Terminology

1. Introduction

Six descriptors are commonly used to describe and categorize fractures:

- Location

- Complete versus incomplete

- Fracture morphology

- Open/compound/contaminated versus closed/noncompound/non-contaminated

- Displaced versus nondisplaced

- Mobile versus nonmobile

2. Fracture location

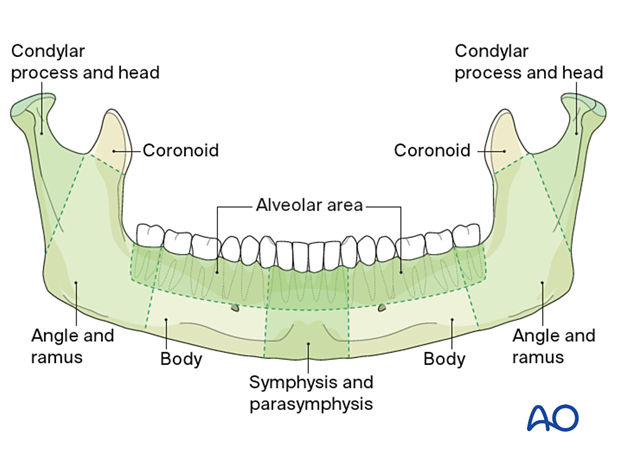

Most clinicians generally subdivide the mandible into the following anatomic locations:

- Symphysis and parasymphysis

- Body

- Angle and ramus

- Condylar process and head

- Coronoid process

- Alveolar area

Multiple fractures are those involving more than one anatomical location of the mandible.

3. Condylar fractures

General considerations

Controversy has surrounded all aspects of fractures of the condylar process. There have been several proposed classification methods of these types of fractures.

The AO classification is presented below, along with a simplified version. The AO classification allows for better communication between radiologists and surgeons. On the other hand, the simplified version better reflects the clinical treatment implications.

