Pediatric general considerations

1. General considerations

Anatomical differences between a child and an adult

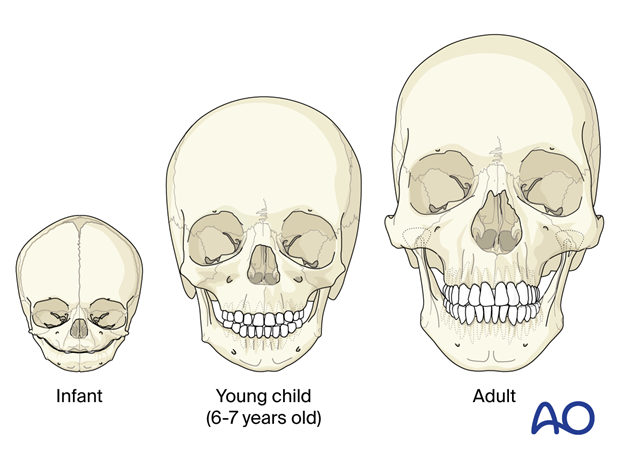

Pediatric anatomy differs from the adult facial anatomy.

Children have a much better blood supply to the face and bones; they heal faster and remodel their bones faster than adults.

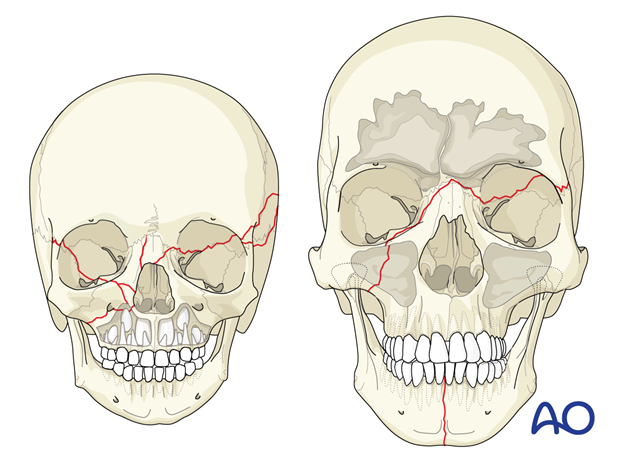

The skull to face proportion is higher in children than in an adult, and therefore children suffer a higher proportion of skull and orbit fractures than adults.

After 12 years, the skull shape is similar to that in adults (apart from the sinus).

Children have a higher ratio of cancellous bone to cortical bone; therefore, most of the fractures are greenstick fractures.

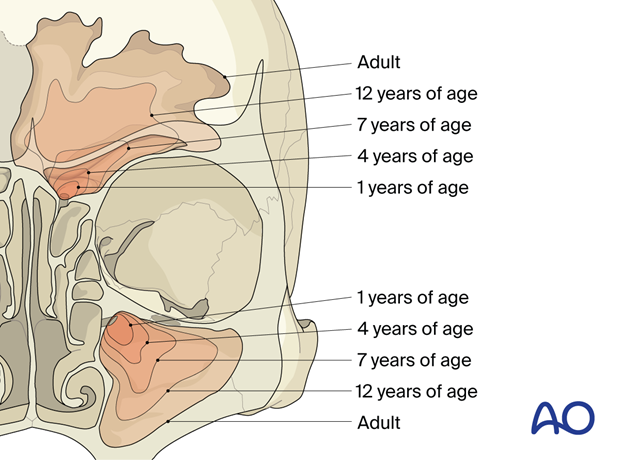

Children under 12 years of age have variable pneumatization of their frontal and maxillary sinuses and therefore do not present with classic fracture patterns.

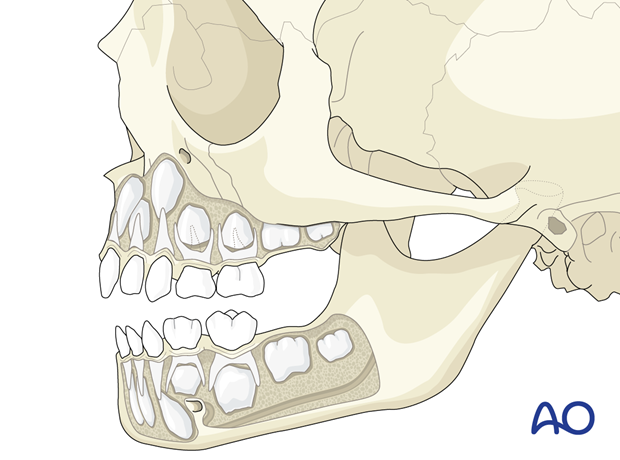

Children under 12 years of age have tooth buds in their maxilla and mandible, which will alter fracture patterns and treatments.

