Examination of patients with mandibular fractures

1. Introduction

As with any injury, a thorough assessment requires the following:

- History

- Physical examination

- Radiologic imaging

2. History of the injury

Etiology

The cause of the mandibular fracture is essential because it may indicate fracture type and severity.

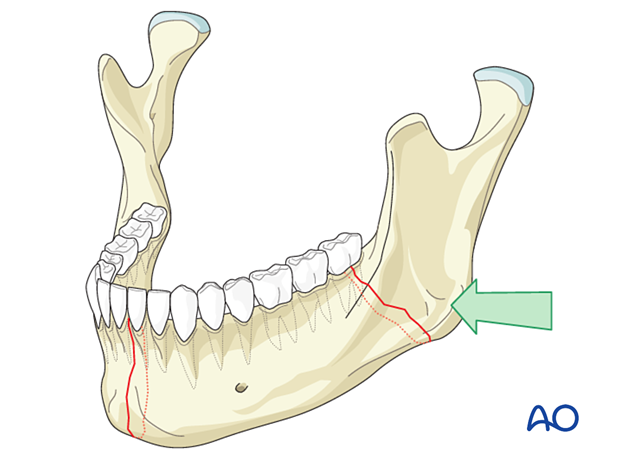

A blow to the mandibular angle will likely cause a fracture of that angle and potentially a contralateral fracture of the body or symphysis.

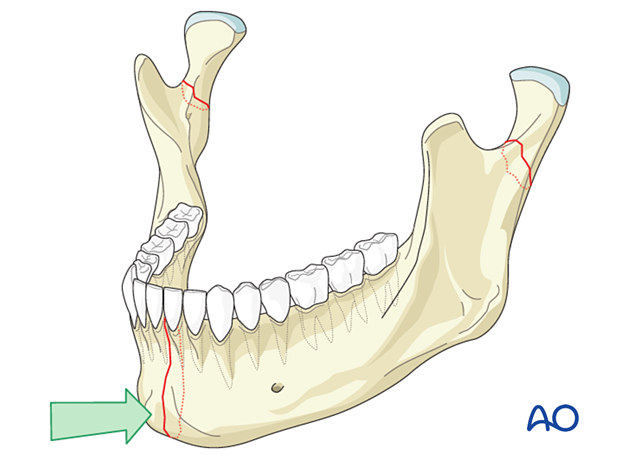

Impact on the chin would lead one to suspect a symphysis or condylar fracture, or both.

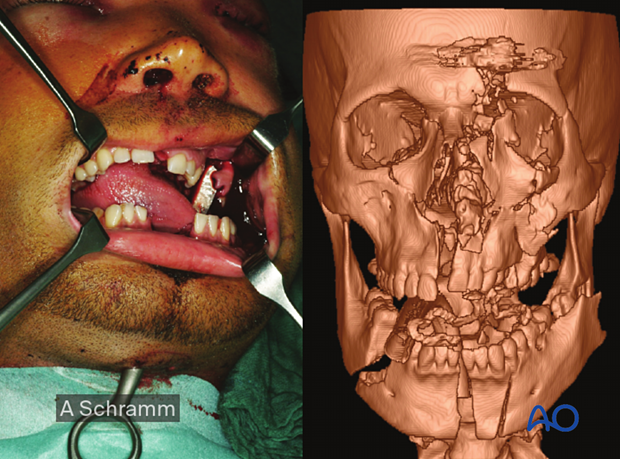

A motor vehicle accident or a gunshot wound would lead one to suspect comminution.

Timelines

The duration between injury and seeking treatment is essential. Studies have shown that the earlier antibiotics can be instituted, the less chance of infections developing in the fracture. A delayed presentation may therefore increase the likelihood of infection.

3. Physical exam

Swelling

The location of swelling will help identify the location of the fracture.

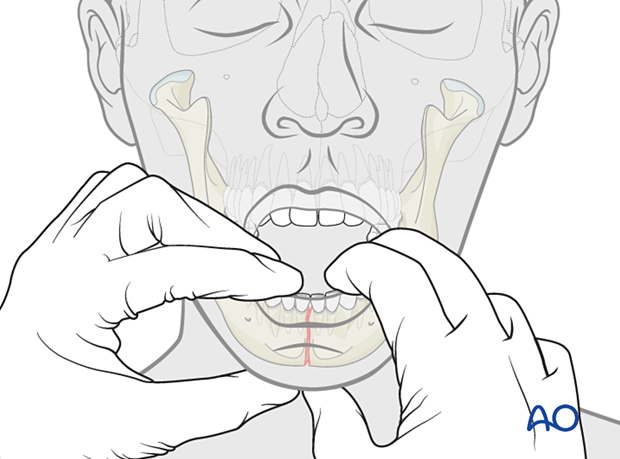

Malocclusion

Malocclusion is one of the most sensitive indicators of mandibular fractures. It may be visible to the clinician and evident to the patient.

The case on the left exhibits an obvious malocclusion caused by a fracture between the left canine and the lateral incisor.

Unilateral hyper occlusion and contralateral open bite usually indicate an ipsilateral condylar fracture.

An anterior open bite usually indicates either bilateral condylar or bilateral angle fractures.

Bilateral crossbite may indicate a combination of symphysis and bilateral condylar fractures.

