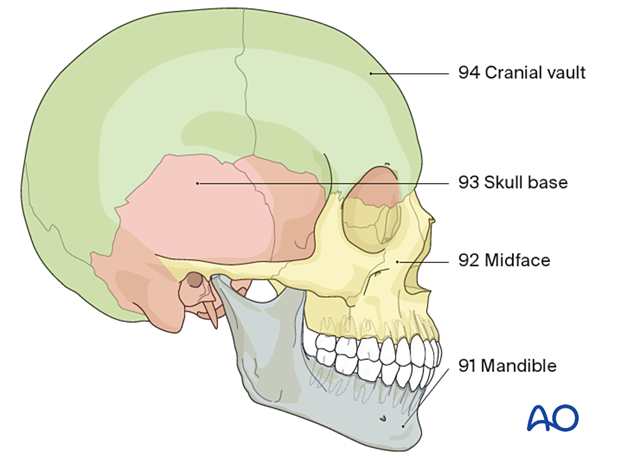

2. Level 1 - CMF fracture location

In Level 1, the fracture pattern is assigned to the following gross anatomic units:

- 91 = Mandible

- 92 = Midface

- 93 = Skull base

- 94 = Cranial vault

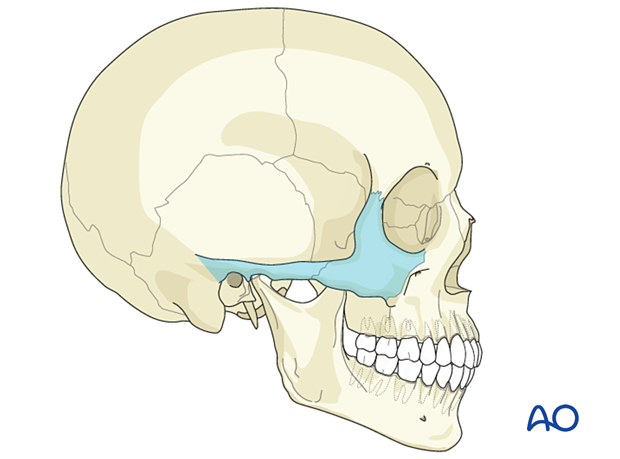

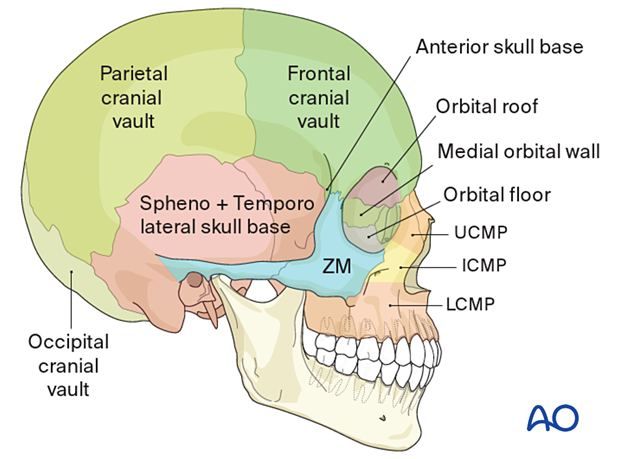

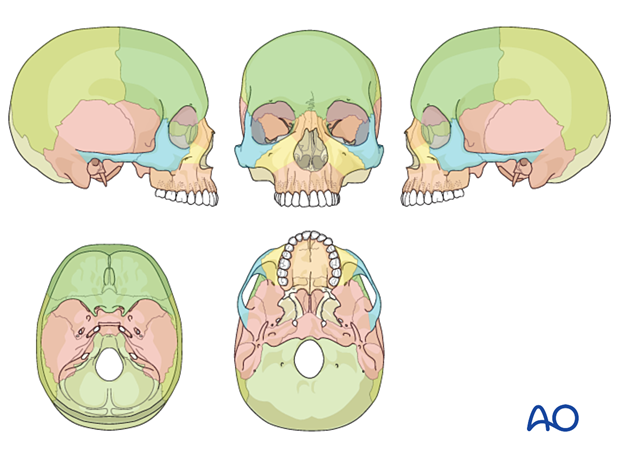

A three-quarter view of the facial skeleton showing the different anatomical subunits.