AO Classification

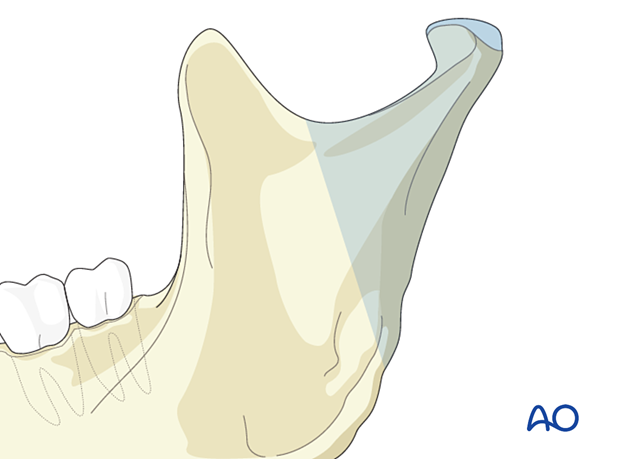

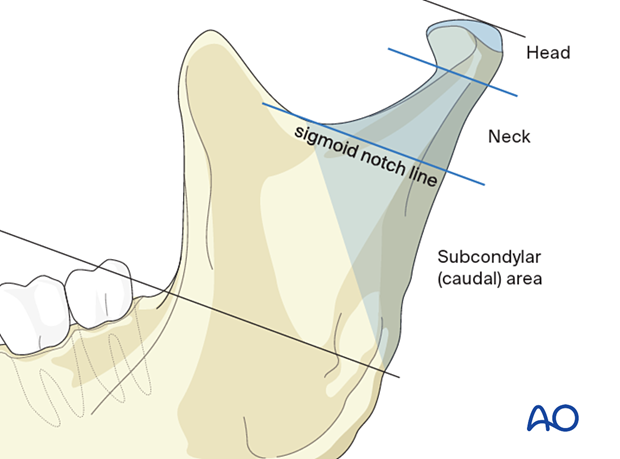

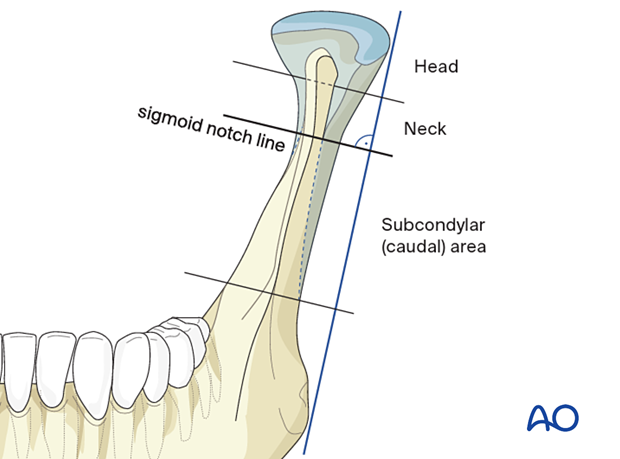

The condylar process and head is a subunit of the mandible and is defined by an oblique line running backward from the sigmoid notch to the upper masseteric tuberosity. The condylar process is divided into three subregions:

- Head

- Neck

- Subcondylar (caudal) area

Frontal view.

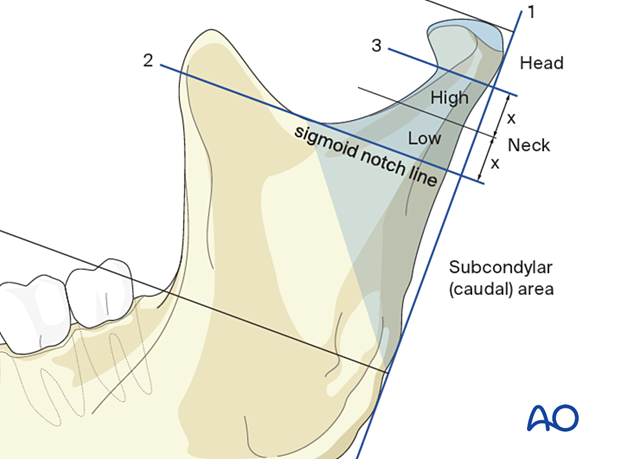

Three lines are used to define these subregions:

- The first line parallels the posterior border of the mandible

- The sigmoid notch line runs perpendicular to the first line at the deepest portion of the sigmoid notch

- The condylar head reference line runs perpendicular to the posterior ramus line below the condylar head's lateral pole. The lateral pole's height is determined by the diameter of a circle, whose arc best fits the lateral pole's upper lateral boundaries.

Clinical pearl: the neck region can be divided into high and low halves by equally dividing the distance between the sigmoid notch line and the lateral pole line.

4. Complete versus incomplete

Complete fractures

Fractures of the mandible in adults are usually complete and entirely interrupt the continuity of the mandibular arch. Such fractures are typically mobile and have various degrees of displacement.

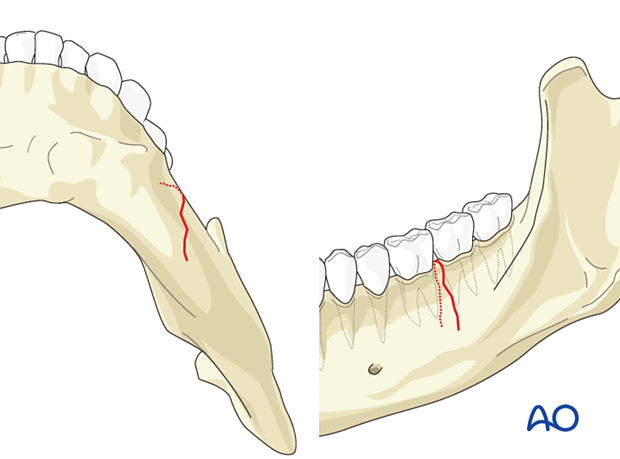

Incomplete fractures

On the other hand, incomplete (greenstick) fractures do not extend through both the buccal and the lingual cortices and the alveolar and basal borders. Incomplete fractures occasionally occur in adults but more often in children. In such cases, the fracture will be nondisplaced and nonmobile. The incomplete fracture might not, therefore, require surgical treatment and may be managed only by a soft diet.

