Use of existing lacerations

1. Principles

General considerations

Facial fractures are often associated with lacerations. These existing soft-tissue injuries can be used to access directly the facial bones for management of the fractures.

The surgeon may elect to extend the laceration to attain enough access to the fractured area, placing additional incisions starting from the wound margins along the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL).

Bacterial contamination is not a contraindication for the use of existing lacerations for surgical approach.

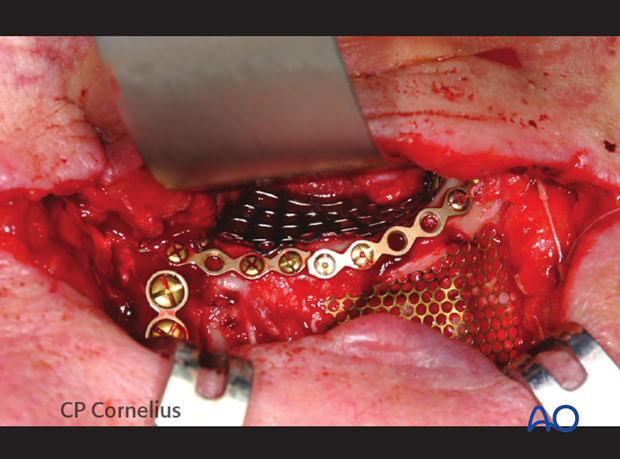

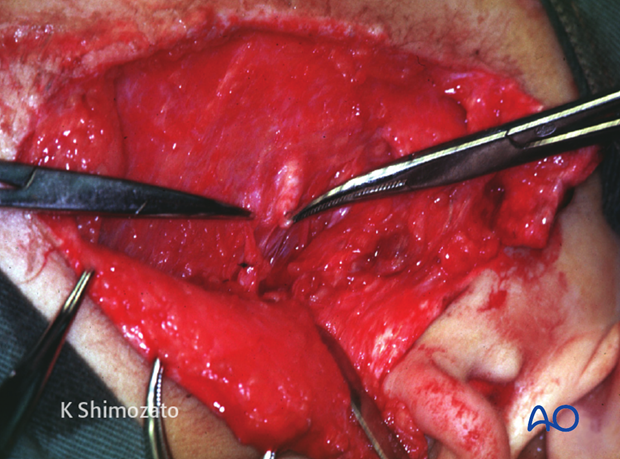

Access to infraorbital rim and orbital floor through a horizontal lower lid laceration is shown.

Clinical photograph of the same case showing osteosynthesis and orbital mesh plate applied through the existing laceration.

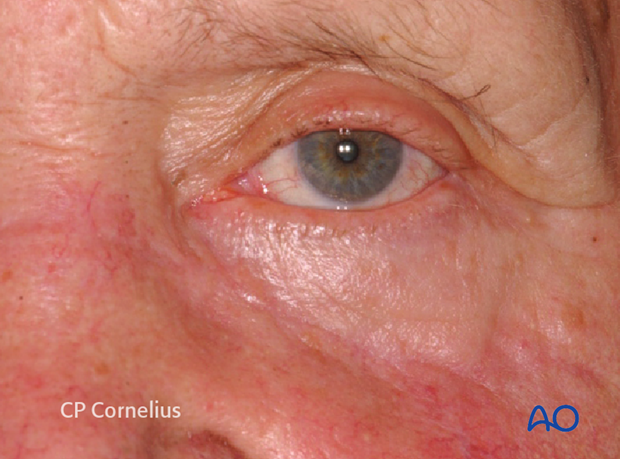

This photograph shows an acceptable outcome after using the laceration for surgical approach.

Peripheral nerve and parotid duct injuries

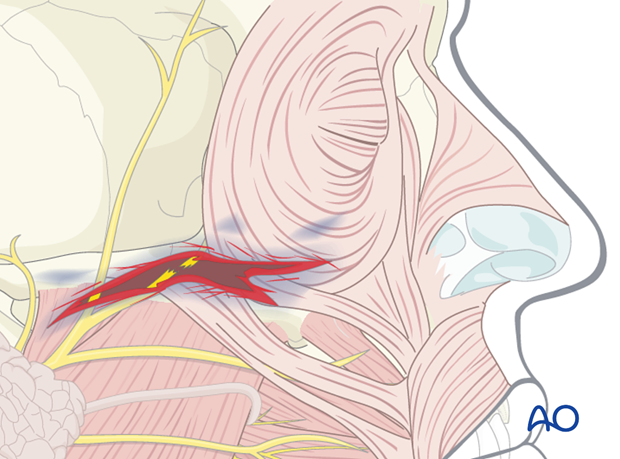

Depending on the location of the laceration, structures such as nerves, the parotid gland, or the parotid duct may be affected by the injury.