A lateral view of the facial skeleton showing the different anatomical subunits.

3. Level 2 - CMF fracture location

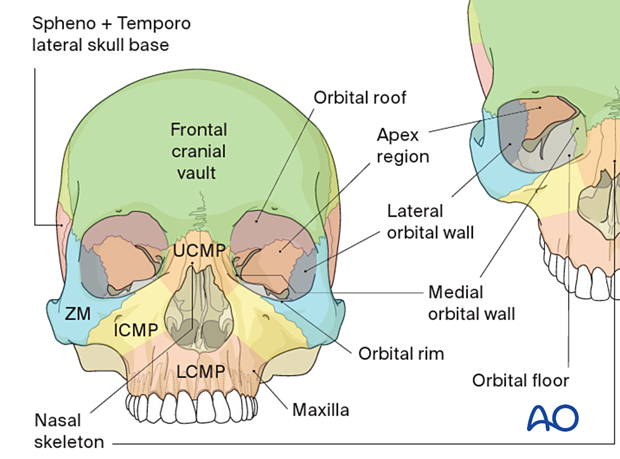

Level 2 describes topographic details of the gross anatomic units.

For the purpose of the AO CMF fracture classification, the midface is defined as the facial skeleton below the frontozygomatic, the frontomaxillary, and the frontonasal suture lines.

The midface consists of the following:

• Maxilla

• Nasal skeleton

• Zygoma (including the zygomatic arches along their entire length)

• Orbital rim

The internal orbit and the orbital walls are considered separate entities from the midface, and they are outlined in the section on the skull base.

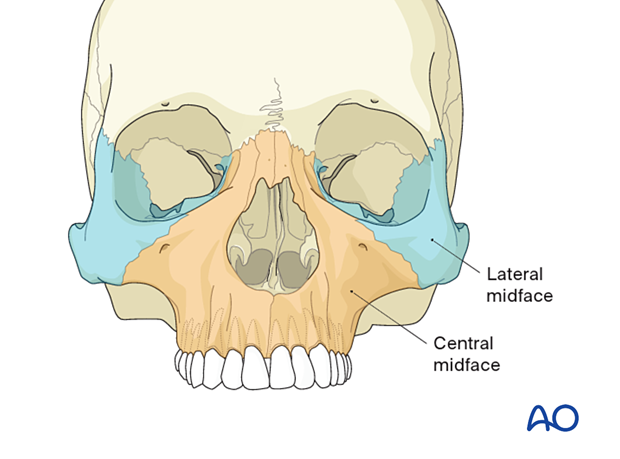

In terms of its vertical compartments, a central and a lateral portion of the midface can be distinguished.

4. Le Fort type midface fractures

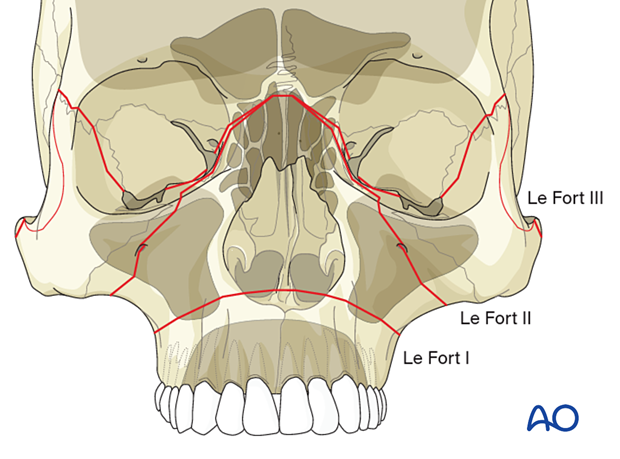

The simple distinction of three Le Fort midface fracture variants is the prototype for the classification of facial fractures.

The experimental cadaver studies of the French physician and pathologist René Le Fort date back to the beginning of the 20th century and led to an improved understanding of the major lines of weakness within the lattice-like bony architecture of the midfacial skeleton.