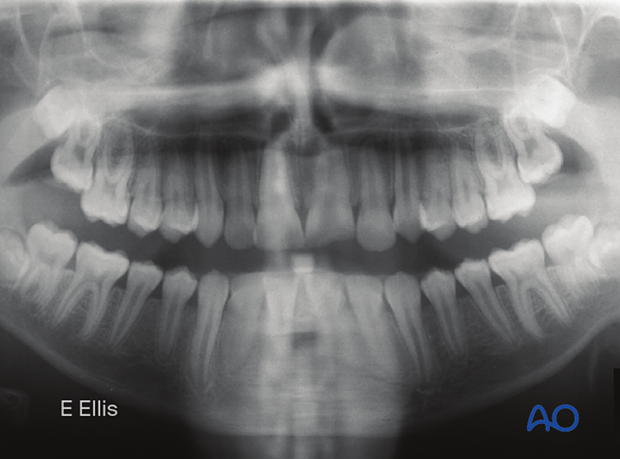

This panoramic X-ray shows an incomplete fracture in the symphysis area.

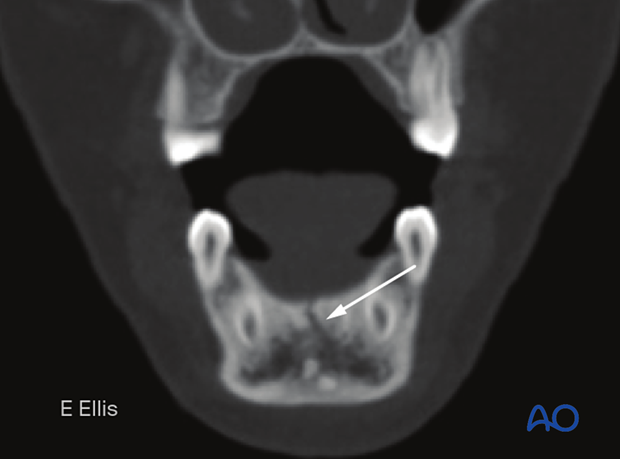

This CT-scan shows an incomplete fracture in a coronal view.

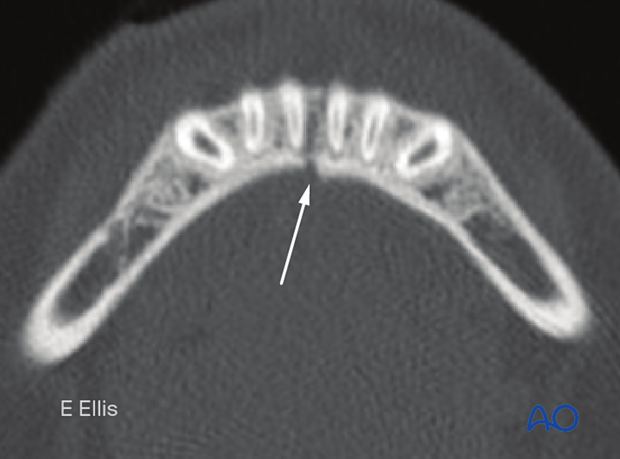

This CT-scan shows an incomplete fracture in the axial view.

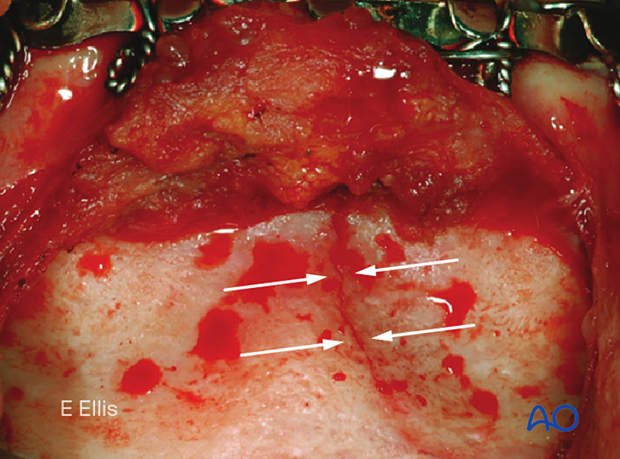

Clinical image of an incomplete fracture. Note the fracture does not extend inferiorly through the basal bone.

