Condylar process and head - simple and complex

Introduction

The mandible is strongest in the midline (symphysis) and weakest at both ends (condyles). One of the most common areas of fracture in the mandible is, therefore, the condylar region.

A blow to the anterior mandibular body is the most common reason for condylar fracture. The force is transmitted from the body of the mandible to the condyle. The condyle is trapped in the glenoid fossa. Commonly, a blow to the ipsilateral mandible causes a contralateral fracture in the condylar region. This design (crumple zone) protects the skull base by preventing displacement of the condyles into the middle cranial fossa following a blow to the symphysis.

If the impact is in the midline of the mandible, fractures of both condylar processes are common.

Unilateral condylar process fractures, simple

Fractures of the condylar process can occur in isolation but are more often combined with other mandibular fractures.

Images

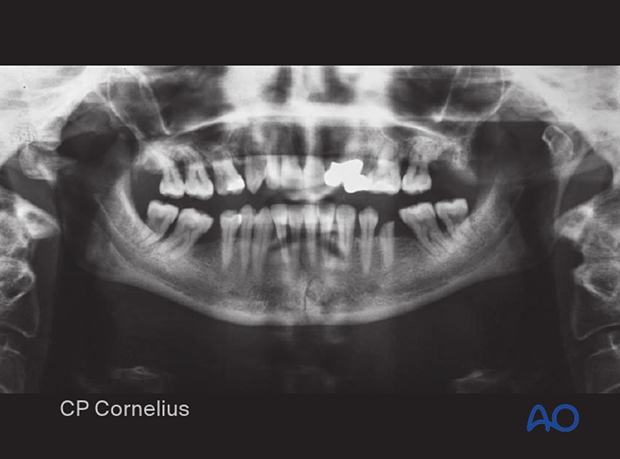

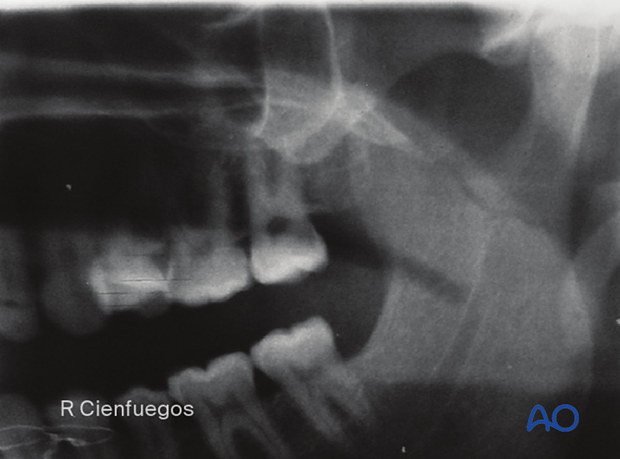

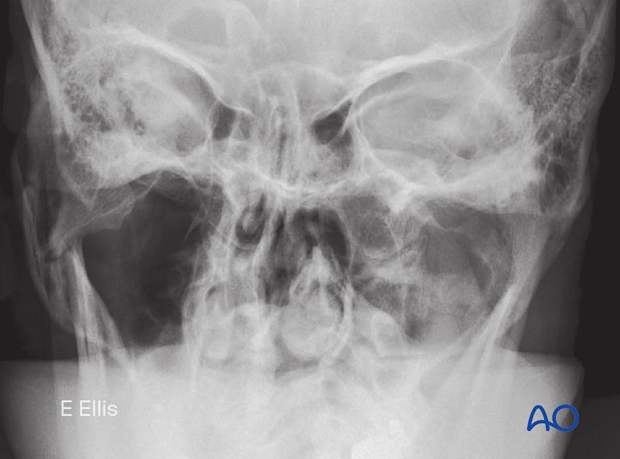

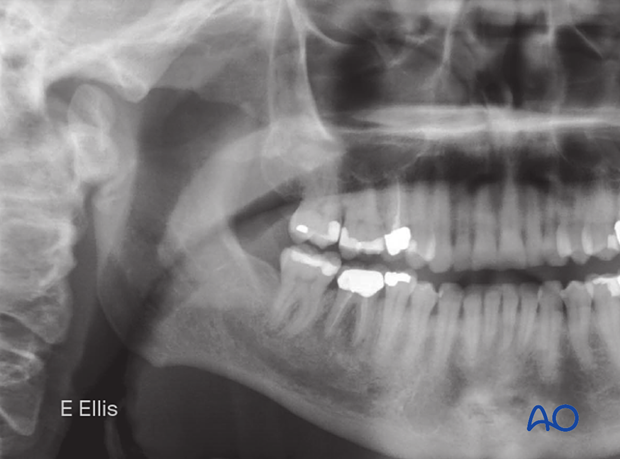

Panoramic view showing left condylar process fracture in association with an anterior body fracture.

CT scans give the best information concerning fracture location, morphology, fragmentation, and associated injuries.