Though the predictable course of the resulting low-energy fracture lines does not entirely replicate the often high-energy, complex midfacial injury patterns seen today, the Le Fort scheme is undeniably popular among the medical community.

The non-verbal visual logic of the Le Fort scheme represents an ideal worthy of integration into any new midface fracture classification, such as the Level 2 AO CMF.

Furthermore, the comprehensive cartographic assembly of the Level 2 AO CMF fracture classification includes fracture pattern scenarios beyond the three Le Fort variants: regional comminution, the inclusion of multiple skeletal units, extension into the skull base, or involvement of the mandible.

5. Maxillae, central midface, and partitions

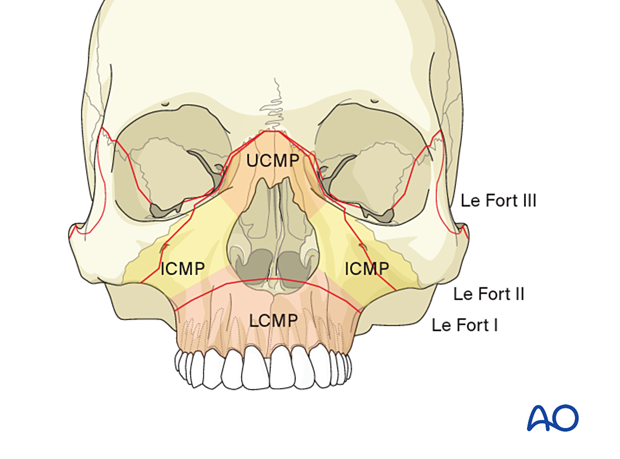

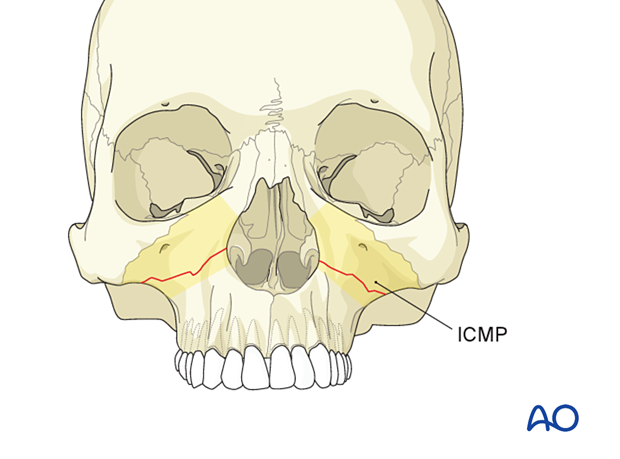

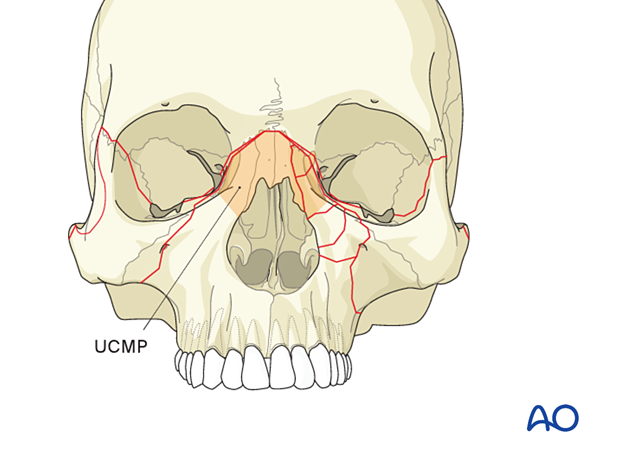

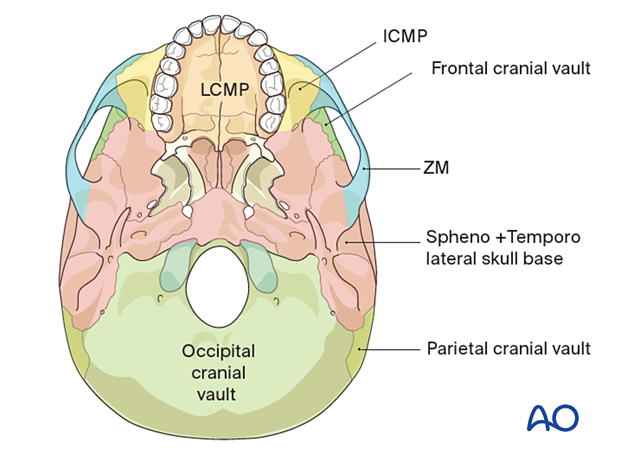

The Level 2 AO CMF fracture classification is tailored to delineate Le Fort fracture levels with the help of three virtual horizontal partitions, stacked one upon the other along the vertical nasomaxillary buttresses of the central midface:

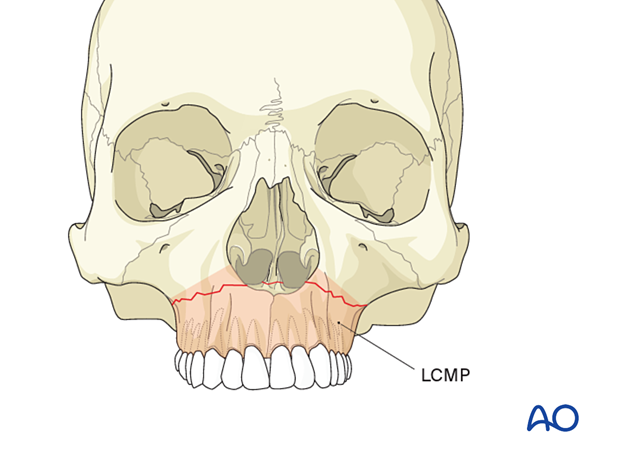

- LCMP = Lower Central Midface Partition

- ICMP = Intermediate Central Midface Partition

- UCMP = Upper Central Midface Partition

The anterosuperior borderline of the LCMP corresponds to the Le Fort I fracture level and runs from the most lateral point of the piriform aperture to the foot of the zygomatic crest.

The ICMP consists of the infraorbital portion of the maxilla constituting the facial wall of the maxillary antrum. The ICMP is caudal to a line connecting the entry point of the nasomaxillary suture and the lateral margin of the lacrimal fossa.

So-called high Le Fort I fractures or transverse midface fractures that do not include the nasal skeleton spread across the ICMP.

The Upper Central Midface Partition boundaries correspond to the bony nasal skeleton consisting of the upper ends of the frontomaxillary processes and the nasal bones between.

Le Fort II, Le Fort III, nasal, and all variants of NOE fractures involve the UCMP.

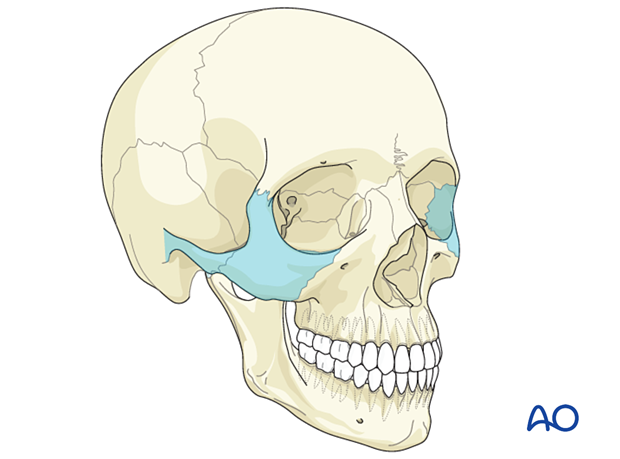

6. Lateral midface - zygoma

The lateral midface is regarded as a single unit composed of the zygoma and the zygomatic arch.

In the classification chart, the zygomatic arch reaches posteriorly to the temporal bony base of the glenoid fossa without the involvement of the zygomaticotemporal suture line.

The orbital surface of the zygoma (lateral orbital flange), however, is an element of the lateral orbital wall and recorded as such.

The lateral midface may be involved in isolated fractures of the zygomaticoorbital complex as a subcomponent of a Le Fort III fracture.