Estimated incidence

Nasal fractures are the most common pediatric fractures seen in the emergency department, followed by mandible fractures, orbital fractures, zygoma fractures, maxillary fractures. NOE fractures are the least common.

Associated injuries

Pediatric facial fractures are commonly associated with other injuries:

- Soft tissue lacerations

- Skull fractures

- Concussions

- CSF leak

- Blinding ocular injury

- Closed chest trauma

- Abdominal trauma

2. Clinical examination

Clinical examination in children is crucial yet can be more complicated than in adults. Children can be uncooperative; functional evaluations such as malocclusion, nerve sensitivity, and vision may be difficult to elicit.

The high incidence of greenstick fractures may render clinical palpation more or less difficult.

Due to the potentially difficult clinical exam, radiographic imaging, such as CT scans, and proper ophthalmological examination are critical for diagnosis.

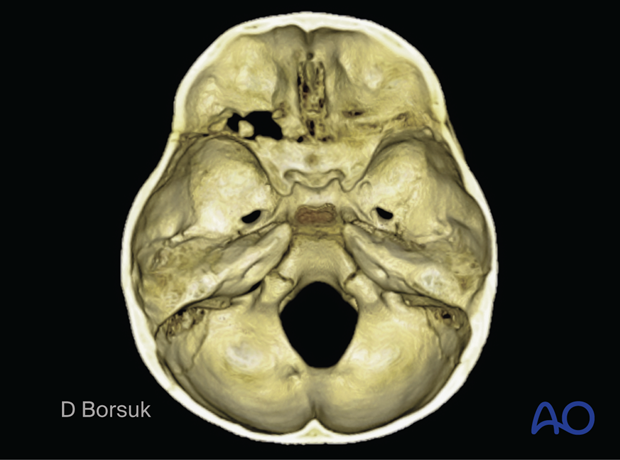

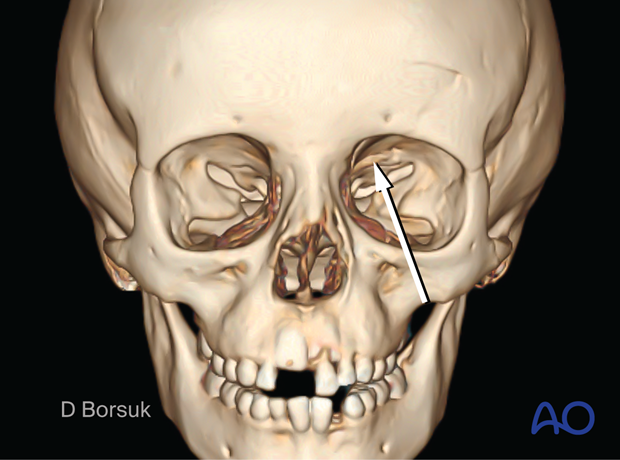

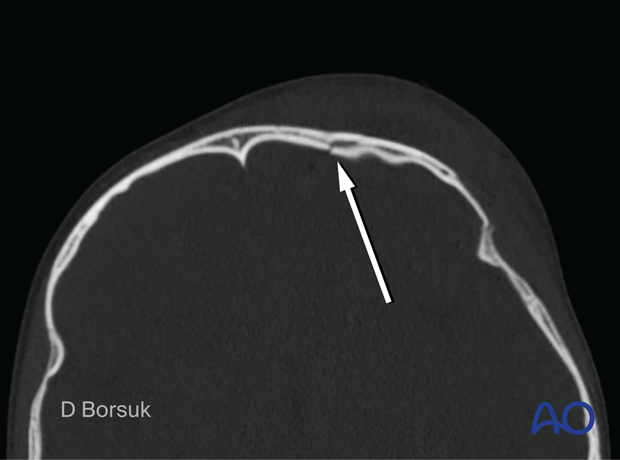

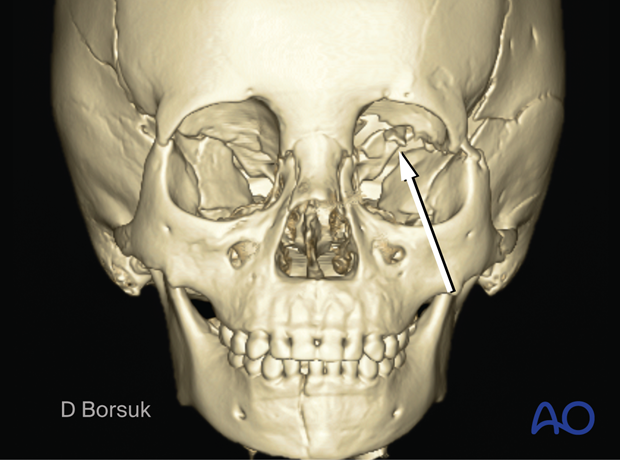

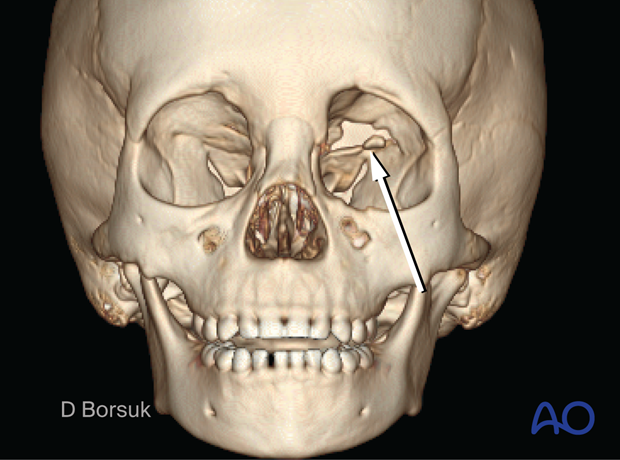

Note the depressed greenstick skull and upper orbit fracture.

Note the absence of the frontal sinus with depressed skull/orbit fracture. This fracture would require short and long-term follow-up to ensure no complications arise, such as a growing skull fracture.

3. CARE approach to pediatric facial fractures

Conservative treatment

Anatomic variation from adults

Relative stability, not rigid

Early follow-up

Conservative treatment