5. Fracture morphology

The fracture morphology refers to fragmentation (number of fragments and fracture lines).

Fractures fall into one of two categories:

- Simple or linear

- Complex (multiple lines of fracture)

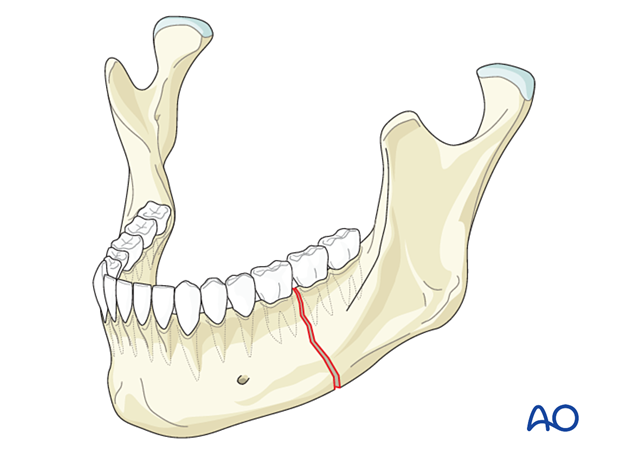

Simple

Simple fractures are linear (one fracture line), resulting in two fragments.

Complex

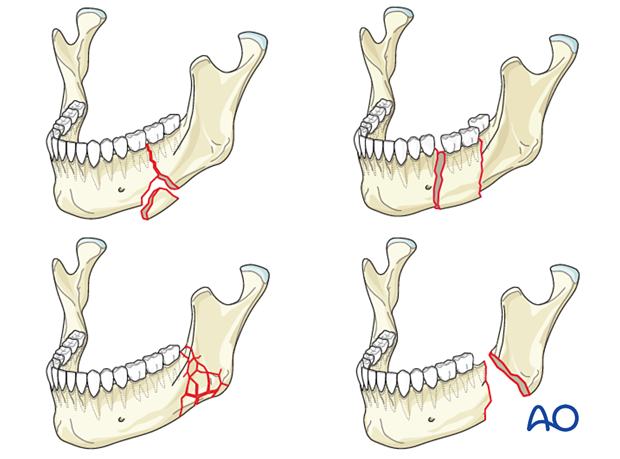

Complex fractures involve at least two fracture lines and three or more fragments in the same region of the mandible. Complex fractures include:

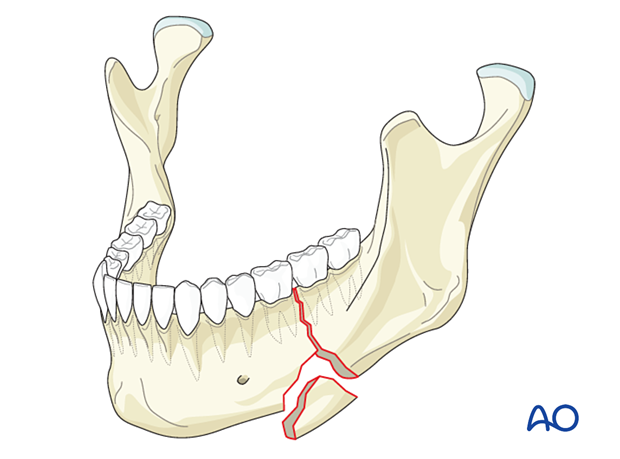

- Basal triangle (wedge) fractures

- Segmental fractures

- Comminuted fractures

- Defect fractures

Simple fractures that are infected or located in an atrophic mandible are also considered complex fractures with regard to treatment.