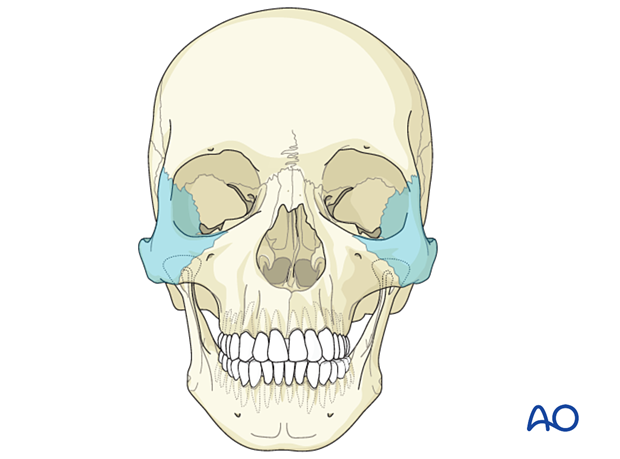

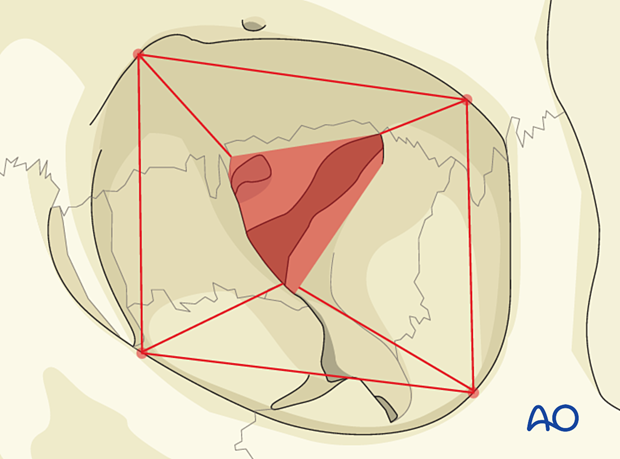

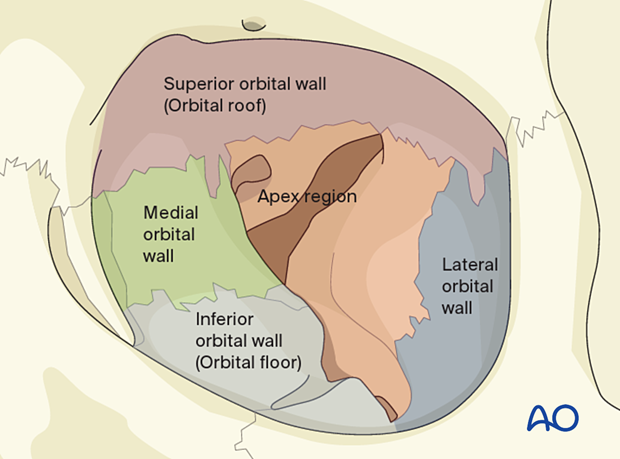

7. Internal orbit - orbital walls

The internal orbit and the orbital walls are located within the transition between the facial skeleton and the cranium. The posterior third (apex or cone) and the roof of the orbital cavities are part of the skull base, whereas the medio-inferolateral portions of the midorbit and anterior third belong to the face.

Independent of their anatomic composition (an assembly of seven different bones), the internal orbits are displayed within the Level 2 AO CMF fracture classification according to the geometric concept of a pyramid with a quadrangular base. Towards its apex, the orbit converges into a three-sided conical shape.

Thus, from the beginning of the apex, four walls are distinguished:

- Inferior orbital wall or orbital floor

- Medial orbital wall

- Lateral orbital wall

- Superior orbital wall or orbital roof

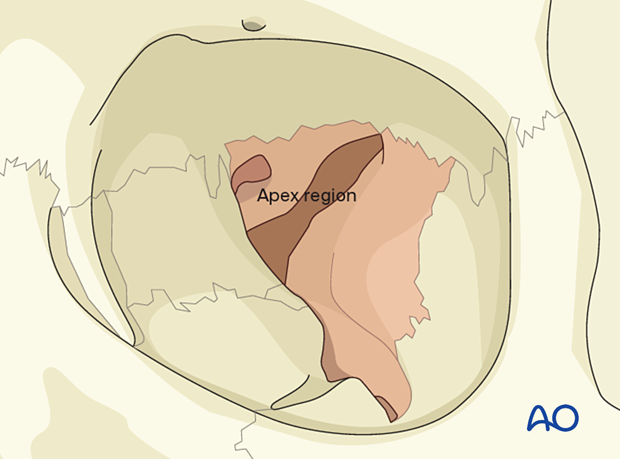

8. Internal orbit - apex region

The orbital apex is regarded as a separate unit, though consisting entirely of the sphenoid and its wings.