Due to the high incidence of greenstick fractures and the rapid reossification and remodeling, conservative treatment is often the best treatment.

Anatomic variation from adults

Due to the anatomic variation, ie, lack of frontal and maxillary sinuses, higher cancellous to cortical bone ratio, and maxillary tooth buds, classic adult fracture patterns are less commonly observed.

Relative stability, not rigid

Due to the rapid reossification and remodeling, treatment should focus on relative functional stability and not rigid stability. Load bearing fixation is rarely required.

Hardware may need to be removed due to plate migration with growth.

Wide exposure needed for rigid fixation can devascularize and change bone growth potential and should, therefore, be limited to only the most severe fractures.

Early follow up

Due to the increased healing rate, anatomic variations, and potential complications, require early and frequent follow-up is necessary with children.

As an example, growing skull fractures, bone growth disturbance, and tooth bud trauma will only be recognized as the child ages and therefore require continued follow-up.

Case example

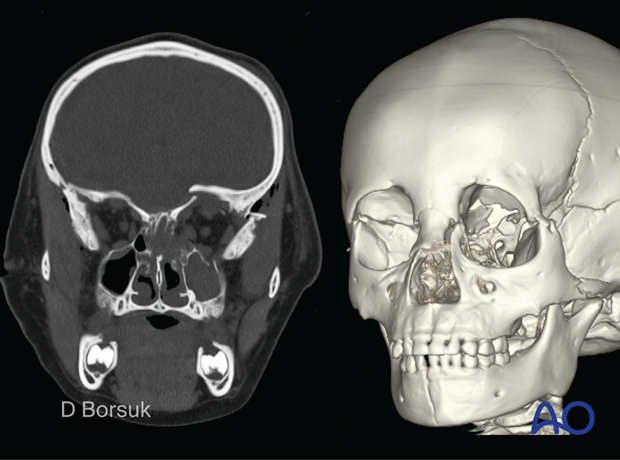

A 4-year-old patient with Le Fort III, skull base, mandible, orbital roof fracture.

Conservative treatment with early and frequent follow-up was chosen.

Six months post-injury displays fracture remodeling of the Le Fort III and mandible fractures.

However, a left orbital roof growing skull fracture was observed through clinical examination (pulsating left globe) and confirmed on a CT scan.

Thanks to early and frequent follow-up, this complication was diagnosed and ultimately treated with titanium alloplastic mesh reconstruction.