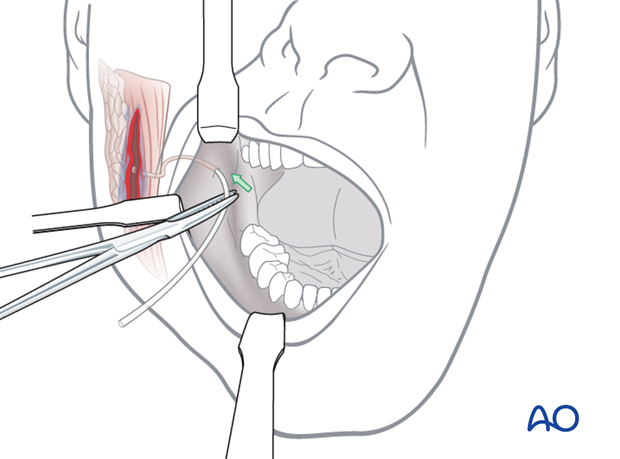

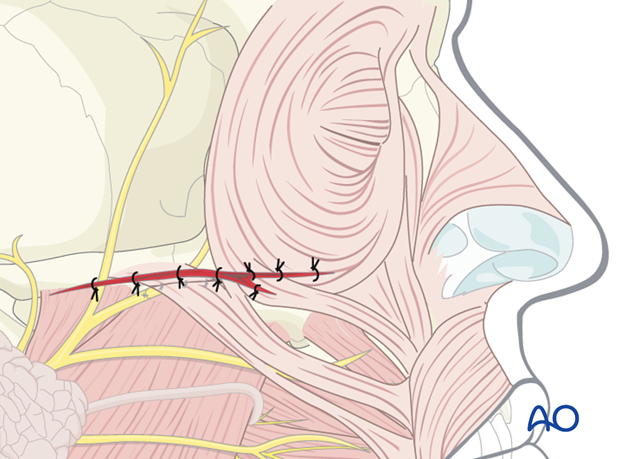

In the illustration, a peripheral facial nerve branch is directly involved. Respecting their functional importance the facial nerve branches can either be repaired primarily or tagged for ease of location during a secondary repair. Aggressive exploration and primary repair under microscopic magnification is advantageous at least for the branches responsible for lid closure.

Parotid duct injury and repair

Injuries of the parotid duct may cause an acute leakage of saliva into the wound or surgical field resulting in salivary fistula.

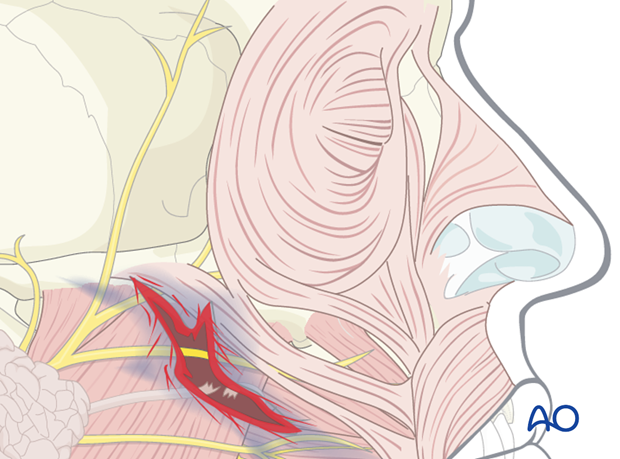

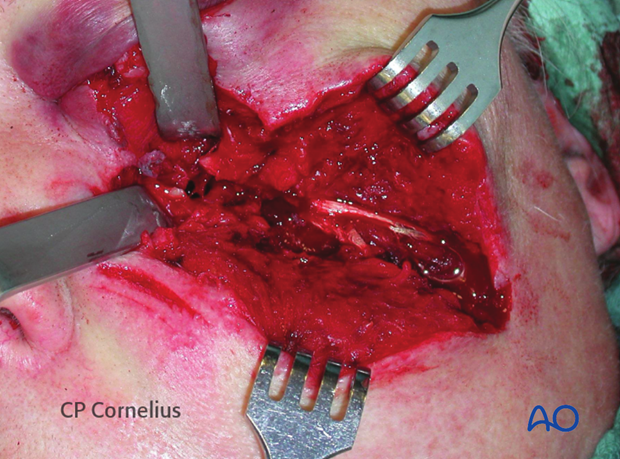

The parotid duct ends can be explored through the laceration in such cases.