A landmark to define the entry point into the apex is the posterior extent of the inferior orbital fissure.

9. Skull base and cranial vault

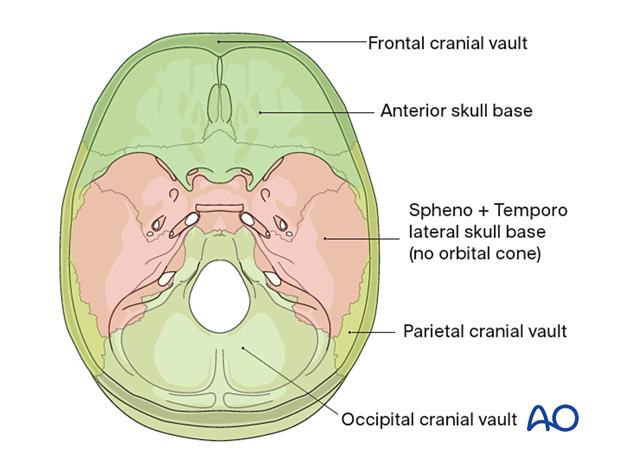

For the sake of completeness, the Level 2 AO CMF fracture classification charts of the skull base and cranial vault are presented here.

The recording charts refer to the skull base in a simplistic manner.

Regarding the cranial fossae, three major divisions are defined:

- Anterior skull base (related to the anterior cranial fossa)

- Spheno- and temporolateral skull base

- Occipital cranial vault (related to the posterior cranial fossa)

Each of these divisions comprises several bone components. If a fracture occurs in any such regional component, the whole division is considered to be involved.

The anterior skull base primarily consists of the frontal bone, ie, the orbital roofs, the cribriform plate, and the jugum, as well as the lesser wings of the sphenoid. The squamous part of the frontal bone is designated as the frontal cranial vault. Frontal sinus fractures are all regarded as fractures of the frontal cranial vault.

The spheno-temporolateral skull base comprises the sphenoid body, the greater sphenoid wings, the temporal bone, and the groove for the sigmoid sinus.

The occipital cranial vault includes the posterior skull base and is designated as such.

The basal view shows the extent of two of the three major divisions of the skull base:

- Spheno- and temporolateral skull base

- Occipital cranial vault

The facial substructures formed by the zygomas and the maxillae conceal the anterior skull base from view.

Though anatomically speaking the pterygoid processes are part of the sphenoid, they are considered distinct elements in the definition of a classic Le Fort fracture, where involvement is mandatory.

10. Fractures of midface and orbit - Level 2 diagrammatic recording

As in the Le Fort classification, the current AO CMF classification Level 1 and 2 address fracture localization only.

In a graphical scheme of the skull, diagrammatic recording of the fracture pattern in the midface, orbits, skull base, and the cranial vault is done by checking criteria in the appropriate subdivision.

11. Fractures of midface and orbit - Level 2 spreadsheet-style recording

Another option is documentation in the style of a spreadsheet.

The spreadsheet boxes are color-coded in the same way as the anatomical divisions or partitions of the skull.

Checking the boxes reveals the relevant Le Fort pattern as a summary.

12. Midface and internal orbit Level 3 - fracture morphology

The fracture morphology refers to the fragmentation (number of fragments and fracture lines) and the displacement.

Many descriptors and terms for classification and grading of the fracture severity are considered in this level such as:

- Single versus multiple

- Simple versus complex/multifragmentary

- Open versus closed fractures

- Displaced versus non-displaced

- Mobile versus non-mobile

Fracture displacement can often be deduced from imaging. Fracture mobility is actually a clinical descriptor. The clinician uses his hands to feel for the mobility of the fragments.