Airway considerations

1. Introduction

The establishment and maintenance of a patient airway is always the highest priority through all phases of pre-hospital and hospital care. Its management includes assessing, establishing, and protecting the airway along with appropriate oxygenation, humidification, and ventilation.

The need for emergency management may arise at any time during patient care.

Foreign body

Unstable teeth, artificial implants, or dentures need to be addressed. A preoperative treatment must be performed to remove any objects obstructing the airway.

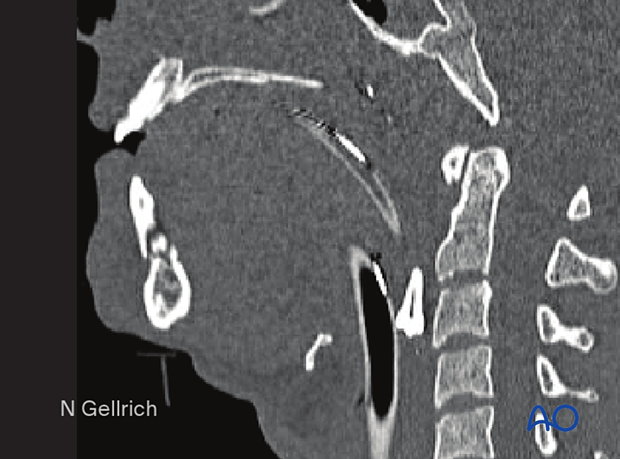

X-ray examination (neck, chest, and abdomen) must be performed when there is doubt regarding the integrity of the dentition or suspicion that other objects are missing and unaccounted for.

This radiograph shows a tooth in the pharynx.

Preoperative treatment

Procedures to consider during primary care of CMF trauma patients:

- Suction

- Clearing the airway of foreign debris (dentures, loose teeth, etc.)

- Tongue positioning/retraction

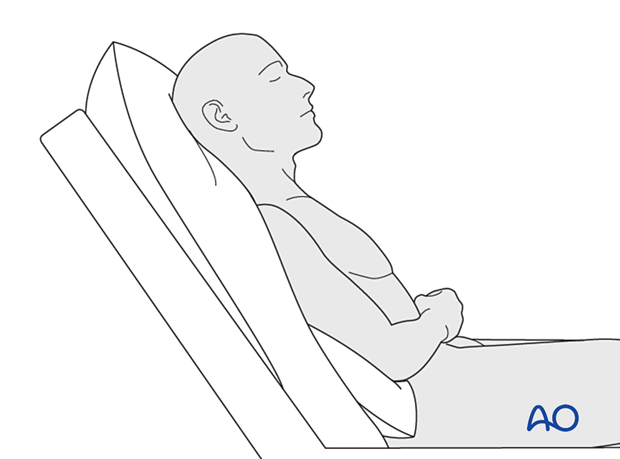

- Patient positioning

- Use of appropriate temporary airway devices

- Temporary stabilization of fractures

- Tracheotomy

Operative treatment

During surgery, airway management must be appropriate for the patient and should allow the surgeon adequate operative access.

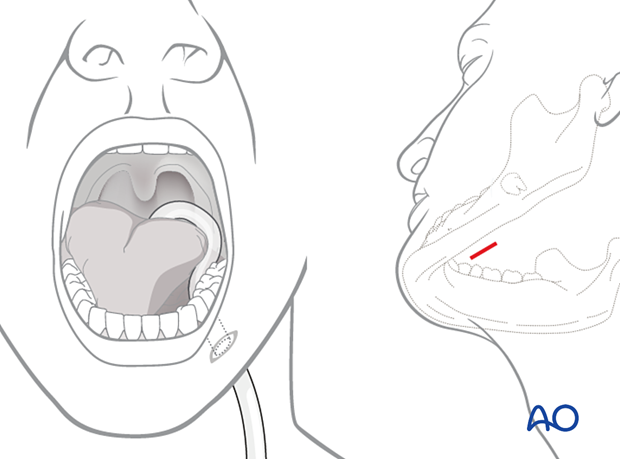

Several approaches can be considered for an endotracheal tube, such as nasoendotracheal, oral endotracheal, or submental/submandibular intubation.

Airway management technique may also depend on the need for prolonged postoperative stabilization, such as MMF, stability in the case of severe swelling, or a compromised level of consciousness. In such cases control of the airway is achieved with an indwelling endotracheal tube or tracheostomy.