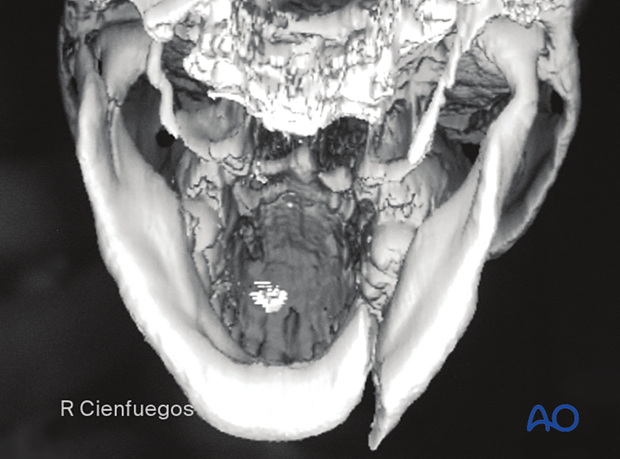

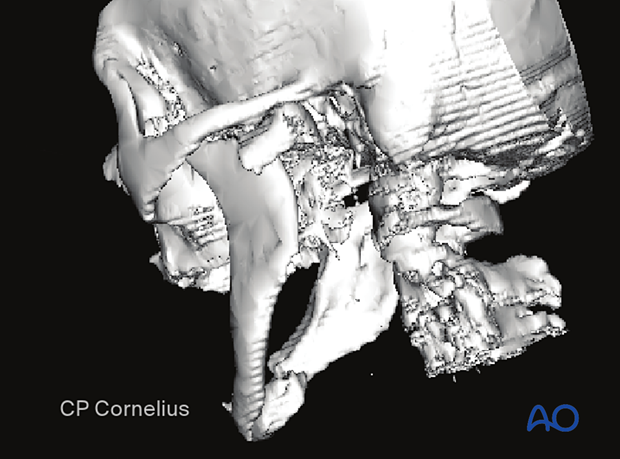

This 3D reconstruction of a CT scan illustrates a right condylar process fracture.

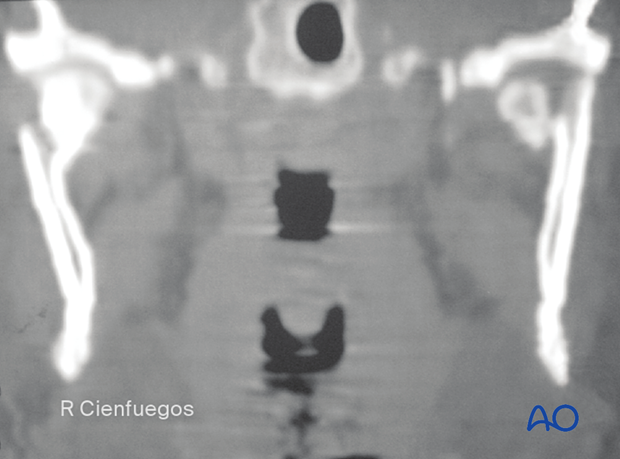

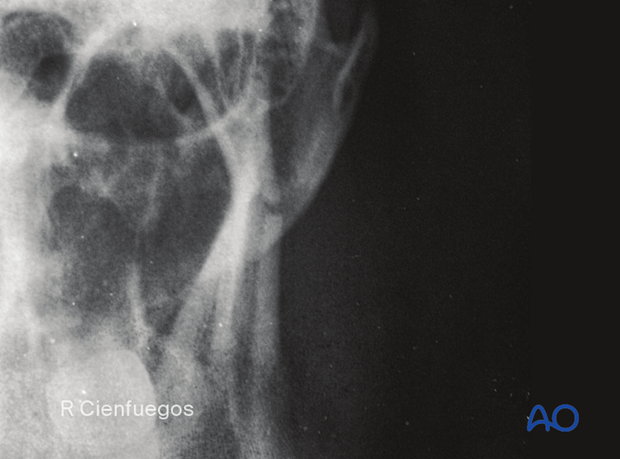

A coronal view of the above patient shows angulation and luxation of the condylar process fracture.

Clinical findings

The dental occlusion can give a clue about the fracture location. With a unilateral condylar process fracture and subsequent height reduction in the ramus region, the clinician will see an ipsilateral premature occlusion and contralateral open bite. The dental midline will shift toward the side of the fracture.

The occlusion shows premature contact on the right side with the deviation of the jaw to the affected side, commonly seen with a right mandibular condyle fracture.

The condylar fragment may be displaced (most often laterally) based on the angulation of the fracture and predominant muscle pull.

Bilateral condylar process fracture

Imaging

CT and/or digital volume tomography (DVT) is extremely useful, especially in high and/or intracapsular fractures of the condyle.