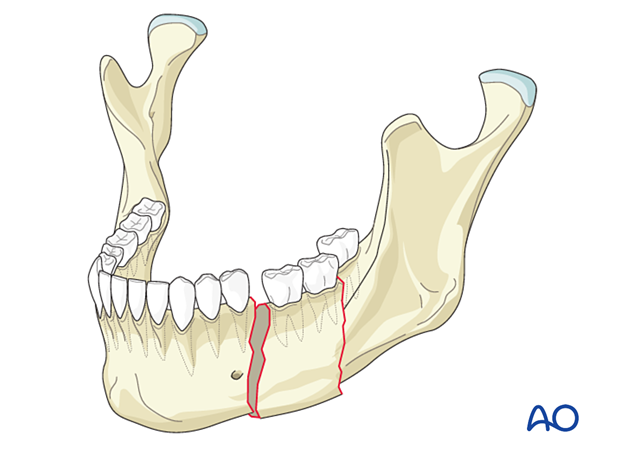

A basal wedge fracture involves a triangle of bone at the inferior border.

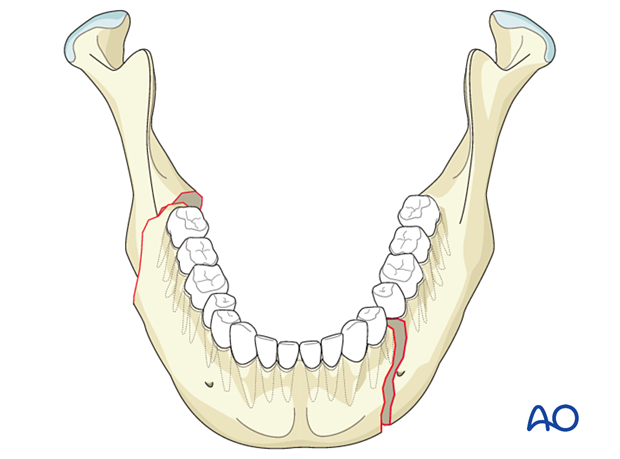

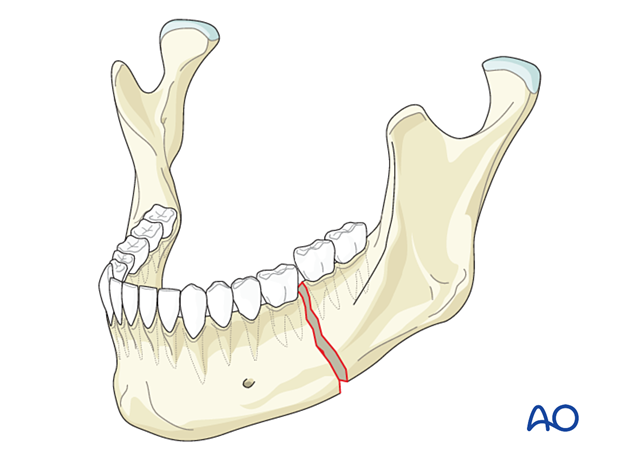

Segmental fractures present two fracture lines, both being complete, within the same anatomic location.

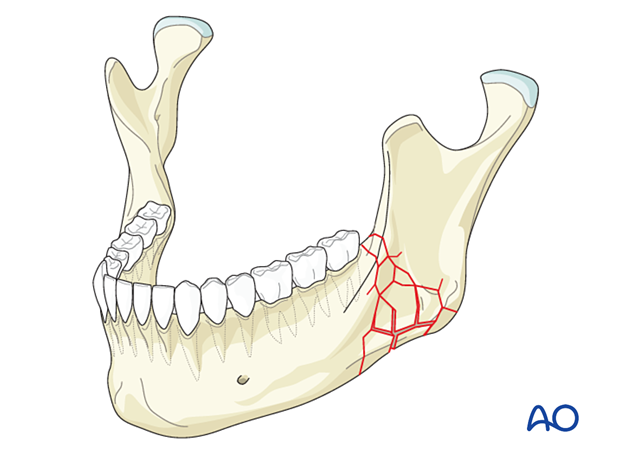

Comminuted fractures involve multiple fracture lines in the same anatomic location resulting in numerous fragments of bone. The bone is often shattered in the fracture area, with fracture lines running in three dimensions.