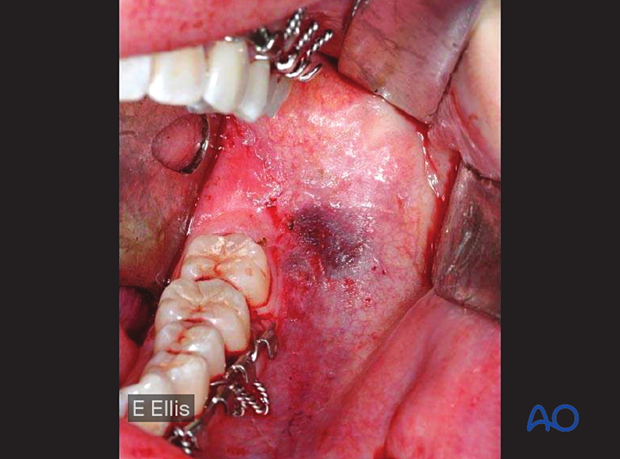

Intraoral hematoma

A sublingual hematoma or other intraoral hematomas may indicate underlying bony fractures.

Intraoral lacerations

Intraoral lacerations of the gingiva will usually indicate an underlying fracture.

Loose teeth

Loose teeth may or may not be associated with bony fractures

Numbness of the mental nerve

Numbness of the mental nerve is a sensitive indicator for a fracture through the mandibular area where the inferior alveolar nerve courses.

Deviation of the mandible on opening

Deviation of the mandible on opening usually indicates a fracture of the mandibular condyle on the deviation side.

Preauricular pain

Preauricular pain may indicate a condylar process fracture or intraarticular hematoma.

Mobility

Mobility across the tooth-bearing regions indicates a fracture.

Keep in mind that any fracture passing through the tooth-bearing area is considered an open (compound) fracture.

4. Radiology

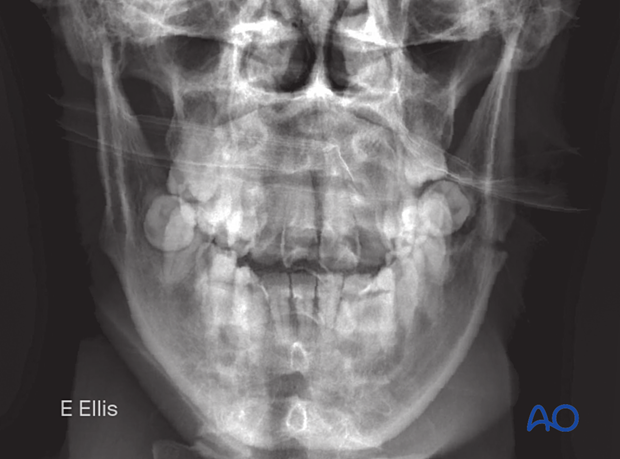

Plain film

Plain films are the least useful but the only imaging available in some cases.

When plain films are used to diagnose mandibular fractures, one should include radiographs taken in two planes at 90° to each other.

The minimum requirement is a PA view and a panoramic view. These views will readily show all fractures of the mandible.

One can supplement these images with:

- a Townes view; to better show the mediolateral position of condylar process fractures.

- Lateral oblique views; to better identify body and angle fractures

a periapical dental film; if there is suspicion of dental root fracture or periapical abscess

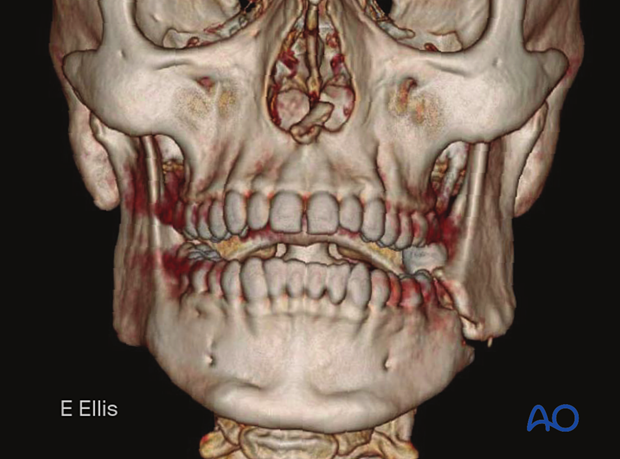

CT and Cone-beam CT

CT or cone-beam CT imaging has become the standard of care for the diagnosis of all facial fractures.

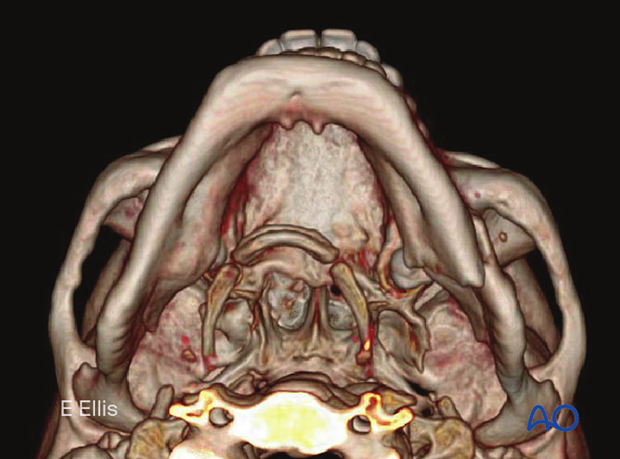

In comminuted fractures, CT and/or cone beam CT is extremely useful for adequate three-dimensional preoperative assessment of the fracture pattern, segmentation, and fragment displacement.

The coronal, sagittal, and axial planes each must be studied.

To have a clear overview, a 3-D image is optimal.