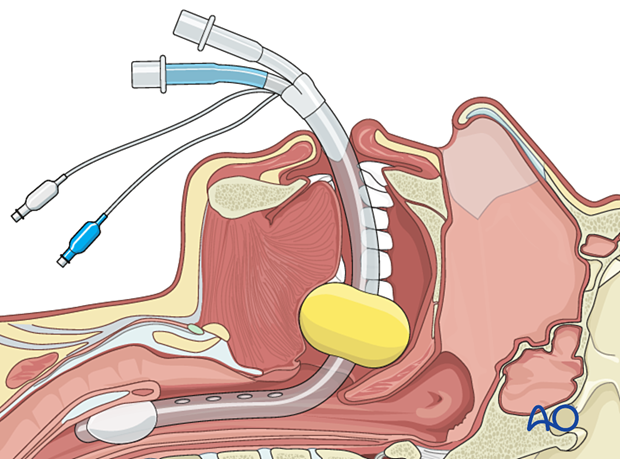

A throat pack is used during the surgery and removed at the end of the procedure.

Furthermore, gastric decompression at the end of the procedure is also recommended. This is accomplished by the placement of a nasogastric tube which may be left in place for postoperative care.

Postoperative treatment

Procedures to consider during postoperative care of CMF trauma patients:

- Suction

- Supplemental oxygenation with humidification (nasal prongs, masks, etc.)

- Patient positioning

- Use of appropriate airway devices

- Methods to reduce swelling including head elevation, nasal decongestants, possible use of steroids, cold packs

2. Airway devices

The airway can be compromised from bleeding, swelling, foreign bodies, or altered mental state.

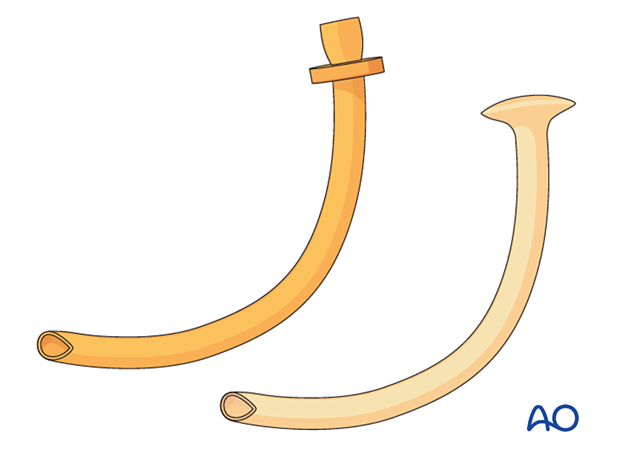

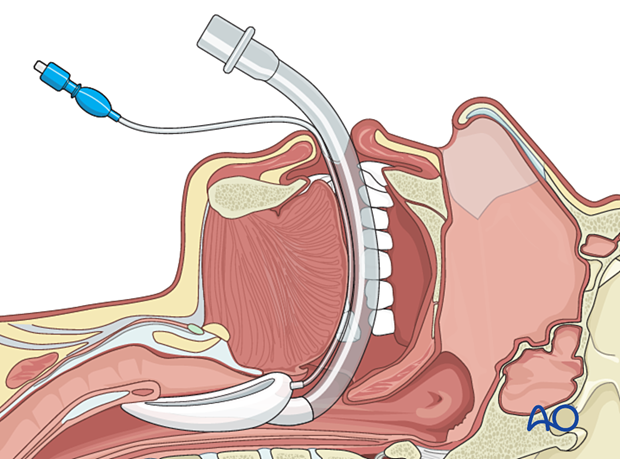

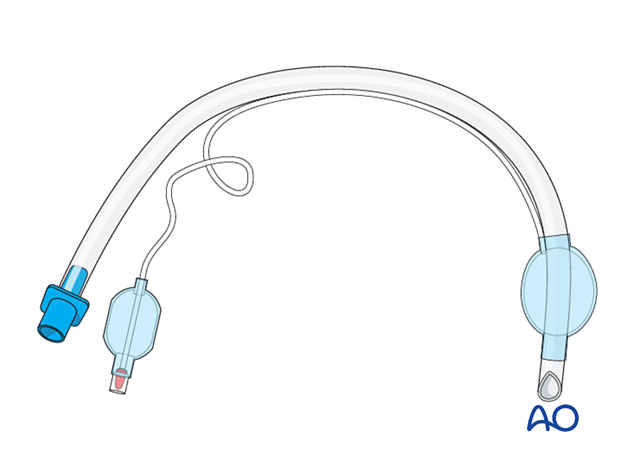

Various devices are available to help establish the airway on a temporary or permanent basis. These include a nasopharyngeal airway device, shown here.