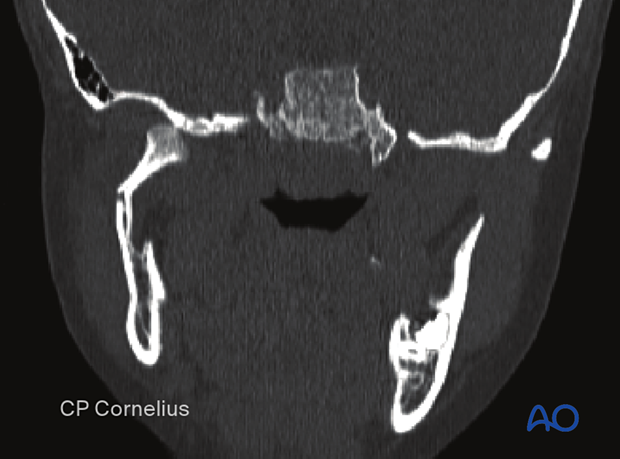

This coronal view demonstrates bilateral condylar process fracture with displacement. There is a condylar neck fracture with angulation on the patient's right side, and on the left side, there is a sagittal condylar head fracture medial to the lateral pole. On the right side, the height of the mandible is not reduced.

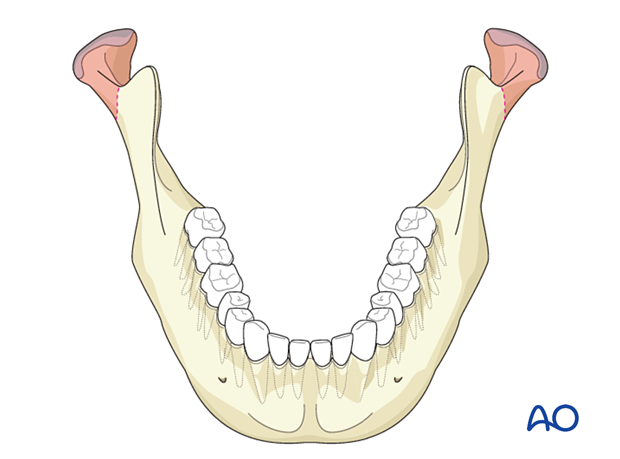

The increased width of the mandible in the ramus/condyle region may indicate an associated fracture in the anterior mandibular arch.

Pitfall: widening of the lower face

Bilateral condyle fractures associated with fractures of the symphysis and body region often widen the mandible and subsequent malocclusion. These fractures are very difficult to treat. Great care must be taken when performing the open reduction and internal fixation of the body fractures to assure the mandible is narrowed to its pre-injury status. Failure to recognize and/or correct the widening of the body fractures will prevent anatomic reduction of the condylar fractures and subsequent occlusal and functional complications.

Clinical findings

Bilateral fractures with shortening and dislocation result in an anterior open bite with minimal deviation of the midline.

Subcondylar fracture

Detail of a panoramic x-ray showing a subcondylar fracture.

Neck fracture

Example of (low) neck fracture

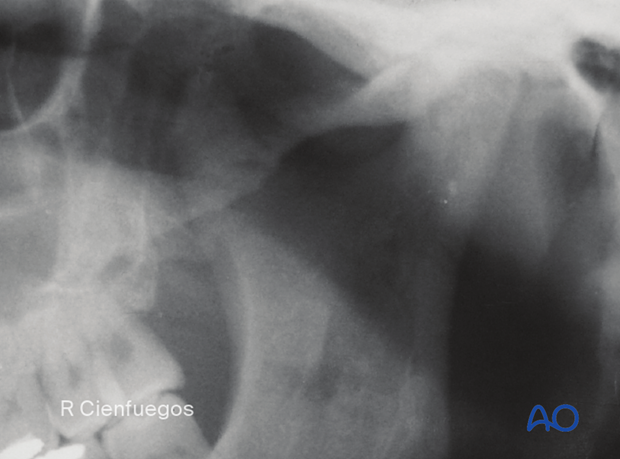

Plain x-ray was taken at 90° to demonstrate displacement of condylar process fracture.

Towne's…

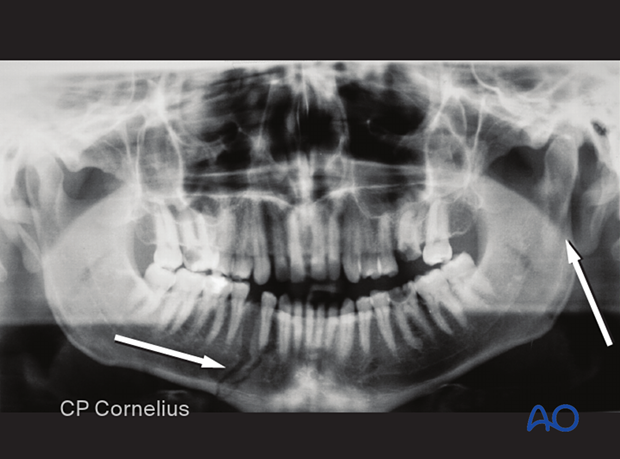

… and panoramic views of a (low) neck fracture.

Example of a (high) neck fracture

3-D reconstructions are useful in identifying fracture height, direction, and severity of displacement.

This 3-D reconstruction illustrates a (high) neck fracture with displacement. Note the associated anterior body fracture of the contralateral side.

Nondisplaced, nondislocated fracture

Nondisplaced, non-dislocated fractures suggest the presence of periosteal support for stability and may not require open treatment.

X-ray in the PA plane shows no vertical shortening.

X-ray shows that no displacement occurred.