The use of existing lacerations

1. Principles

Frequently, patients with facial fractures also have skin lacerations. These existing soft-tissue injuries can often be used to access the facial bones for management of the fractures directly.

The surgeon may elect to extend the laceration to provide adequate access to the fractured area, following the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL).

Bacterial contamination is not a contraindication for the use of existing lacerations for a surgical approach.

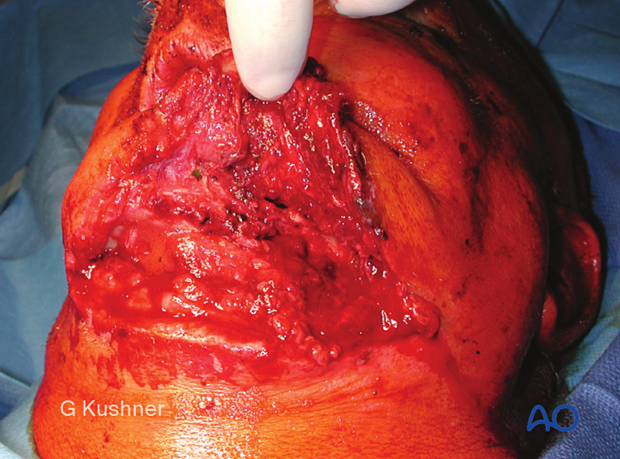

The image shows the initial laceration.

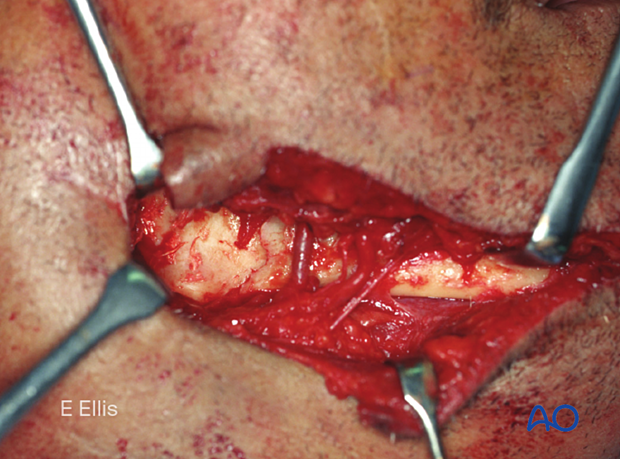

Extended laceration.

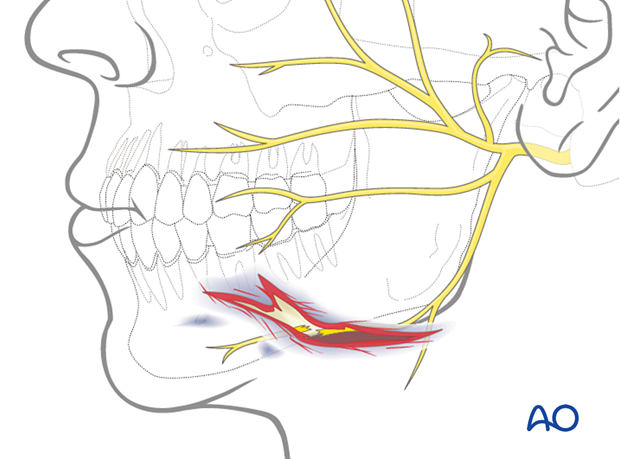

Neurovascular structures

Depending on the location of the laceration, different neurovascular structures may be affected by the injury.

For example, in the illustrated case, the facial nerve is directly involved. The facial nerve can either be repaired primarily or tagged for ease of location during a secondary repair.

One mechanism of finding the distal portion of the lacerated nerve is to use a nerve stimulator. This mechanism will only work in the first few days after the injury. Failure to repair or tag the nerve acutely may make it very difficult to find the nerve later.

It may be advisable to check the nerve for injury before the surgery for medicolegal purposes.

More details on facial nerve repair can be found here.

2. Wound closure

Wound closure for this incision is the primary closure of the laceration. Proper cleansing, debridement, and hemostasis should be accomplished before closure.

The laceration is closed in layers with short-term resorbable interrupted sutures, realigning the anatomic structures and eliminating dead space:

- Periosteum

- Mimetic muscles

- Platysma/SMAS

- Subcutaneous tissues

Injured facial and trigeminal nerve branches are repaired as well as an injured Stensen’s duct.

A variety of skin closure techniques are available based on surgical preference. A drain may be used if necessary.

3. Example of a significant facial laceration with underlying fracture

This image shows an example of soft-tissue laceration.

Elevating the soft-tissue flap reveals the underlying mandibular fracture.