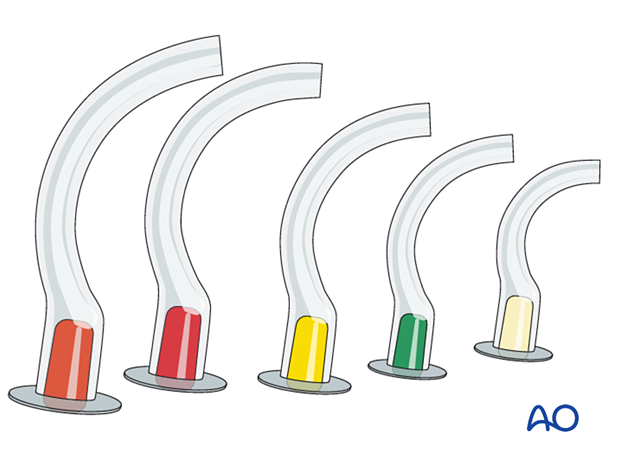

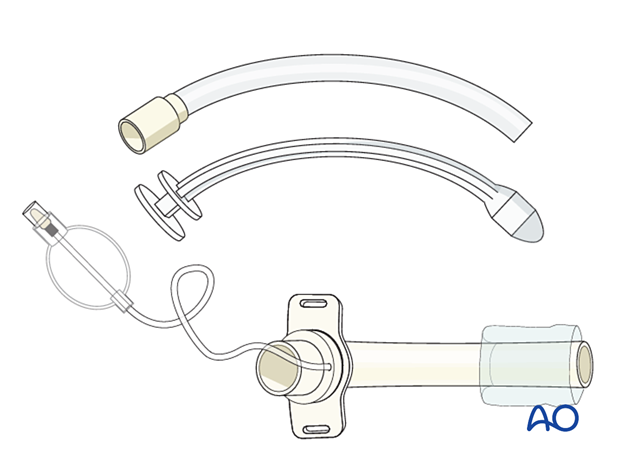

This illustration shows an oropharyngeal airway device (Guedel airway).

Some devices are helpful in cases of emergency to establish a secure airway, such as a Combitube (esophageal tracheal airway), shown here.

This illustration shows a Fastrach.

This illustration shows a laryngeal mask.

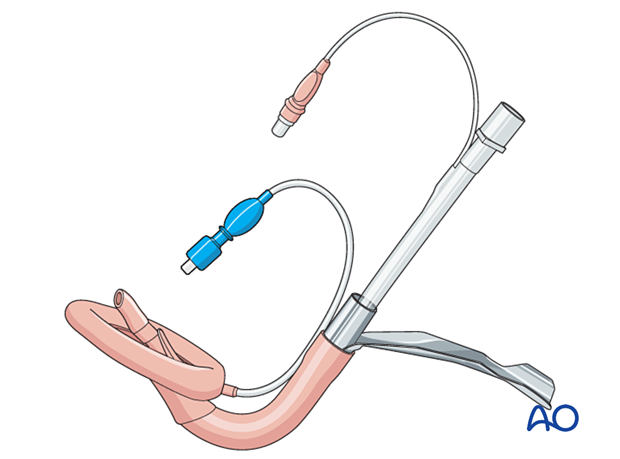

This illustration shows a cuffed nasoendotracheal tube.

This illustration shows a cuffed tracheostomy tube.

3. Swelling

Nasal cavity swelling

After a midface injury, particularly a Le Fort fracture, and surgery there is significant mucosal swelling. Postoperatively, the use of antihistamine medication, vasoconstrictor nasal drops, saline nasal mist, or general steroid medications may be helpful, as is head elevation following surgery.

The nasoendotracheal tube may be left in place after surgery and during intensive care as required until edema and level of consciousness have improved.

Tongue edema/swelling

Severe edema of the tongue may obstruct the airway.

In mild cases, a nasopharyngeal airway device may be sufficient, but intubation and/or a tracheotomy are more secure and are preferred for severe cases.

Pharyngeal swelling

Severe facial injury often results in pharyngeal swelling. Edema may result in swallowing dysfunction. Airway narrowing is the result of mucosal, lingual, and pharyngeal swelling.