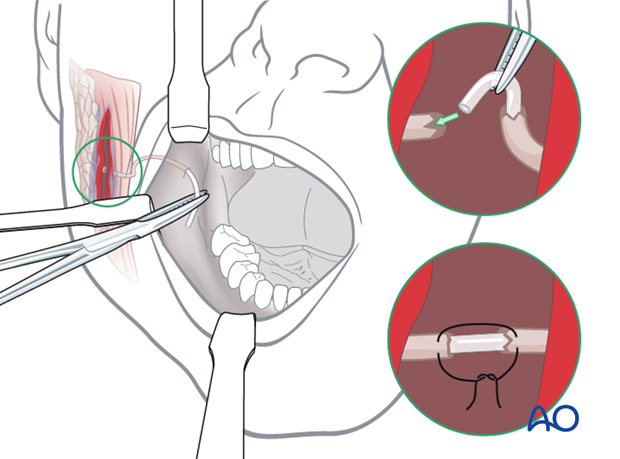

Repair of the parotid duct

The distal portion of the duct is entered from the intraoral orifice and stented with silastic tubing until continuity is reached with the lumen of the proximal duct.

The edges of the duct are reapproximated and closed over the stent using microsurgical instrumentation. The silastic tubing is left in position for a period of up to 3 weeks.

Unrepaired parotid duct injuries result in a persistent fistula or sialocele.

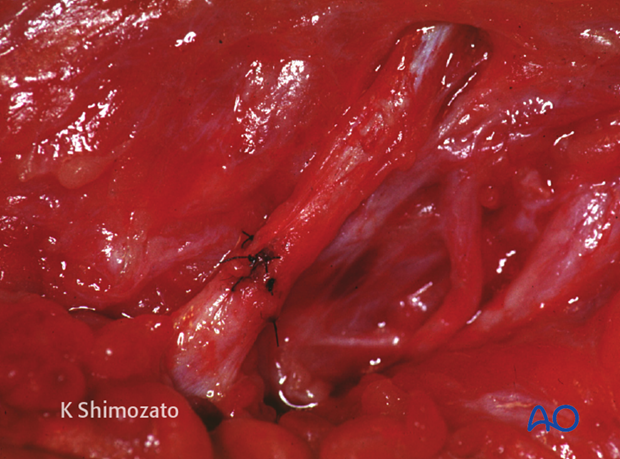

This clinical photograph shows a repaired parotid duct.

2. Wound closure

Proper cleansing, debridement, and hemostasis should be accomplished prior to the repair of the underlying bony injury, cranial peripheral nerve injuries, or an injured Stensen’s duct (parotid duct).

Facial wounds can be closed primarily up to 24 hours after the injury due the high vascularization of this region.

The laceration is closed in layers with short-term resorbable interrupted sutures, realigning the anatomic structures and eliminating dead space:

- Periosteum

- Mimetic muscles

- Platysma/SMAS

- Subcutaneous tissues

- Epidermis

Particular attention is given to completing the repair of free eyelid margins, nasal alae, the vermilion lip borders and the helical margins of the ear.

A variety of skin closure techniques are available based on surgical preference. A drain may be placed if necessary.

Usually the wound is not covered with dressings

A pressure dressing, however, serves to flatten large soft tissue avulsions and avoid contour deformities by scar contraction.

3. Example of a facial laceration with underlying fracture

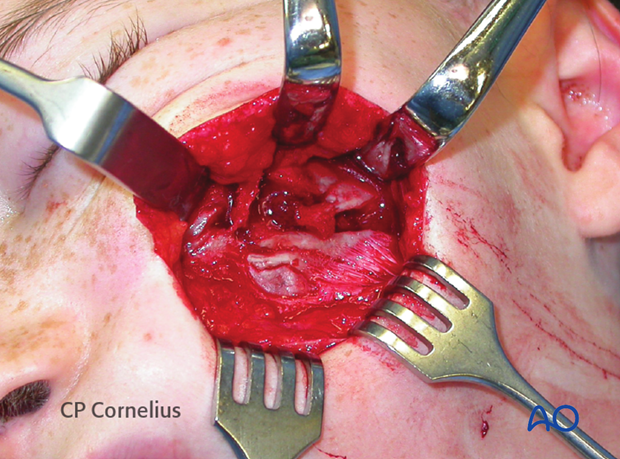

This image shows an example of soft-tissue laceration after a horse-shoe injury.

Elevating the soft-tissues reveals an underlying multifragmentary zygoma fracture.

This image shows an example of soft-tissue laceration after a chain saw injury.

Elevating the soft-tissues reveals an underlying multifragmentary fracture of the infraorbital rim and the orbital floor.

4. Postoperative care and follow-up

Close monitoring of the early wound healing phase is necessary in order to detect infection early enough to prevent wound slough and abscess formation.

Remove sutures in an appropriate time frame.

Instruct the patient to avoid sun exposure and use protection such as hats, shields and sunscreen.

Further interventions may help to minimize scar contractures and hypertrophy.

Remind the patient that facial scars need months to mature, lose their redness and become less conspicuous.