Many clinicians consider comminuted fractures as synonymous with multifragmentary fractures.

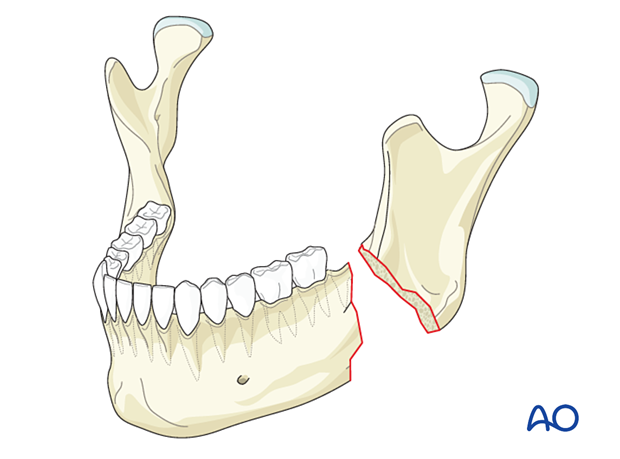

Defect fractures are characterized by a loss of bony structure at the fracture site.

6. Other terms

Open or closed

Intraoral and facial soft tissues adjacent to a fracture can be involved in the injury.

When the fracture site communicates either intraorally through the mucosa or periodontal ligament or extra orally through a laceration or avulsive injury of the overlying skin, the fracture is considered to be open.Therefore all fractures involving the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws are regarded as open fractures.

The terms open fractures, contaminated and compound fractures are synonymous.

Any mandibular fracture that does not have extraoral communication and/or involves the tooth-bearing area is considered a closed fracture (eg, condylar fracture).

Displacement

Fractures can be considered displaced or nondisplaced depending on the relationship of the fracture ends. A fracture is displaced if the fragments are not perfectly anatomically aligned. Displacement is grossly graded as minimal, moderate, or severe. Nevertheless, there is no universally accepted definition for these terms.

The importance of "displacement" is that the more displaced the fracture, the more likely it is to be mobile and contaminated when open.

The terms dislocated, subluxated, and luxated describe the abnormal relationship of the condyle and glenoid fossa's articular surfaces to one another. These terms are synonymous.

Mobile versus nonmobile

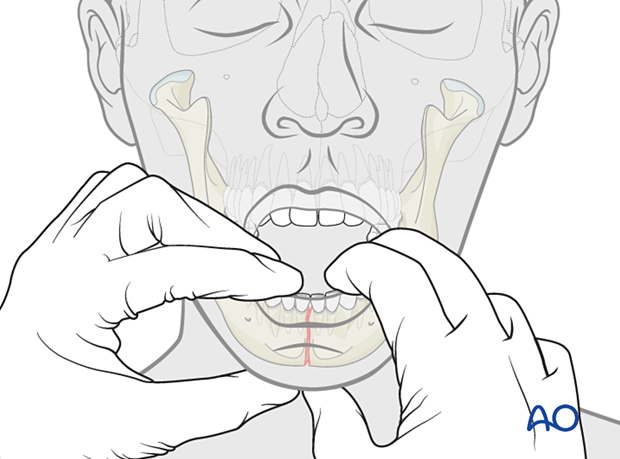

Mobility can be inferred in many cases from the x-rays when there is displacement but is a clinical descriptor that requires the clinician to use both hands, one on either side of the fracture, to feel for mobility.

Mobile fractures are more painful for the patient because any mandible movement such as speaking, eating, or swallowing creates discomfort.