In mild cases, a postoperative nasopharyngeal airway device may be utilized but a tracheostomy or intubation provides a secure airway, especially in the case of increasing swelling or if the patient is in MMF.

In some cases, the surgeon may choose to leave the arch bars on and remove the MMF (elastics or MMF wires) for the first few days postoperatively until the facial edema has improved. Once the patient is more awake and the airway is better protected, MMF may be reinstituted.

4. Bleeding

Bleeding presents a severe risk to the airway. It may compromise the airway or fill the stomach, increasing the risk of vomiting and/or aspiration. Increased risk of aspiration exists in patients with an altered level of consciousness.

It is important to diagnose the cause of bleeding and control it. A gastric tube may be used to decompress the stomach and reduce the risk of vomiting and aspiration.

If massive bleeding continues, it may be necessary to place an endotracheal airway.

Hemostasis may be obtained with:

- Control of blood pressure

- Vasoconstrictor based nasal decongestants

- Injection of vasoconstrictors

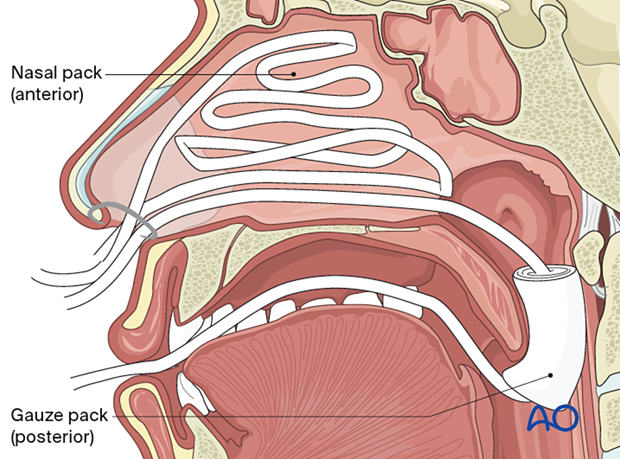

- Anterior or posterior nasal packing

- Cauterization

- Selective embolization

Nasal bleeding

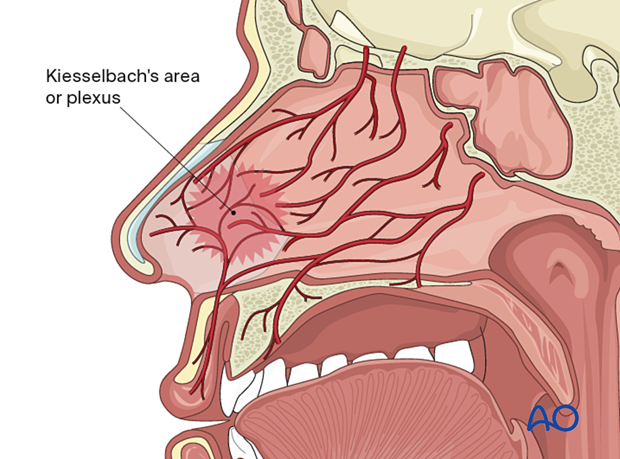

In a non-trauma patient, a common location for nasal bleeding is Kiesselbach’s plexus. The surgeon must be aware that nasal bleeding following trauma may be from many other locations, including the skull base.

Massive bleeding is usually controlled by head elevation, ice packs, tamponade using nasal packing, or a balloon device. If massive bleeding is not controlled by tamponade, the patient should be taken to radiology where angiography identifies, and selective embolization of the injured vessel controls the area of hemorrhage. Bleeding from lacerations or wounds may require control in an operating room setting.

Initial attempts to control nasal/pharyngeal hemorrhage are made with anterior and posterior nasal packing (ie, Bellocq tamponade, the balloon of a Foley catheter, or other balloon devices specifically designed for nasal tamponade). Proper positioning of packing is essential.

5. Laryngeal fracture and trauma

Laryngeal trauma is often overlooked and should be considered in any patient who has sustained severe facial trauma, especially blunt injury to the midneck.

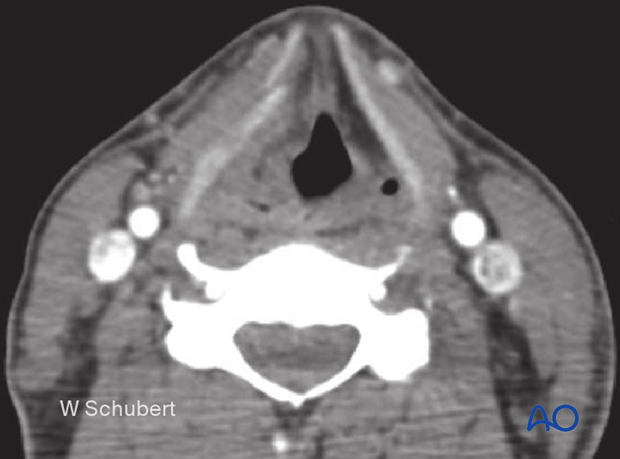

Laryngeal trauma should be suspected in any patient with pain, swelling, ecchymosis, or subcutaneous emphysema over the laryngeal area. It is seldom the main complaint and is often a subtle physical finding relative to other obvious injuries to the face. Air within the tissues may be noticed on CT examination.

Laryngeal trauma commonly occurs from blunt trauma to the larynx. It can also be seen in patients following an event of blunt injury to the neck, strangulation, or attempted hanging.

It may or may not be associated with a laryngeal fracture.

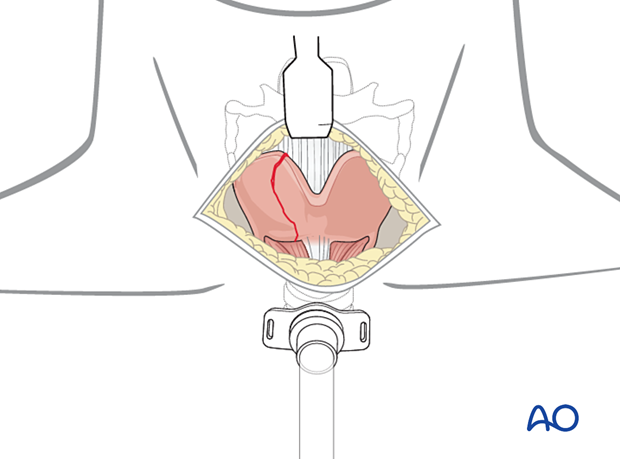

This case example shows a laryngeal fracture on the right side.

The patient may present with an inadequate airway. The injury may be associated with a laryngeal hematoma, making intubation difficult or impossible. An emergency cricothyroidotomy/coniotomy is then indicated. One risk of cricothyroidotomy/coniotomy is that the procedure is often performed through the zone of injury and of severe swelling and hematoma, resulting in significant bleeding and complete loss of the airway. Therefore, most surgeons would recommend a tracheotomy (establishing the airway inferior to the zone of injury and swelling) rather than an emergency cricothyroidotomy/coniotomy if a significant laryngeal fracture is suspected.

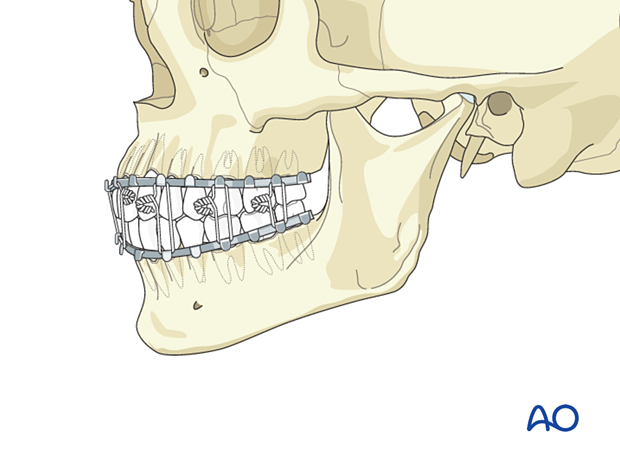

6. Mandibulomaxillary fixation (MMF)

The airway may be compromised in patients in maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). In addition to this, vomiting or a low Glasgow coma score (GCS) can result in further airway problems or inadequate ventilation. To solve this problem, should it occur, the MMF can be released, and a better airway established such as with a tracheostomy. For patients at risk, adequate internal fixation may obviate the need for MMF, allowing unobstructed respiration through the mouth.

7. Intubation

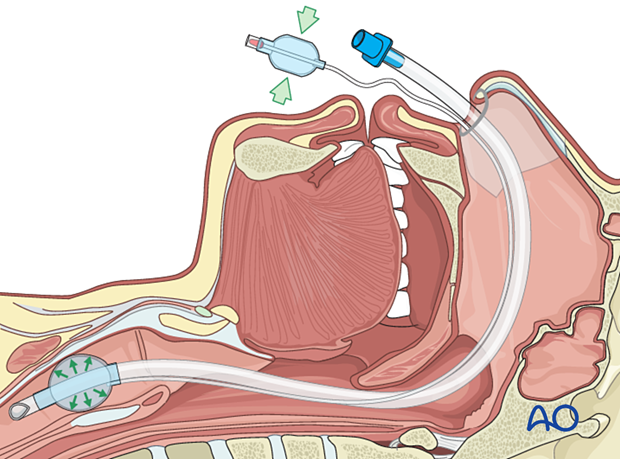

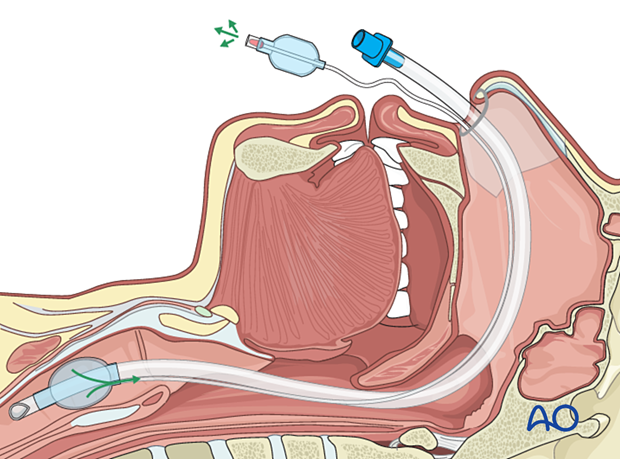

Nasotracheal intubation

During operationThe tube is inserted into the trachea and, once it is in place, the cuff is adequately inflated to seal the trachea. The tube needs to be fixed in place. This can be done by suturing to the nasal septum (recommended in fracture repair) or taping it to the nose and cheek area.

If the patient must remain intubated postoperatively, the cuff is released and inflated intermittently every 2–3 hours to prevent pressure necrosis of the mucosa lining the trachea.

In this mode frequent suctioning is necessary to prevent salivary aspiration.

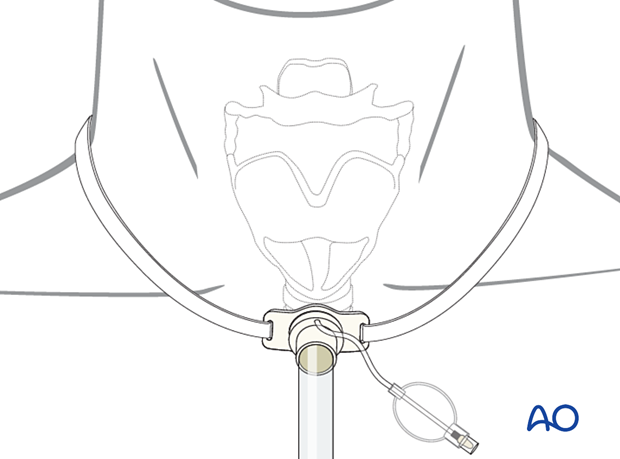

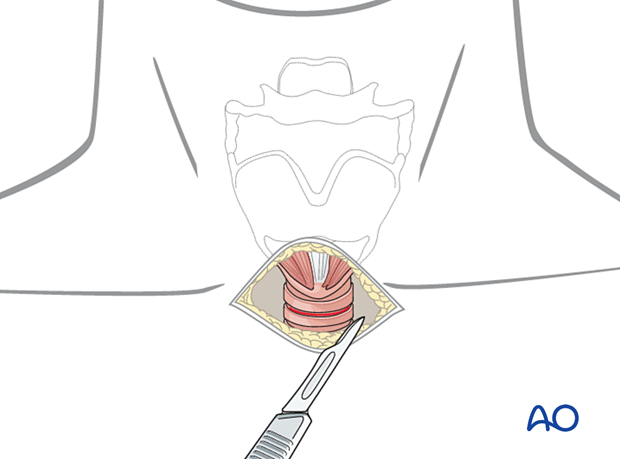

Tracheotomy

In some cases, a tracheotomy may be necessary.

A cannula is inserted into the trachea and stabilized with a tracheostomy tie and suture.

The secretions must be suctioned frequently. Proper skincare is also essential.